There is an apocryphal story about Tolstoy and War and Peace. After receiving the galleys from his publisher, he checked them over, made corrections, and sent them, via courier, back to the publisher. Days later, he was out for a walk, and he cried, “The yacht race! The yacht race!” He had forgotten—as if anything could be forgotten in that encyclopedic novel—a scene that included a yacht race.

There is an apocryphal story about Tolstoy and War and Peace. After receiving the galleys from his publisher, he checked them over, made corrections, and sent them, via courier, back to the publisher. Days later, he was out for a walk, and he cried, “The yacht race! The yacht race!” He had forgotten—as if anything could be forgotten in that encyclopedic novel—a scene that included a yacht race.

Novelists tell each other that story as a means of warning that everything—no matter what—in your mind while you are writing a novel, should go in that novel. Everything. Leave nothing out. Don’t start on another book. Everything now, in this one.

This conception of the novel: book as compendium, the thousand footed beast, as Tom Wolfe called it; has drifted in and out of vogue as writers tried more minimalist work, or work that focused on voice and character as carefully as a short story or novella. Most of my favorite authors: Joyce, Dickens, Marquez, Barth, Chabon; write rampaging maximalist novels that include golems, magnets, dinosaurs, computer-spawned heroes, newspaper headlines, thunderclaps, and the end of the world. It’s easy to think of their novels as rather shaggy, and that is part of their charm, and they wear their shag into the world.

The other side of the spectrum, while still not minimalist, contains James, Faulkner, and Woolf, who delve into the shaggy and unconstructed inner workings of their characters. They are shaggy insofar as they contradict themselves: at one moment feeling free and the next utterly constrained.

All the well. This is incredibly short handed analysis of these writers’ works. But it will have to do. I’m in a hurry.

Right now, and for the past two months, I have been at work on a novel, and I have been scribbling madly at this blog. I’m clearly violating the dictum of “Everything!” I can admit that many of the ideas in these blog posts have emanated from my fiction work. And the other way around. I find the jumping between one form and the other exhilarating and edifying. These non-fiction pieces give me time to puzzle through ideas before they end up in the fiction. Or I can chase down a mad hare that has run out of the novel here in the blog. Of course, sometimes, like when traveling to London, the blog is just a kind of public journal.

To be honest, everything, all of these thoughts, have, in one way or another, ended up in the novel. So far. Even London. Even the ideas about love. Everything. And although there is a story (oh, is there), it is like a snowball rolling down a hillside, picking up branches, mittens, and stray bits of dirt as it careens to the bottom. Even now, this.

Everything.

The charm of London is found in its strange alleyways, endlessly curled streets, and tucked away history. If there is a grid, and in some way, there is, it is bent around the past and the ox bow turns of the Thames, and everything attached to it has been attached in a haphazard fashion. For instance, the coagulation of insurance buildings in central London: the gherkin, the cheese-grater, the scalpel, and the inside-out building; defy any sense of a rational aesthetic plan. Or the juxtaposition of the Tower on one side of the Thames and the glass pineapple of the City Hall just across the river.

The charm of London is found in its strange alleyways, endlessly curled streets, and tucked away history. If there is a grid, and in some way, there is, it is bent around the past and the ox bow turns of the Thames, and everything attached to it has been attached in a haphazard fashion. For instance, the coagulation of insurance buildings in central London: the gherkin, the cheese-grater, the scalpel, and the inside-out building; defy any sense of a rational aesthetic plan. Or the juxtaposition of the Tower on one side of the Thames and the glass pineapple of the City Hall just across the river. And so London’s history is oddly folded into the cityscape as well. A tour through the city—you cannot tour the whole city, or tour it on a bus; you must walk it—folds two thousand years of history, creased around a Roman occupation, a French conquest in 1066, and a fire that destroyed 80% of the city in 1666. And the city is just the square mile that had been walled and gated, but is now open and underlaced with a rail system that carries you quickly to nearly every point beyond the old wall.

And so London’s history is oddly folded into the cityscape as well. A tour through the city—you cannot tour the whole city, or tour it on a bus; you must walk it—folds two thousand years of history, creased around a Roman occupation, a French conquest in 1066, and a fire that destroyed 80% of the city in 1666. And the city is just the square mile that had been walled and gated, but is now open and underlaced with a rail system that carries you quickly to nearly every point beyond the old wall. There is an orderliness to the whole affair. Announcements in the Underground direct people where to walk down hallways and on escalators. Advertisements along the walls of the stations counsel caution with wallets and and advise care with alcohol. “Mind the Gap” is stenciled on the ground where the trains stop, and cheeky announcers corral riders whose fancy Italian made shoes have strayed over the yellow safety line. Cross walks show a green walker when it’s time to cross—around Trafalgar Square the walkers take on a variety of LGBT friendly forms: couples and symbols. Just remember to cross when the green light comes!

There is an orderliness to the whole affair. Announcements in the Underground direct people where to walk down hallways and on escalators. Advertisements along the walls of the stations counsel caution with wallets and and advise care with alcohol. “Mind the Gap” is stenciled on the ground where the trains stop, and cheeky announcers corral riders whose fancy Italian made shoes have strayed over the yellow safety line. Cross walks show a green walker when it’s time to cross—around Trafalgar Square the walkers take on a variety of LGBT friendly forms: couples and symbols. Just remember to cross when the green light comes! History is a story of discontinuous events—events that collide like weather systems or galaxies, having barely understood origins, and even less decipherable records. All the witnesses were destroyed in the collision. What they saw, what they thought, and what they felt—even if they recorded their observations on stone, paper, steel, or silicone, have been destroyed along with them. We are living in the age of delusion, in which we believe in the sanctity of our recorded history—either self-scribbled or captured by another.

History is a story of discontinuous events—events that collide like weather systems or galaxies, having barely understood origins, and even less decipherable records. All the witnesses were destroyed in the collision. What they saw, what they thought, and what they felt—even if they recorded their observations on stone, paper, steel, or silicone, have been destroyed along with them. We are living in the age of delusion, in which we believe in the sanctity of our recorded history—either self-scribbled or captured by another. Second, in the musical Hamilton (which was also part of this trip to London), the character of George Washington warns Hamilton that we do not control who writes our stories. He’s telling this to a man who believes in his power to literally write his own story—and to use his words to cement his reality. He can’t—and doesn’t. His wife, Eliza, sends his legacy forward—and Lin Manuel Miranda brings us her legacy. But, as Miranda admits in interviews, even this moment for Hamilton—and therefore, for him as well—is provisional and subject to changing tastes and critical opinion.

Second, in the musical Hamilton (which was also part of this trip to London), the character of George Washington warns Hamilton that we do not control who writes our stories. He’s telling this to a man who believes in his power to literally write his own story—and to use his words to cement his reality. He can’t—and doesn’t. His wife, Eliza, sends his legacy forward—and Lin Manuel Miranda brings us her legacy. But, as Miranda admits in interviews, even this moment for Hamilton—and therefore, for him as well—is provisional and subject to changing tastes and critical opinion. I had always shrugged off the idea of traveling to the Grand Canyon. I was one of those, “what’s the big deal about a big hole in the ground” skeptics. I was wrong. Of course I was wrong. The Grand Canyon is an amazement—and of course, I was properly amazed when I saw it—looking into two billion years of rock will do that, should do that. I realized that what I had held aside was not the geology or the landscape, but the travel. Why had I discounted my ability to be amazed by travel? I had done it all my life. Going, all kinds of going, even if so much of it has been more local—on this continent, in this country—has been part of me all my life.

I had always shrugged off the idea of traveling to the Grand Canyon. I was one of those, “what’s the big deal about a big hole in the ground” skeptics. I was wrong. Of course I was wrong. The Grand Canyon is an amazement—and of course, I was properly amazed when I saw it—looking into two billion years of rock will do that, should do that. I realized that what I had held aside was not the geology or the landscape, but the travel. Why had I discounted my ability to be amazed by travel? I had done it all my life. Going, all kinds of going, even if so much of it has been more local—on this continent, in this country—has been part of me all my life. I loved airplanes and airports. Departures were invitations to new adventures. When I traveled with my family, I usually sat alone—the hazard or benefit of being an odd numbered group. I took my first plane flight alone when I went to Iowa to swim; I was 15. I traveled by train and bus alone all through my early adult life. I usually traveled to visit friends. However, I also went to cities to simply see them, to look at buildings, and camp in museums—visiting and revisiting works of art that held sway over my imagination.

I loved airplanes and airports. Departures were invitations to new adventures. When I traveled with my family, I usually sat alone—the hazard or benefit of being an odd numbered group. I took my first plane flight alone when I went to Iowa to swim; I was 15. I traveled by train and bus alone all through my early adult life. I usually traveled to visit friends. However, I also went to cities to simply see them, to look at buildings, and camp in museums—visiting and revisiting works of art that held sway over my imagination. There were trips under sail with my father and brothers. These were tests as well as trips. The ocean makes us foreign to ourselves, our bodies not made to be perpetually wet, and perpetually in motion—shaken and stirred. I have never been anywhere larger than surrounded by sky and ocean, never felt as alive, nor as alone.

There were trips under sail with my father and brothers. These were tests as well as trips. The ocean makes us foreign to ourselves, our bodies not made to be perpetually wet, and perpetually in motion—shaken and stirred. I have never been anywhere larger than surrounded by sky and ocean, never felt as alive, nor as alone. A current meme on Facebook compares what Moms used to say to their kids with what they say now. It is held up as a clarion call to the virtues of yesteryear, when Moms—and their kids—knew what was what. Over and over again, stuff (stuff) like this careens around the internet, in casual banter on news shows, in conversations in my workplaces. Those of us who grew up in the mythical “then” look back with nostalgia, and look at this moment with a jocular disdain. I would like to call “bullshit” on the whole enterprise.

A current meme on Facebook compares what Moms used to say to their kids with what they say now. It is held up as a clarion call to the virtues of yesteryear, when Moms—and their kids—knew what was what. Over and over again, stuff (stuff) like this careens around the internet, in casual banter on news shows, in conversations in my workplaces. Those of us who grew up in the mythical “then” look back with nostalgia, and look at this moment with a jocular disdain. I would like to call “bullshit” on the whole enterprise. My mother did what she thought and felt was right. She learned her lessons from her mother and family—and what lessons they were. Some things, she changed. She never leashed us to trees in the front yard. Others were more indelible. I am certain that most of us parent in the same way—sifting through the conscious and unconscious lessons that we received from our parents. What we do, we do almost on a kind of autopilot—in the heat of the moment, dumb memory takes over. Change is hard.

My mother did what she thought and felt was right. She learned her lessons from her mother and family—and what lessons they were. Some things, she changed. She never leashed us to trees in the front yard. Others were more indelible. I am certain that most of us parent in the same way—sifting through the conscious and unconscious lessons that we received from our parents. What we do, we do almost on a kind of autopilot—in the heat of the moment, dumb memory takes over. Change is hard. So much of wit is based on shared experiences. I know I can toss in a “Brian Clements, we love you, get up!” to my friend Brian, and he will smile that wry smile that accompanies a reference to O’Hara. Or proclaim, “Hell, I love everybody!” and he will know what I mean. If I draw my finger across my eye, we have traveled into Bunuel’s fractured mindscape. We share those images and words. I can tell my brother to “Blanket the fucking jib,” and he will know the context. My mother can call me a “Son of a Bitch,” and know the ground upon which she treads. My father would offer a “You have all done very well,” recognizing the provenance of ignorance that surrounded Mr. Grace’s signature line.

So much of wit is based on shared experiences. I know I can toss in a “Brian Clements, we love you, get up!” to my friend Brian, and he will smile that wry smile that accompanies a reference to O’Hara. Or proclaim, “Hell, I love everybody!” and he will know what I mean. If I draw my finger across my eye, we have traveled into Bunuel’s fractured mindscape. We share those images and words. I can tell my brother to “Blanket the fucking jib,” and he will know the context. My mother can call me a “Son of a Bitch,” and know the ground upon which she treads. My father would offer a “You have all done very well,” recognizing the provenance of ignorance that surrounded Mr. Grace’s signature line.

At some point—and it happens fairly quickly—the life of an English teacher becomes more about re-reading than reading. This is a preposterous change from the life of a graduate student, when everything is reading. As a student, there may be a handful of books that one reads a twice, but those are also the books with which one spends an engaged period of time—there is an essay in the offing. If you read them twice, chances are you read them a half dozen or dozen times. By the time you start teaching, the repetition is no longer driven by your desire or directed curiosity, but by a curricular roadmap that more often than not, you have not decided.

At some point—and it happens fairly quickly—the life of an English teacher becomes more about re-reading than reading. This is a preposterous change from the life of a graduate student, when everything is reading. As a student, there may be a handful of books that one reads a twice, but those are also the books with which one spends an engaged period of time—there is an essay in the offing. If you read them twice, chances are you read them a half dozen or dozen times. By the time you start teaching, the repetition is no longer driven by your desire or directed curiosity, but by a curricular roadmap that more often than not, you have not decided. I feel the loss keenly. I am dissatisfied with the too morbid outcomes that serious writers propose, and with the deathly insistence on disconnection and disappointment. And I am dissatisfied with trudging over this same ground over and over again. There must be the possibility of joy, and please, for gods’ sakes, there must be discovery. Which means new works. In “Seymour: An Introduction,” Salinger allows Seymour to give his brother, Bruno, the single best piece of writing advice—and by extension, life advice—I have ever read. It is hopeful. “Imagine the book you most want to read… Now write it.”

I feel the loss keenly. I am dissatisfied with the too morbid outcomes that serious writers propose, and with the deathly insistence on disconnection and disappointment. And I am dissatisfied with trudging over this same ground over and over again. There must be the possibility of joy, and please, for gods’ sakes, there must be discovery. Which means new works. In “Seymour: An Introduction,” Salinger allows Seymour to give his brother, Bruno, the single best piece of writing advice—and by extension, life advice—I have ever read. It is hopeful. “Imagine the book you most want to read… Now write it.”

When I sit down to write, I haven’t thought about an audience. Often I feel more like an amanuensis, copying down whatever the universe commands. The universe commands much, by the way. You might call it inspiration—divine or otherwise. I have not spent much time trying to figure out “my voice,” as much as I have trying to listen keenly to what comes my way.

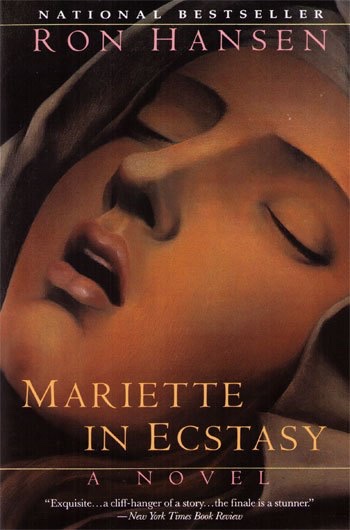

When I sit down to write, I haven’t thought about an audience. Often I feel more like an amanuensis, copying down whatever the universe commands. The universe commands much, by the way. You might call it inspiration—divine or otherwise. I have not spent much time trying to figure out “my voice,” as much as I have trying to listen keenly to what comes my way. One of my first teachers, Ron Hansen, ends his spectacular novel Mariette in Ecstasy with Mariette’s message from her muse (who just happens to be God). The message is, “Surprise me.” I read that years and years ago, and only now has the lesson begun to take hold. How I wish I had stumbled into that realization 20 years ago. But better now, late as it is, than not at all.

One of my first teachers, Ron Hansen, ends his spectacular novel Mariette in Ecstasy with Mariette’s message from her muse (who just happens to be God). The message is, “Surprise me.” I read that years and years ago, and only now has the lesson begun to take hold. How I wish I had stumbled into that realization 20 years ago. But better now, late as it is, than not at all.