While I like to write while surrounded by people, once my eyes are on the page, and once my fingers are working, a kind of wall goes up. Writing is solitary. And it is not.

While I like to write while surrounded by people, once my eyes are on the page, and once my fingers are working, a kind of wall goes up. Writing is solitary. And it is not.

The whole point of writing is for there to be a reader.

Every time I write, I am thinking of you. You could be sitting right behind me at this coffee shop in Gainesville, VA. Or at an internet cafe somewhere in Pakistan. You could be someone I have known for years. Or someone who has stumbled into my work on a whim.

When I write, I imagine myself as that “you.” I am the woman writing about transformation in her blog and that man who took a break from writing about horses and Johnny Cash. I am my daughter, who, perhaps, will look back at this years later when she decides she wants to know something more about her father. And I am you, unknown and unknowable, reading this now. And even you, who I have known, once—maybe for a few glorious months—are still unknown.

These days, I wear reading glasses when I write. The glasses give the letters on the screen crisper definition. When I look up though, the world is blurred. I cannot be focused on the there that is twelve feet away from me and the here that is a ranged configuration of black shapes. Letters. I think of all the alphabets and how arbitrary those shapes are—they stand from left to right or right to left. We see a sequence that shapes the way we read and understand the world as much as the simple shapes try to define that word. Why am I watching those random shapes when other human shapes drift in and out of my blurred vision?

Sometimes, I write for me—not to express my thoughts or feelings, but so that sometime later I can become my own reader. I will remember this person who sat in fairly comfortable, if strange, surroundings, among people who spoke my language and people who spoke other unfamiliar languages. I will remember those who sat with me while I wrote or those who slept in rooms nearby. The strange shapes that I decipher will point me to another time, another me. I will treat whatever is contained in these words as properly strange, belonging to someone who is not me, any more than you are not me.

There is a plate at the Freer Gallery in Washington DC. Around the rim are an elongated set of letters in Arabic. Even if you knew what those letters meant, would you know about the person who wrote them before the platter was fired in a hundreds of years old kiln? Or what to make of the carved insignias on a Neolithic disc from China? Sometime, 5000 years from now, will these shapes still make sense? Will they point some future reader back to me? Or to anyone else who writes now?

There is a plate at the Freer Gallery in Washington DC. Around the rim are an elongated set of letters in Arabic. Even if you knew what those letters meant, would you know about the person who wrote them before the platter was fired in a hundreds of years old kiln? Or what to make of the carved insignias on a Neolithic disc from China? Sometime, 5000 years from now, will these shapes still make sense? Will they point some future reader back to me? Or to anyone else who writes now?

I write to be in the moment. I love the process of getting lost in the words, in trying to connect thoughts and feelings to this electronic scrawl. I loved diving back into the world of the djinn day after day and discovering what he—and all the characters in that book—saw and heard and felt. Writing took me out and away from my self, and gave me a place to visit and revisit.

I know all too well that the moment does not last. I write ensconced in both the past and the future. Everything I know—59 years of experience—and everything that will open before me—another 59 years?—balances on the self that writes here. Each time, the words bring me back to the self who wrote that fragment, and I keep returning to that self while I work on a particularly long piece of writing. But that self never remains static—returning requires an effort.

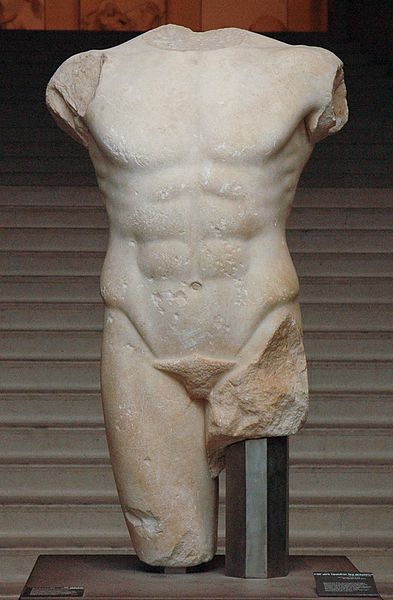

The self that writes is almost more like a mask—something and someone stopped in time. I write in and on that mask, but underneath, on my face, in my hands, and in my heart and mind dreams of change and something I have not imagined continue. Last night I dreamed that I was making dinner—a recipe I did not know with someone I did not know. My mind invents and travels and changes. I long to remove the mask, but I accept the part I play. For now.

There will be another mask, just as there will be another dream, just as today’s experiences will shape me. The mask-maker. The writer. The man. And you, also, always. Perhaps you will find your way to here from wherever you are, and you will find your way back to some unknown place. And write.

And so, I revisit places—the Calders at the National Gallery of Art remind me of the value of clean lines, whimsy, and balance (always balance!). In spite of the heartache, there is beauty—beauty made by hands, not simply discovered in nature. Although that beauty too—the changing fall colors, the scent of the season even as I walk on the National Mall—fills my sails with new wind.

And so, I revisit places—the Calders at the National Gallery of Art remind me of the value of clean lines, whimsy, and balance (always balance!). In spite of the heartache, there is beauty—beauty made by hands, not simply discovered in nature. Although that beauty too—the changing fall colors, the scent of the season even as I walk on the National Mall—fills my sails with new wind.

It seems impossible to me that when I finally see the cathedral at Rouen, I will already know the shadows of the late afternoon sun, and the way the morning light illuminates its porticos. How much of the world do I already know through the eyes of artists—the representations and words of painters and writers?

It seems impossible to me that when I finally see the cathedral at Rouen, I will already know the shadows of the late afternoon sun, and the way the morning light illuminates its porticos. How much of the world do I already know through the eyes of artists—the representations and words of painters and writers? This past fall, I went horse riding for the first time since I rode at a neighbor’s farm when I was 6 or 7. I rode on a horse named “Old General,” a sleepy footed follower of faster horses, but a step up from a rocking chair. Or so I was told. At one point in the ride, our trail guide asked if we wanted to run. It was actually the second time she had asked us; the first time I had gotten my sense of it. The second time, I was ready. Old General and I dashed, finding speed where it had not been before, and we covered the field ahead of my riding companions. Yes, I am competitive. It was one of the best days I had had in a long time.

This past fall, I went horse riding for the first time since I rode at a neighbor’s farm when I was 6 or 7. I rode on a horse named “Old General,” a sleepy footed follower of faster horses, but a step up from a rocking chair. Or so I was told. At one point in the ride, our trail guide asked if we wanted to run. It was actually the second time she had asked us; the first time I had gotten my sense of it. The second time, I was ready. Old General and I dashed, finding speed where it had not been before, and we covered the field ahead of my riding companions. Yes, I am competitive. It was one of the best days I had had in a long time.