I graduated from SUNY-Binghamton with a Ph.D. in English Literature/Creative Writing in 1994. Before I went to graduate school, I did not know what I wanted to be. I had written a little earlier in life, and had taken a fiction workshop while I was an undergraduate, but my sense of myself as a writer was hazy at best. Still, I had done some work and I applied to writing programs in the spring of 1988. I was accepted at Binghamton.

While I was in graduate school, I wrote stories, a novel that I shelved, some poetry, and essays. I also wrote a slew of academic papers. Mostly, I read furiously and widely, delving into a world of literature and philosophy that had not existed for me before I began this turn in my life. I still have many of the books that I read in those six years and they are either a bulwark or an anchor. Now, they seem more like part of a wall that divided my life into the time when I did not write, the time I discovered writing, and the time I stopped writing.

That time ended in 2018 when I considered moving away from family and the jobs I held in Norfolk. I had been separated and divorced for four years. Calamity at one of my jobs resonated in my life. I was at sea. I needed to find a ground that was not defined by the needs and desires of other people. I needed, frankly, to be selfish and directed. I do not believe that it is a surprise (to me at least) that my colleagues sent me packing with the book, The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fuck when I left in August of 2018. Message received.

Because I did give a fuck — too many fucks — not just in my professional work and personal life, but in my writing. Unlike some of my one time classmates, I felt called to writing not so much because I had a need to express myself, but almost in spite of any need to exclaim, “Here I am!” I was obsessed with getting at some ineffable and intractable truth that existed outside my narrow sense of self. I wrote with an evangelical zeal. Can I say that art motivated by such a keening has little easy air to breathe? It does not. My stories, even when they were fantastic, needed to tread more often on the ground.

When I started writing this blog in 2014, I was in China to adopt my daughter. I started to write about simple human truths that were grounded in my simple human experiences. I hoped that my observations would have some resonance with others, but I wrote without too much of a concern for an audience. The work proceeded in fits and starts after that initial push. And then it flared into this—a daily practice of reflection and direction. That fire lit the flame of the novel I finished in August and has carried me into a second.

My writing projects since May of 2018 have produced over 500 pages of words. Some are good. Some are better. My nonfiction has been largely about my writing and writing in general. My fiction has just been a story about a Djinn, almost a retelling of an older—much older—story, with some of my preoccupations thrown in for good measure.

Writing (fiction and nonfiction) has felt revivifying. I have enjoyed the deeper reflection and playful invention. The writing has come more easily and far more consistently than anything else and at any time I have ever written. Ever. I have looked forward to the task and have left it—whether I write for an hour or the better part of a day—feeling replenished. More will—and does—come.

When I shared this insight—500 pages! More is coming!—with a friend, I did so with the proviso: “in spite of the past year.” She corrected me: “Because of it.” Perhaps so. Perhaps I spent the past year and a half knocking myself off my moorings just so that I could get this work done, just so that I could reclaim all that I had feared was lost.

I told another friend that I felt a kind of urgency to write. She worried that I was ill or distressed. Yes, I have been distressed. Old wounds have haunted me and focused my attention. I have allowed them the space to heal. And have used the writing to help me heal.

While the writing has helped me gird myself against that distress, it has also allowed me to wrap myself in joy. I feel that joy more profoundly now than when I was starting out some thirty years ago. The old uncertainties have fallen away. I do not ask, “Is it good enough? Will there be another? Do I have the right?” Instead, I take solace in a more durable method that suits my heart and mind. I go this way.

It seems impossible to me that when I finally see the cathedral at Rouen, I will already know the shadows of the late afternoon sun, and the way the morning light illuminates its porticos. How much of the world do I already know through the eyes of artists—the representations and words of painters and writers?

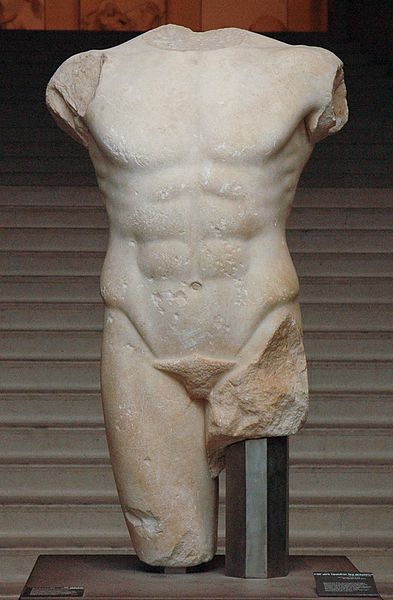

It seems impossible to me that when I finally see the cathedral at Rouen, I will already know the shadows of the late afternoon sun, and the way the morning light illuminates its porticos. How much of the world do I already know through the eyes of artists—the representations and words of painters and writers? I am looking at a painting made by a French artist of a British building that hangs in an American museum. This seems at once perfectly natural—what else would I be doing? What else would a French artist paint (or an Italian, British, Russian, Afghan, or American)? And where else would a painting be? Of course, this seems only natural because it is what we have become accustomed to, since the time when Ennigaldi-Nanna opened the first museum.

I am looking at a painting made by a French artist of a British building that hangs in an American museum. This seems at once perfectly natural—what else would I be doing? What else would a French artist paint (or an Italian, British, Russian, Afghan, or American)? And where else would a painting be? Of course, this seems only natural because it is what we have become accustomed to, since the time when Ennigaldi-Nanna opened the first museum.