Some of my students are aghast at the idea of reading a book a second time, let alone a third or forth, or fifteenth time. The life of a teacher means revisiting books again and again. They become habits. The past dozen years brought steady stops in S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders and Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, Homer’s Odyssey, and maybe Shakespeare’s Macbeth. All became exceedingly familiar territory—terra too cognito—and I welcomed the changes that a change of job and change of curriculum brought this year. I taught half a dozen book I had not read in years. The freshness helped revive my vision.

Of course, repetition is the backbone of study. There isn’t a piece, whether film, book, or painting, that I have not poured over. And over. Some works hold up to repeated visits—this is especially of true of paintings and sculptures. I have sat in front of some paintings for hours, and then gone back a year later to do more. The ability to give concentrated attention to something is a rare quality. And yet, I find myself loosing the fire for return visits and viewings, even for old favorites. How many times can I return to Hamlet, or It’s a Wonderful Life, or Wings of Desire? I know there are things I have not seen, and they call to me.

With spring, my attention is pulled back to baseball, and a group of friends with whom I have played rotisserie baseball for nearly thirty years. I have risen at odd hours when the season began in Japan, as it did again this season. I did not wake to watch early in the morning, but acknowledged the game at arm’s length. I almost did not play our little game this season, almost tired of keeping track of scores and statistics. 162 games and fifteen teams works out to nearly 2500 events to be aware of in some nagging fashion. Enough already.

How much has repetition and routine play a part in life? Too much. At times it seemed that I flew on autopilot, barely aware of the ground beneath me or the time that slipped past, never to return. Sometimes the routine is good—I don’t give more than passing thought to breakfast and lunch when I am busy. I eat the same thing, more or less, day after day. Perhaps my life would be better if I added variations here, but I have had other pressing concerns, like a Stephen Greenblatt essay about Hamlet. There are ways to keep the standards fresh. Still, there must be more.

I changed large parts of my life this past year—there were many reasons, but one was to interrupt the flow that had become too familiar, too easy. I wanted to drive up to a different door—my door. It did not have to be more beautiful—and it wasn’t—it just had to be different. My work as a teacher, although familiar enough, had to take me to different books an different students. And I needed to extricate myself from a years long creative drought. I needed to write to be alive.

This past December, I traveled to a new place, London, to which I had meant to travel almost thirty years ago. I traveled after I did a series of new things, each one satisfying, but each fueling a desire for more. Almost everything that has been part of the solid ritual of my daily routine tastes bland. I don’t hanker for extremes—a solo sailing venture around the world, or an ascent up some foreboding mountain, or a year in a seraglio—I yearn to encounter something as if for the first time. I wish to be a beginner again, with a clean slate ahead of me.

This past December, I traveled to a new place, London, to which I had meant to travel almost thirty years ago. I traveled after I did a series of new things, each one satisfying, but each fueling a desire for more. Almost everything that has been part of the solid ritual of my daily routine tastes bland. I don’t hanker for extremes—a solo sailing venture around the world, or an ascent up some foreboding mountain, or a year in a seraglio—I yearn to encounter something as if for the first time. I wish to be a beginner again, with a clean slate ahead of me.

It will not be. There is much that I cannot jettison (Overboard! Overboard!), and some of which has been central to my life. But to bring my daughter along for the ride. To carry my brave and loving heart into boundless possibility. To write without care for sharp tongued critique. To go, and keep going.

I recognize that when I felt at my best, I was a student, learning, reading, discovering with a vigor that few matched. Right now my writing carries me vigorously to some new place—an undiscovered country that is beyond death—the little death of stagnation and routine, the larger death of a withered soul. I need to find a way to return this more adventurous, more daring, more profound sense of discovery to the rest of my life, to every aspect of my life. To become a masterful student again. Even while I wear the mantle of expert, I am an expert explorer. It is time to honor that. And go.

Perhaps my writing will be enough to answer that call during the long school year. My work feels, for the first time in longer than I care to admit, durable and ecstatic. However, I cannot let anything—or anyone, even myself—keep me from discovery. There must be time for new thoughts, new places, and a new world that will animate my work and revive my old heart. Here—there, and everywhere—I go.

I have been struggling with masculinity as of late. Which is to say, struggling with ambition. Or struggling with my career choices. Or struggling with relationship choices. Or, simply struggling. Because I am a man, I am struggling on the somewhat closed field of masculinity. I haven’t always thought of it that way, and yet, there it is. I have avoided masculinity for dozens of reasons.

I have been struggling with masculinity as of late. Which is to say, struggling with ambition. Or struggling with my career choices. Or struggling with relationship choices. Or, simply struggling. Because I am a man, I am struggling on the somewhat closed field of masculinity. I haven’t always thought of it that way, and yet, there it is. I have avoided masculinity for dozens of reasons.

The charm of London is found in its strange alleyways, endlessly curled streets, and tucked away history. If there is a grid, and in some way, there is, it is bent around the past and the ox bow turns of the Thames, and everything attached to it has been attached in a haphazard fashion. For instance, the coagulation of insurance buildings in central London: the gherkin, the cheese-grater, the scalpel, and the inside-out building; defy any sense of a rational aesthetic plan. Or the juxtaposition of the Tower on one side of the Thames and the glass pineapple of the City Hall just across the river.

The charm of London is found in its strange alleyways, endlessly curled streets, and tucked away history. If there is a grid, and in some way, there is, it is bent around the past and the ox bow turns of the Thames, and everything attached to it has been attached in a haphazard fashion. For instance, the coagulation of insurance buildings in central London: the gherkin, the cheese-grater, the scalpel, and the inside-out building; defy any sense of a rational aesthetic plan. Or the juxtaposition of the Tower on one side of the Thames and the glass pineapple of the City Hall just across the river. And so London’s history is oddly folded into the cityscape as well. A tour through the city—you cannot tour the whole city, or tour it on a bus; you must walk it—folds two thousand years of history, creased around a Roman occupation, a French conquest in 1066, and a fire that destroyed 80% of the city in 1666. And the city is just the square mile that had been walled and gated, but is now open and underlaced with a rail system that carries you quickly to nearly every point beyond the old wall.

And so London’s history is oddly folded into the cityscape as well. A tour through the city—you cannot tour the whole city, or tour it on a bus; you must walk it—folds two thousand years of history, creased around a Roman occupation, a French conquest in 1066, and a fire that destroyed 80% of the city in 1666. And the city is just the square mile that had been walled and gated, but is now open and underlaced with a rail system that carries you quickly to nearly every point beyond the old wall. There is an orderliness to the whole affair. Announcements in the Underground direct people where to walk down hallways and on escalators. Advertisements along the walls of the stations counsel caution with wallets and and advise care with alcohol. “Mind the Gap” is stenciled on the ground where the trains stop, and cheeky announcers corral riders whose fancy Italian made shoes have strayed over the yellow safety line. Cross walks show a green walker when it’s time to cross—around Trafalgar Square the walkers take on a variety of LGBT friendly forms: couples and symbols. Just remember to cross when the green light comes!

There is an orderliness to the whole affair. Announcements in the Underground direct people where to walk down hallways and on escalators. Advertisements along the walls of the stations counsel caution with wallets and and advise care with alcohol. “Mind the Gap” is stenciled on the ground where the trains stop, and cheeky announcers corral riders whose fancy Italian made shoes have strayed over the yellow safety line. Cross walks show a green walker when it’s time to cross—around Trafalgar Square the walkers take on a variety of LGBT friendly forms: couples and symbols. Just remember to cross when the green light comes! I had always shrugged off the idea of traveling to the Grand Canyon. I was one of those, “what’s the big deal about a big hole in the ground” skeptics. I was wrong. Of course I was wrong. The Grand Canyon is an amazement—and of course, I was properly amazed when I saw it—looking into two billion years of rock will do that, should do that. I realized that what I had held aside was not the geology or the landscape, but the travel. Why had I discounted my ability to be amazed by travel? I had done it all my life. Going, all kinds of going, even if so much of it has been more local—on this continent, in this country—has been part of me all my life.

I had always shrugged off the idea of traveling to the Grand Canyon. I was one of those, “what’s the big deal about a big hole in the ground” skeptics. I was wrong. Of course I was wrong. The Grand Canyon is an amazement—and of course, I was properly amazed when I saw it—looking into two billion years of rock will do that, should do that. I realized that what I had held aside was not the geology or the landscape, but the travel. Why had I discounted my ability to be amazed by travel? I had done it all my life. Going, all kinds of going, even if so much of it has been more local—on this continent, in this country—has been part of me all my life. I loved airplanes and airports. Departures were invitations to new adventures. When I traveled with my family, I usually sat alone—the hazard or benefit of being an odd numbered group. I took my first plane flight alone when I went to Iowa to swim; I was 15. I traveled by train and bus alone all through my early adult life. I usually traveled to visit friends. However, I also went to cities to simply see them, to look at buildings, and camp in museums—visiting and revisiting works of art that held sway over my imagination.

I loved airplanes and airports. Departures were invitations to new adventures. When I traveled with my family, I usually sat alone—the hazard or benefit of being an odd numbered group. I took my first plane flight alone when I went to Iowa to swim; I was 15. I traveled by train and bus alone all through my early adult life. I usually traveled to visit friends. However, I also went to cities to simply see them, to look at buildings, and camp in museums—visiting and revisiting works of art that held sway over my imagination. There were trips under sail with my father and brothers. These were tests as well as trips. The ocean makes us foreign to ourselves, our bodies not made to be perpetually wet, and perpetually in motion—shaken and stirred. I have never been anywhere larger than surrounded by sky and ocean, never felt as alive, nor as alone.

There were trips under sail with my father and brothers. These were tests as well as trips. The ocean makes us foreign to ourselves, our bodies not made to be perpetually wet, and perpetually in motion—shaken and stirred. I have never been anywhere larger than surrounded by sky and ocean, never felt as alive, nor as alone. In many ways, I take solace in being surrounded by memories, and there are some that I purposefully mine. The routine of the same lunch—on most days—reminds me of years of similar lunches from the time I was five—earlier—until just last week—and all the lunches in between. I feel comforted by the way those memories permeate my present so easily.

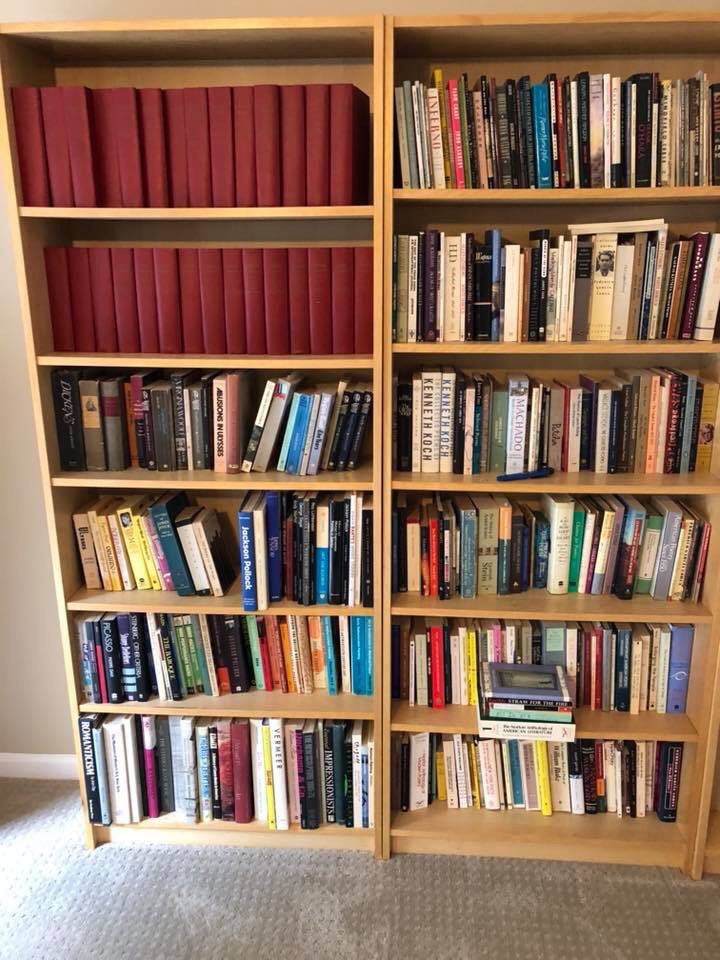

In many ways, I take solace in being surrounded by memories, and there are some that I purposefully mine. The routine of the same lunch—on most days—reminds me of years of similar lunches from the time I was five—earlier—until just last week—and all the lunches in between. I feel comforted by the way those memories permeate my present so easily. I have written about the powerful memories associated with places—a rolling set of hills on a road headed north, an intersection with two right turn lanes, a road sign, the curve of a shoreline, a buoy. But, it is everything else as well. All the things. My walls at home are lined with books, and the books speak—not just of what is contained in their pages, but of the times I read them, the places I was, the company that surrounded those moments. And there is more, a gesture, my hand on a doorknob, the sudden turn of my head when I look for something, the way my foot falls on a stair. I am out of myself in a flash, or at least out of this time—even though I know that I am inextricably in it—and another older time surges through me. Even when still, this heartbeat explodes into a thousand, a million other heartbeats, and time collapses.

I have written about the powerful memories associated with places—a rolling set of hills on a road headed north, an intersection with two right turn lanes, a road sign, the curve of a shoreline, a buoy. But, it is everything else as well. All the things. My walls at home are lined with books, and the books speak—not just of what is contained in their pages, but of the times I read them, the places I was, the company that surrounded those moments. And there is more, a gesture, my hand on a doorknob, the sudden turn of my head when I look for something, the way my foot falls on a stair. I am out of myself in a flash, or at least out of this time—even though I know that I am inextricably in it—and another older time surges through me. Even when still, this heartbeat explodes into a thousand, a million other heartbeats, and time collapses. And so, beside my own strange face, I also take pleasure in crowds of strange faces, all of whom present unknown avenues, untapped sources of experiences and memories. I know the echoes will come to the strange person I will again be tomorrow.

And so, beside my own strange face, I also take pleasure in crowds of strange faces, all of whom present unknown avenues, untapped sources of experiences and memories. I know the echoes will come to the strange person I will again be tomorrow. “What do I have to say?”

“What do I have to say?”

I don’t believe in fate—providence, if you will. If there is a plan, it does not proscribe outcomes. Rather we wander in and out of circumstances bumping into two sets of patterns—those we make out of our lives, and those that are beyond our immediate control. Life goes out of balance when we cannot get the two patterns to jibe—when we cannot reconcile ourselves to the patterns that exist. Out of balance we can neither accept what has happened in our lives or we cannot break those patterns and create new ones that are made from familiar pieces but reflect possibilities that we had not imagined. Out of balance we fight against the patterns that life provides, missing obvious signs (rising temperatures, repeated cruelties, even the tender messages of love) and careening against the walls of a maze that we cannot perceive and causing damage to ourselves and those around us.

I don’t believe in fate—providence, if you will. If there is a plan, it does not proscribe outcomes. Rather we wander in and out of circumstances bumping into two sets of patterns—those we make out of our lives, and those that are beyond our immediate control. Life goes out of balance when we cannot get the two patterns to jibe—when we cannot reconcile ourselves to the patterns that exist. Out of balance we can neither accept what has happened in our lives or we cannot break those patterns and create new ones that are made from familiar pieces but reflect possibilities that we had not imagined. Out of balance we fight against the patterns that life provides, missing obvious signs (rising temperatures, repeated cruelties, even the tender messages of love) and careening against the walls of a maze that we cannot perceive and causing damage to ourselves and those around us.