Some of my students are aghast at the idea of reading a book a second time, let alone a third or forth, or fifteenth time. The life of a teacher means revisiting books again and again. They become habits. The past dozen years brought steady stops in S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders and Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, Homer’s Odyssey, and maybe Shakespeare’s Macbeth. All became exceedingly familiar territory—terra too cognito—and I welcomed the changes that a change of job and change of curriculum brought this year. I taught half a dozen book I had not read in years. The freshness helped revive my vision.

Of course, repetition is the backbone of study. There isn’t a piece, whether film, book, or painting, that I have not poured over. And over. Some works hold up to repeated visits—this is especially of true of paintings and sculptures. I have sat in front of some paintings for hours, and then gone back a year later to do more. The ability to give concentrated attention to something is a rare quality. And yet, I find myself loosing the fire for return visits and viewings, even for old favorites. How many times can I return to Hamlet, or It’s a Wonderful Life, or Wings of Desire? I know there are things I have not seen, and they call to me.

With spring, my attention is pulled back to baseball, and a group of friends with whom I have played rotisserie baseball for nearly thirty years. I have risen at odd hours when the season began in Japan, as it did again this season. I did not wake to watch early in the morning, but acknowledged the game at arm’s length. I almost did not play our little game this season, almost tired of keeping track of scores and statistics. 162 games and fifteen teams works out to nearly 2500 events to be aware of in some nagging fashion. Enough already.

How much has repetition and routine play a part in life? Too much. At times it seemed that I flew on autopilot, barely aware of the ground beneath me or the time that slipped past, never to return. Sometimes the routine is good—I don’t give more than passing thought to breakfast and lunch when I am busy. I eat the same thing, more or less, day after day. Perhaps my life would be better if I added variations here, but I have had other pressing concerns, like a Stephen Greenblatt essay about Hamlet. There are ways to keep the standards fresh. Still, there must be more.

I changed large parts of my life this past year—there were many reasons, but one was to interrupt the flow that had become too familiar, too easy. I wanted to drive up to a different door—my door. It did not have to be more beautiful—and it wasn’t—it just had to be different. My work as a teacher, although familiar enough, had to take me to different books an different students. And I needed to extricate myself from a years long creative drought. I needed to write to be alive.

This past December, I traveled to a new place, London, to which I had meant to travel almost thirty years ago. I traveled after I did a series of new things, each one satisfying, but each fueling a desire for more. Almost everything that has been part of the solid ritual of my daily routine tastes bland. I don’t hanker for extremes—a solo sailing venture around the world, or an ascent up some foreboding mountain, or a year in a seraglio—I yearn to encounter something as if for the first time. I wish to be a beginner again, with a clean slate ahead of me.

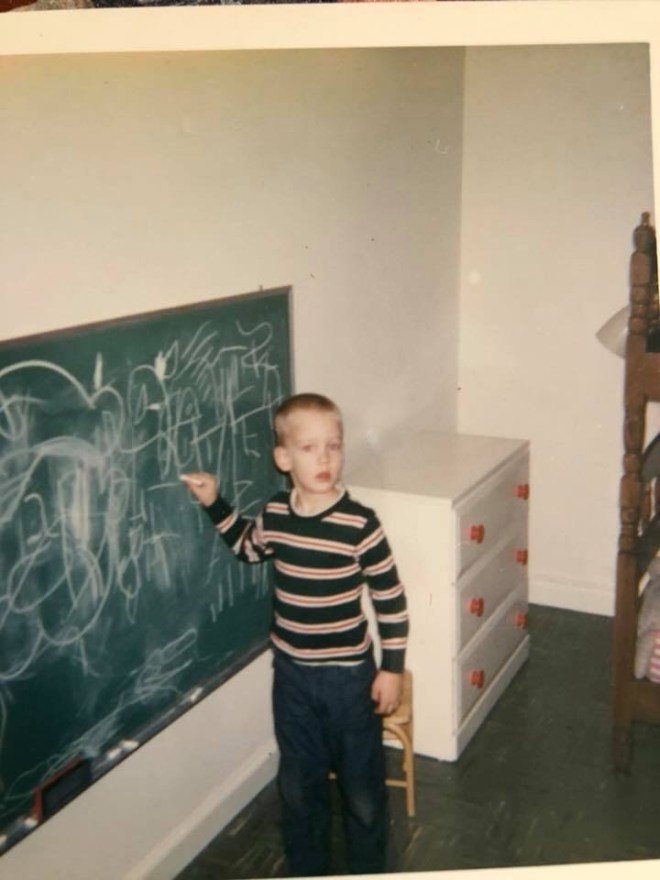

This past December, I traveled to a new place, London, to which I had meant to travel almost thirty years ago. I traveled after I did a series of new things, each one satisfying, but each fueling a desire for more. Almost everything that has been part of the solid ritual of my daily routine tastes bland. I don’t hanker for extremes—a solo sailing venture around the world, or an ascent up some foreboding mountain, or a year in a seraglio—I yearn to encounter something as if for the first time. I wish to be a beginner again, with a clean slate ahead of me.

It will not be. There is much that I cannot jettison (Overboard! Overboard!), and some of which has been central to my life. But to bring my daughter along for the ride. To carry my brave and loving heart into boundless possibility. To write without care for sharp tongued critique. To go, and keep going.

I recognize that when I felt at my best, I was a student, learning, reading, discovering with a vigor that few matched. Right now my writing carries me vigorously to some new place—an undiscovered country that is beyond death—the little death of stagnation and routine, the larger death of a withered soul. I need to find a way to return this more adventurous, more daring, more profound sense of discovery to the rest of my life, to every aspect of my life. To become a masterful student again. Even while I wear the mantle of expert, I am an expert explorer. It is time to honor that. And go.

Perhaps my writing will be enough to answer that call during the long school year. My work feels, for the first time in longer than I care to admit, durable and ecstatic. However, I cannot let anything—or anyone, even myself—keep me from discovery. There must be time for new thoughts, new places, and a new world that will animate my work and revive my old heart. Here—there, and everywhere—I go.

I have been struggling with masculinity as of late. Which is to say, struggling with ambition. Or struggling with my career choices. Or struggling with relationship choices. Or, simply struggling. Because I am a man, I am struggling on the somewhat closed field of masculinity. I haven’t always thought of it that way, and yet, there it is. I have avoided masculinity for dozens of reasons.

I have been struggling with masculinity as of late. Which is to say, struggling with ambition. Or struggling with my career choices. Or struggling with relationship choices. Or, simply struggling. Because I am a man, I am struggling on the somewhat closed field of masculinity. I haven’t always thought of it that way, and yet, there it is. I have avoided masculinity for dozens of reasons. History is a story of discontinuous events—events that collide like weather systems or galaxies, having barely understood origins, and even less decipherable records. All the witnesses were destroyed in the collision. What they saw, what they thought, and what they felt—even if they recorded their observations on stone, paper, steel, or silicone, have been destroyed along with them. We are living in the age of delusion, in which we believe in the sanctity of our recorded history—either self-scribbled or captured by another.

History is a story of discontinuous events—events that collide like weather systems or galaxies, having barely understood origins, and even less decipherable records. All the witnesses were destroyed in the collision. What they saw, what they thought, and what they felt—even if they recorded their observations on stone, paper, steel, or silicone, have been destroyed along with them. We are living in the age of delusion, in which we believe in the sanctity of our recorded history—either self-scribbled or captured by another. Second, in the musical Hamilton (which was also part of this trip to London), the character of George Washington warns Hamilton that we do not control who writes our stories. He’s telling this to a man who believes in his power to literally write his own story—and to use his words to cement his reality. He can’t—and doesn’t. His wife, Eliza, sends his legacy forward—and Lin Manuel Miranda brings us her legacy. But, as Miranda admits in interviews, even this moment for Hamilton—and therefore, for him as well—is provisional and subject to changing tastes and critical opinion.

Second, in the musical Hamilton (which was also part of this trip to London), the character of George Washington warns Hamilton that we do not control who writes our stories. He’s telling this to a man who believes in his power to literally write his own story—and to use his words to cement his reality. He can’t—and doesn’t. His wife, Eliza, sends his legacy forward—and Lin Manuel Miranda brings us her legacy. But, as Miranda admits in interviews, even this moment for Hamilton—and therefore, for him as well—is provisional and subject to changing tastes and critical opinion. A current meme on Facebook compares what Moms used to say to their kids with what they say now. It is held up as a clarion call to the virtues of yesteryear, when Moms—and their kids—knew what was what. Over and over again, stuff (stuff) like this careens around the internet, in casual banter on news shows, in conversations in my workplaces. Those of us who grew up in the mythical “then” look back with nostalgia, and look at this moment with a jocular disdain. I would like to call “bullshit” on the whole enterprise.

A current meme on Facebook compares what Moms used to say to their kids with what they say now. It is held up as a clarion call to the virtues of yesteryear, when Moms—and their kids—knew what was what. Over and over again, stuff (stuff) like this careens around the internet, in casual banter on news shows, in conversations in my workplaces. Those of us who grew up in the mythical “then” look back with nostalgia, and look at this moment with a jocular disdain. I would like to call “bullshit” on the whole enterprise. My mother did what she thought and felt was right. She learned her lessons from her mother and family—and what lessons they were. Some things, she changed. She never leashed us to trees in the front yard. Others were more indelible. I am certain that most of us parent in the same way—sifting through the conscious and unconscious lessons that we received from our parents. What we do, we do almost on a kind of autopilot—in the heat of the moment, dumb memory takes over. Change is hard.

My mother did what she thought and felt was right. She learned her lessons from her mother and family—and what lessons they were. Some things, she changed. She never leashed us to trees in the front yard. Others were more indelible. I am certain that most of us parent in the same way—sifting through the conscious and unconscious lessons that we received from our parents. What we do, we do almost on a kind of autopilot—in the heat of the moment, dumb memory takes over. Change is hard. So much of wit is based on shared experiences. I know I can toss in a “Brian Clements, we love you, get up!” to my friend Brian, and he will smile that wry smile that accompanies a reference to O’Hara. Or proclaim, “Hell, I love everybody!” and he will know what I mean. If I draw my finger across my eye, we have traveled into Bunuel’s fractured mindscape. We share those images and words. I can tell my brother to “Blanket the fucking jib,” and he will know the context. My mother can call me a “Son of a Bitch,” and know the ground upon which she treads. My father would offer a “You have all done very well,” recognizing the provenance of ignorance that surrounded Mr. Grace’s signature line.

So much of wit is based on shared experiences. I know I can toss in a “Brian Clements, we love you, get up!” to my friend Brian, and he will smile that wry smile that accompanies a reference to O’Hara. Or proclaim, “Hell, I love everybody!” and he will know what I mean. If I draw my finger across my eye, we have traveled into Bunuel’s fractured mindscape. We share those images and words. I can tell my brother to “Blanket the fucking jib,” and he will know the context. My mother can call me a “Son of a Bitch,” and know the ground upon which she treads. My father would offer a “You have all done very well,” recognizing the provenance of ignorance that surrounded Mr. Grace’s signature line. In many ways, I take solace in being surrounded by memories, and there are some that I purposefully mine. The routine of the same lunch—on most days—reminds me of years of similar lunches from the time I was five—earlier—until just last week—and all the lunches in between. I feel comforted by the way those memories permeate my present so easily.

In many ways, I take solace in being surrounded by memories, and there are some that I purposefully mine. The routine of the same lunch—on most days—reminds me of years of similar lunches from the time I was five—earlier—until just last week—and all the lunches in between. I feel comforted by the way those memories permeate my present so easily. I have written about the powerful memories associated with places—a rolling set of hills on a road headed north, an intersection with two right turn lanes, a road sign, the curve of a shoreline, a buoy. But, it is everything else as well. All the things. My walls at home are lined with books, and the books speak—not just of what is contained in their pages, but of the times I read them, the places I was, the company that surrounded those moments. And there is more, a gesture, my hand on a doorknob, the sudden turn of my head when I look for something, the way my foot falls on a stair. I am out of myself in a flash, or at least out of this time—even though I know that I am inextricably in it—and another older time surges through me. Even when still, this heartbeat explodes into a thousand, a million other heartbeats, and time collapses.

I have written about the powerful memories associated with places—a rolling set of hills on a road headed north, an intersection with two right turn lanes, a road sign, the curve of a shoreline, a buoy. But, it is everything else as well. All the things. My walls at home are lined with books, and the books speak—not just of what is contained in their pages, but of the times I read them, the places I was, the company that surrounded those moments. And there is more, a gesture, my hand on a doorknob, the sudden turn of my head when I look for something, the way my foot falls on a stair. I am out of myself in a flash, or at least out of this time—even though I know that I am inextricably in it—and another older time surges through me. Even when still, this heartbeat explodes into a thousand, a million other heartbeats, and time collapses. And so, beside my own strange face, I also take pleasure in crowds of strange faces, all of whom present unknown avenues, untapped sources of experiences and memories. I know the echoes will come to the strange person I will again be tomorrow.

And so, beside my own strange face, I also take pleasure in crowds of strange faces, all of whom present unknown avenues, untapped sources of experiences and memories. I know the echoes will come to the strange person I will again be tomorrow.

I have a confession. I have a terrible time receiving love. I’m sure that this is true of almost everyone, so, I’m reluctant to make any big claim about it.

I have a confession. I have a terrible time receiving love. I’m sure that this is true of almost everyone, so, I’m reluctant to make any big claim about it.