There are imaginary places that call to us. Illyria. Macondo–though be careful of that one, friend. The Invisible Cities that Polo reports on to the Khan. And Cocaigne.

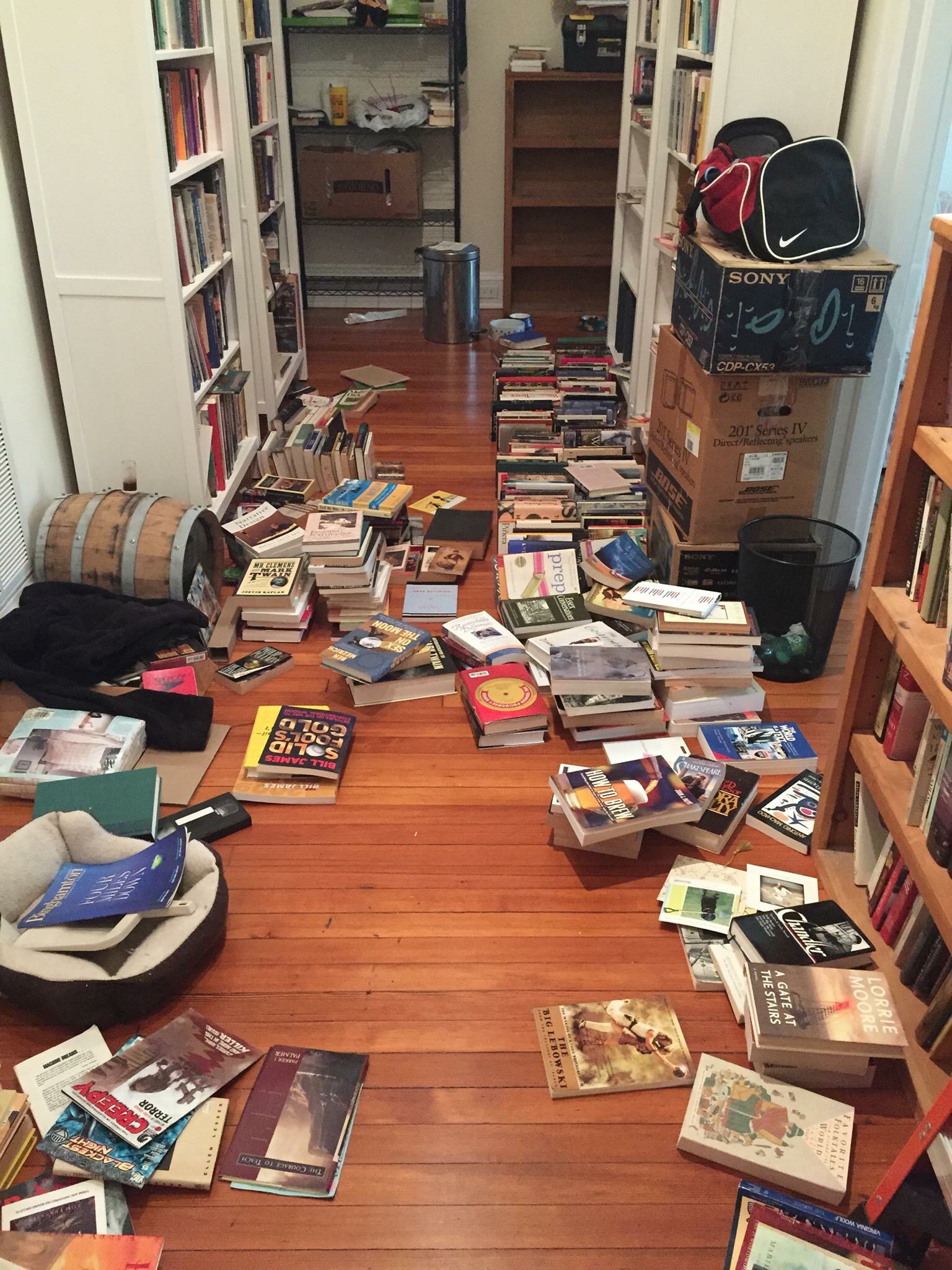

And so, at the end of the day, when I have spent the precious fortune of my wit and energy, spent it for what? Money? Success? Some recognizable residue that others may tout as virtue? I return to the nearest country I can find–the one adrift in the books on my shelves, or the sea of my imagination. Return traveler, with ships once more laden with waking dreams.

Until such time as I may board a ship, an airplane, or some contrivance to carry me into strange and wonderful streets, I have this. Baudelaire…

L’Invitation Au Voyage

There is a wonderful country, a country of Cocaigne, they say, that I dream of visiting with an old love. A strange country lost in the mists of the North and that might be called the East of the West, the China of Europe, so freely has a warm and capricious fancy been allowed to run riot there, illustrating it patiently and persistently with an artful and delicate vegetation.

A real country of Cocaigne where everything is beautiful, rich, honest and calm; where order is luxury’s mirror; where life is unctuous and sweet to breathe; where disorder, tumult, and the unexpected are shut out; where happiness is wedded to silence; where cooking is poetic, rich, and yet stimulating as well; where everything, dear love, resembles you.

You know that feverish sickness which comes over us in our cold despairs, that nostalgia for countries we have never known, that anguish of curiosity? There is a country that resembles you, where everything is beautiful, rich, honest and calm, where fancy has built an decorated an Occidental China, where life is sweet to breathe, where happiness is wedded to silence. It is there we must live, it is there we must die.

Yes, it is there we must go to breathe, to dream, and to prolong the hours in an infinity of sensations. A musician has written l’Invitation a la valse; who will write l’Invitation au voyage that may be offered to the beloved, to the chosen sister?

Yes, in such an atmosphere it would be good to live—where there are more thoughts in slower hours, where clocks strike happiness with a deeper, a more significant solemnity.

On shining panels or on a dark rich and gilded leathers, discreet paintings repose, as deep, calm and devout as the souls of the painters who depicted them. Sunsets throw their glowing colors on the walls of the dining-room and drawing-room, sifting softly through lovely hangings or intricate high windows with mullioned panes. All the furniture is immense, fantastic, strange, armed with locks and secrets like all civilized souls. Mirrors, metals, fabrics, pottery, and works of the goldsmith’s art play a mute mysterious symphony for the eye, and every corner, every crack, every drawer and curtain’s fold breathes forth a curious perfume, a perfume of Sumatra whispering come back, which is the soul of the abode.

A true country of Cocaigne, I assure you, where everything is rich, shining and clean like a good conscience or well-scoured kitchen pots, like chiseled gold or variegated gems! All the treasures of the world abound there, as in the house of a laborious man who has put the whole world in his debt. A singular country and superior to all others, as art is superior to Nature who is transformed by dream corrected, remodeled and adorned.

Let them seek and seek again, let them endlessly push back the limits of happiness, those horticultural Alchemists! Let them offer prizes of sixty, a hundred florins for the solution of their ambitious problems! As for me, I found found my black tulip, I have found my blue dahlia!

Incomparable flower, rediscovered tulip, allegorical dahlia, it is there, is it not, in that beautiful country, so calm, so full of dream, that you must live, that you must bloom? Would you not be framed within your own analogy, would you see yourself reflected in your own correspondence, as the mystics say?

Dreams! Always dreams! And the more ambitious and delicate the soul, all the more impossible the dreams. Every man possesses his own dose of natural opium, ceaselessly secreted and renewed, and from birth to death how many hours can we reckon of positive pleasure, of successful and decided action? Shall we ever live in, be a part of, that picture my imagination has painted, and that resembles you?

These treasures, these furnishings, this luxury, this order, these perfumes, and these miraculous flowers, they are you! And you are the great rivers too, and the calm canals. And those great ships that they bear along laden with riches and from which rise the sailors’ rhythmic chants, they are my thoughts that sleep or that rise with the swell of your breast. You lead them gently toward the sea which is the Infinite, as you mirror the sky’s depth in the crystalline purity of your soul;—and when, weary with the rolling waters and surfeited with the spoils of the Orient, they return to their port of call, still they are my thoughts coming back, enriched from the Infinite to you.

The impulse is to judge, and then to correct. Don’t do that, do this. Or at the very least, Don’t do that.

The impulse is to judge, and then to correct. Don’t do that, do this. Or at the very least, Don’t do that.

Almost thirty years ago, I was eating dinner at a little restaurant on the edges of Johnson City and Binghamton, New York. My mentor and her husband had invited me along. These were heady occasions, full of discussions about writing and literature, and the program in which we all worked. I was a student, but, still, I worked. On this particular occasion, they started talking about writers manqué—although I heard it as writer manqués. It was a new word for me. Manqué: having failed to become what one might have become; unfulfilled. They started listing writers who had been in the program, writers who had published and stopped, and writers who were currently in the program. It was sharp and cruel, and the sobriquet stood out as one to be avoided at all costs. These may not have been eternal footmen, but there was snickering enough to go around.

Almost thirty years ago, I was eating dinner at a little restaurant on the edges of Johnson City and Binghamton, New York. My mentor and her husband had invited me along. These were heady occasions, full of discussions about writing and literature, and the program in which we all worked. I was a student, but, still, I worked. On this particular occasion, they started talking about writers manqué—although I heard it as writer manqués. It was a new word for me. Manqué: having failed to become what one might have become; unfulfilled. They started listing writers who had been in the program, writers who had published and stopped, and writers who were currently in the program. It was sharp and cruel, and the sobriquet stood out as one to be avoided at all costs. These may not have been eternal footmen, but there was snickering enough to go around. Nonetheless, the fear of being unfulfilled lurks. In a

Nonetheless, the fear of being unfulfilled lurks. In a  Is it any surprise that repetition plays a significant role in my life? I came of age as an athlete knocking out sets of 30 200 yard freestyle swims. They were yardage eaters—a quick and dirty way to lay in 6000 yards of workout and buy time for rest of the yards that the coach had in mind. We finished them at intervals of 2:30, 2:20, and 2:10, which left 50 minutes for the rest of the practice—an easy pace for the two to four thousand yards to come. Pushing off the wall every two minutes and thirty seconds, there was time for conversation between swims. Leaving at every two minutes and ten seconds put a crimp on anything other than brief exchanges: “This sucks,” “Stop hitting my feet,” “I’m hungry.”

Is it any surprise that repetition plays a significant role in my life? I came of age as an athlete knocking out sets of 30 200 yard freestyle swims. They were yardage eaters—a quick and dirty way to lay in 6000 yards of workout and buy time for rest of the yards that the coach had in mind. We finished them at intervals of 2:30, 2:20, and 2:10, which left 50 minutes for the rest of the practice—an easy pace for the two to four thousand yards to come. Pushing off the wall every two minutes and thirty seconds, there was time for conversation between swims. Leaving at every two minutes and ten seconds put a crimp on anything other than brief exchanges: “This sucks,” “Stop hitting my feet,” “I’m hungry.” The thing about writing that some people will never understand is that for the writer, it is not cerebral. Writing is physical. I feel exhausted, physically spent, after writing. Not exactly the same as after a work out, or after a night of intimacy, but I will push myself until my body shakes. I stop when I am done, when I have hit a physical limit. I do not believe that people who do not write, seriously write, understand this.

The thing about writing that some people will never understand is that for the writer, it is not cerebral. Writing is physical. I feel exhausted, physically spent, after writing. Not exactly the same as after a work out, or after a night of intimacy, but I will push myself until my body shakes. I stop when I am done, when I have hit a physical limit. I do not believe that people who do not write, seriously write, understand this.

History is a story of discontinuous events—events that collide like weather systems or galaxies, having barely understood origins, and even less decipherable records. All the witnesses were destroyed in the collision. What they saw, what they thought, and what they felt—even if they recorded their observations on stone, paper, steel, or silicone, have been destroyed along with them. We are living in the age of delusion, in which we believe in the sanctity of our recorded history—either self-scribbled or captured by another.

History is a story of discontinuous events—events that collide like weather systems or galaxies, having barely understood origins, and even less decipherable records. All the witnesses were destroyed in the collision. What they saw, what they thought, and what they felt—even if they recorded their observations on stone, paper, steel, or silicone, have been destroyed along with them. We are living in the age of delusion, in which we believe in the sanctity of our recorded history—either self-scribbled or captured by another. Second, in the musical Hamilton (which was also part of this trip to London), the character of George Washington warns Hamilton that we do not control who writes our stories. He’s telling this to a man who believes in his power to literally write his own story—and to use his words to cement his reality. He can’t—and doesn’t. His wife, Eliza, sends his legacy forward—and Lin Manuel Miranda brings us her legacy. But, as Miranda admits in interviews, even this moment for Hamilton—and therefore, for him as well—is provisional and subject to changing tastes and critical opinion.

Second, in the musical Hamilton (which was also part of this trip to London), the character of George Washington warns Hamilton that we do not control who writes our stories. He’s telling this to a man who believes in his power to literally write his own story—and to use his words to cement his reality. He can’t—and doesn’t. His wife, Eliza, sends his legacy forward—and Lin Manuel Miranda brings us her legacy. But, as Miranda admits in interviews, even this moment for Hamilton—and therefore, for him as well—is provisional and subject to changing tastes and critical opinion.