When you write every day, images, scenes, bits of dialogue, everything really, come more easily. Writing becomes more like the air one breathes. The random bit of inspiration that seems so important—you sneak off from dinner with a friend to scribble something down in the restroom—becomes less so. Bits and pieces that have purchase assert themselves beyond any given moment.

I often get ideas as I pass from waking to slumber—in liminal moments. Liminal moments are times when one passes from one state to another, when change occurs, is about to occur, or has just occurred. One of the reasons I walk around while I write, and why I spent the summer writing in a school library, is to facilitate those liminal moments—to give myself actual doorways through which I could walk. A small amount of distraction (people walking in and out of the library while I am writing) gives me just enough of a shove from one state of mind to another to open the brighter doors of imagination. I interpret Roethke’s line from “The Waking”—“this shaking keeps me steady”—as a nod toward the role of liminal passages, of actual movement and transition, in the creative process.

Last night as I was drifting off, an idea—the image of a brick (a character perceives people as bricks, and suspects that there might be something entirely un-bricklike contained within those bricks in spite of his perception). I did not write it down, but let it play in my mind as I dropped quickly to sleep. I felt less a need to get up and write the image and bit of internal dialogue, but I repeated it as I dropped off. Later, I dreamed that I wrote it down, and the dream was so deep that I thought I was actually awake when I did it.

In the morning it was gone, until I was on my way to school, looking at the sky, and thinking about sending a text to a friend. I wanted to write something about how the cloud cover looked like batting spilled from inside couch pillows. I thought that it did not look like cotton, but that calling it “polyester batting” would have sour implications. And as I was thinking about that, the brick came back, pleasantly insistent, as did the dream, and the character.

I wondered where I would put this odd reflection. It really isn’t that odd. In the mythology I am using in my book, humans are made from clay, and so a reflection that people seem like bricks is not that unusual for a character to think. Except he is human too, or mostly human, and he wonders why he sees people the way he does, and whether he has become too bricklike. Then he has other thoughts—about fire and the beings made from fire. There is a reason for him to think about this too.

And there was a reason for me to remember, and remember the way I did.

What all this is about is this: inspiration comes, and persists. Go ahead and dash off to the kitchen when company is over, and keep your notebook or writing device of choice handy. However, if you are writing every day—every single day—you may find that you will not feel the same urgency when inspiration comes. It will stick around and wait for the time you assiduously set aside to get to the work. And if it slips away, something else may bring it back as you are in the middle of another thought, looking at the sky while you are driving to work.

It seems impossible to me that when I finally see the cathedral at Rouen, I will already know the shadows of the late afternoon sun, and the way the morning light illuminates its porticos. How much of the world do I already know through the eyes of artists—the representations and words of painters and writers?

It seems impossible to me that when I finally see the cathedral at Rouen, I will already know the shadows of the late afternoon sun, and the way the morning light illuminates its porticos. How much of the world do I already know through the eyes of artists—the representations and words of painters and writers? This past fall, I went horse riding for the first time since I rode at a neighbor’s farm when I was 6 or 7. I rode on a horse named “Old General,” a sleepy footed follower of faster horses, but a step up from a rocking chair. Or so I was told. At one point in the ride, our trail guide asked if we wanted to run. It was actually the second time she had asked us; the first time I had gotten my sense of it. The second time, I was ready. Old General and I dashed, finding speed where it had not been before, and we covered the field ahead of my riding companions. Yes, I am competitive. It was one of the best days I had had in a long time.

This past fall, I went horse riding for the first time since I rode at a neighbor’s farm when I was 6 or 7. I rode on a horse named “Old General,” a sleepy footed follower of faster horses, but a step up from a rocking chair. Or so I was told. At one point in the ride, our trail guide asked if we wanted to run. It was actually the second time she had asked us; the first time I had gotten my sense of it. The second time, I was ready. Old General and I dashed, finding speed where it had not been before, and we covered the field ahead of my riding companions. Yes, I am competitive. It was one of the best days I had had in a long time.

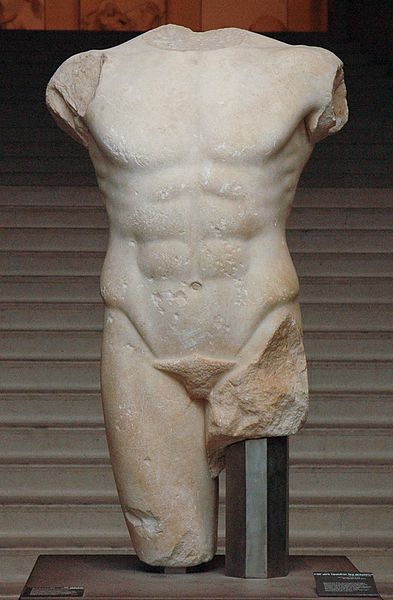

I am looking at a painting made by a French artist of a British building that hangs in an American museum. This seems at once perfectly natural—what else would I be doing? What else would a French artist paint (or an Italian, British, Russian, Afghan, or American)? And where else would a painting be? Of course, this seems only natural because it is what we have become accustomed to, since the time when Ennigaldi-Nanna opened the first museum.

I am looking at a painting made by a French artist of a British building that hangs in an American museum. This seems at once perfectly natural—what else would I be doing? What else would a French artist paint (or an Italian, British, Russian, Afghan, or American)? And where else would a painting be? Of course, this seems only natural because it is what we have become accustomed to, since the time when Ennigaldi-Nanna opened the first museum.