I was asked, “Do you feel old?” It was a question and an accusation.

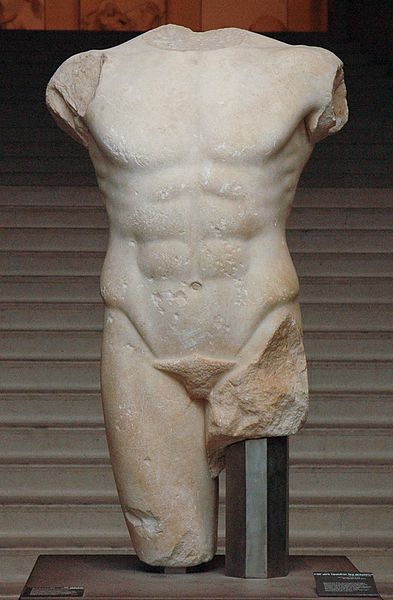

I have reasons to be aware of my age. Over ten years ago, I had knee surgery as a result of years of overuse in swimming. My right shoulder has a tender rotator cuff; like my knees, my shoulder woes began when I was 17 and had a hitch in my freestyle stroke that put stress on the joint. Injuries never exactly go away as I am painfully reminded each time I lift weights with my hands out of a neutral position.

When I trim my beard, the hair falls from the electric razor like snow. The tide of my hairline has ebbed far enough to reveal another furrow on my brow. There are feathery lines that betray my transit. I do not always recognize the face that stares back at me, but I never truly recognized it. I have been surprising myself since before I can remember. Is that me? It is. It still is.

I know more than I did when I was 20, 30, or even 55. The accumulation of knowledge never stops. Each new day brings new articles of knowledge. I learn new ways of seeing the world or thinking about what I do. I gravitate toward books and lessons that show me something I did not know before I began. I am a specialist in my own ignorance. Every few years I feel a desire to overturn my life—uncomfortable in anything that feels like mastery, or rather, what might be mistaken for mastery. Yes, there is a value in going deep into a subject—in tunneling to the heart of a matter. But, to extend the metaphor, does the heart matter if one does not connect it to the bones and nerves and skin? What does the heart matter if it does not move out into the world and connect not just to the other 8 billion human hearts, but to everything living heart, and every other thing that does not have a heart? The more I learn, the more the connections pull at me.

I write—the single consistent strand of the past thirty-five years—because writing is not bound to any single subject. I write about movies, families, love, death, writing, baseball, anatomy, and art. I write about poems I love, and people who anger me to the point of distraction. I write about them to quell the dull ache of calcification and the even duller sense of disappointment with a world that replaces genuine surprise with momentary thrills. I write fiction and poetry to reach into the world and to describe a world that is thrilling—momentarily and for so much longer—but also deeply mysterious.

Writing is a time machine. It returns me to the giddy, carefree, and fearless time of youth. When I was ten, a flood brought the creek water a dozen feet higher than usual. The water rose above the bridge on the road below our house—a house on a hill. I went to the bridge and marveled at the swift brown water that reached the rails that spanned each side of the bridge. I waded into the water and held onto the rails. My feet lifted from the road and trailed behind me as I went hand over hand across the bridge. And once I crossed, I came back the same way.

Later in life, I did similar things, but the feeling then—water rushing past me, my feet straight out behind me, the weight of my body held by my extended arms—only fully returns when I write. And writing lets me shake off the years, not just mine, but all the years. I travel to any time I wish, unstuck from this moment, unlocked from expectation. In The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald writes about romping in the mind of God. Writing is like that. It can be. It must be.

Do I feel old? Positively. I am ancient because my writing carries me to that world—to every world. And I am young, still. Always.

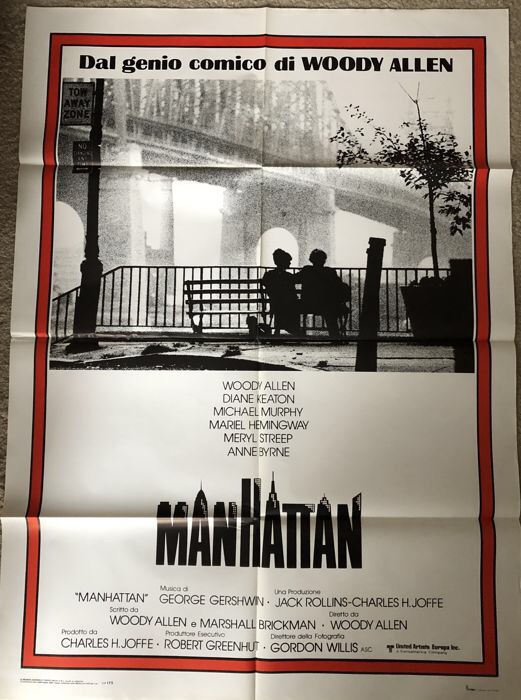

I first saw Manhattan in 1979, when I was 19 and thought myself precocious. I was a sophomore at Swarthmore College, a school full of young people who rebelled in their precociousness. Tracy’s relationship with Isaac simply echoed my sense of myself. Who among my friends would have put a limit on the seventeen-year-old Tracy? We were only steps away from that age; we were not intimidated by 42-year olds. What did we know about power dynamics or anything more than our own blossoming worth in the world? Blossoming? Fuck that—we were valuable and powerful as we were.

I first saw Manhattan in 1979, when I was 19 and thought myself precocious. I was a sophomore at Swarthmore College, a school full of young people who rebelled in their precociousness. Tracy’s relationship with Isaac simply echoed my sense of myself. Who among my friends would have put a limit on the seventeen-year-old Tracy? We were only steps away from that age; we were not intimidated by 42-year olds. What did we know about power dynamics or anything more than our own blossoming worth in the world? Blossoming? Fuck that—we were valuable and powerful as we were.

And so, I revisit places—the Calders at the National Gallery of Art remind me of the value of clean lines, whimsy, and balance (always balance!). In spite of the heartache, there is beauty—beauty made by hands, not simply discovered in nature. Although that beauty too—the changing fall colors, the scent of the season even as I walk on the National Mall—fills my sails with new wind.

And so, I revisit places—the Calders at the National Gallery of Art remind me of the value of clean lines, whimsy, and balance (always balance!). In spite of the heartache, there is beauty—beauty made by hands, not simply discovered in nature. Although that beauty too—the changing fall colors, the scent of the season even as I walk on the National Mall—fills my sails with new wind.

It seems impossible to me that when I finally see the cathedral at Rouen, I will already know the shadows of the late afternoon sun, and the way the morning light illuminates its porticos. How much of the world do I already know through the eyes of artists—the representations and words of painters and writers?

It seems impossible to me that when I finally see the cathedral at Rouen, I will already know the shadows of the late afternoon sun, and the way the morning light illuminates its porticos. How much of the world do I already know through the eyes of artists—the representations and words of painters and writers?