Sing in me muse, and through me tell the story…

Sing in me muse, and through me tell the story…

So began the first translation, by Robert Fitzgerald, of The Odyssey that I read. Later, I taught another translation, by Robert Fagles, that began:

Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns…

More recently, Emily Wilson offered this:

Tell me about a complicated man,/ Muse…

No matter the translation or framing of the tale and Odysseus, the poet turns to the muse to provide the story and the song. It seems like a quaint notion. These days we mine our lives for the sources of stories.

Even Gabriel Garcia Marquez, perhaps somewhat disingenuously, claimed that all the impossible elements of One Hundred Years of Solitude were true. His memoir, Living to Tell the Tale, reads like a revelation, and it makes all that seemed strange in his novel strangely normal—at least for that time and place. Of course, Marquez famously recounts the genesis of that novel—he was headed away on vacation with his family when he realized that the voice of the book was the voice of his grandmother telling incredible stories in the most matter-of-fact voice. He turned the car around and started the work that would define him as a writer. His grandmother was, in a way, his muse.

Even Gabriel Garcia Marquez, perhaps somewhat disingenuously, claimed that all the impossible elements of One Hundred Years of Solitude were true. His memoir, Living to Tell the Tale, reads like a revelation, and it makes all that seemed strange in his novel strangely normal—at least for that time and place. Of course, Marquez famously recounts the genesis of that novel—he was headed away on vacation with his family when he realized that the voice of the book was the voice of his grandmother telling incredible stories in the most matter-of-fact voice. He turned the car around and started the work that would define him as a writer. His grandmother was, in a way, his muse.

Why do writers have muses—things, people, animals—outside of themselves to give their work a nearly mystical, almost divine impetus? The writer faces inward and outward tidal forces. A writer works the tension between the inner voice—the thing that writes—and the outer world—what she or he writes about. Writers attempt to portray the outer world, even if it is a fantastic and impossible world, truthfully, crafting a vivid continuous dream in words, crafting it with the inner voice.

Of course, what a writer makes is not the world: it is an approximation, a copy, a simulacrum, an aspiring reality that with a combination of skill and luck convinces the reader. Or hoodwinks. I can never tell. Perhaps enchants. The writer makes a world, or something like a world, and populates it with minds and bodies, cities and mountains, oceans and sea monsters. Even if all these elements resemble something found in the real world—the world of the reader—each part comes from within the writer.

This act of creation is nearly divine. The writer is the maker of worlds. Even when Dickens charts London’s streets—we can locate Scrooge’s counting house and guess, fairly accurately, where his lonely lodgings were—they are shoved two inches to the left of the world we know. This London is not London. By creating a new world, the writer seeks to emulate the world that is, but also to replace it. For the time the reader enters the dream, it is a world that could be, not a world that is, and the dream reveals something particular, something full of twists and turns and complications.

While the writer uncovers the words that capture this world, she or he enters the world, and if the writer believes the words—and she must! he must!—then the inner world threatens to obliterate the outer one. After all, there is something about that outer world that the writer seeks to correct. The ghosts visit and Scrooge reforms—is literally made into someone new. This is the world that should be—where a miserly and selfish investor can become “as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world.”

While the writer uncovers the words that capture this world, she or he enters the world, and if the writer believes the words—and she must! he must!—then the inner world threatens to obliterate the outer one. After all, there is something about that outer world that the writer seeks to correct. The ghosts visit and Scrooge reforms—is literally made into someone new. This is the world that should be—where a miserly and selfish investor can become “as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world.”

The writer sees what could be, like Cassandra, the unheeded prophet of myth. Some writers simply disgorge the terrible truth of what is, like an oracle who disdains both irony and hope. There is no redemption, just inexorable weight—think of the novels of Stephen Crane, or Gustave Flaubert. Their worlds may be imagined, but the imagined reality is cautionary: there is no escaping this gravity. Let me pause to say that dystopian fiction while cautionary, by making the possible reality so obviously awful, opens a kind of door to redemption: all this could be avoided. The realist, on the other hand, sees no way around the unbearable truth.

Either writer—redemptive or admonishing—seeks some anchor outside the work. By locating the inner voice in some external force, a muse, whether divine or closer at hand, the writer can dissociate from that other world. It isn’t in me! It comes from Erato, or my lover, or my cat, or the messages on the television. The muse is a hedge against being swallowed by that inner world. Madness is a double edged sword, and there is divine madness in writing. “Much madness is divinest Sense,” Emily Dickinson begins her poem. The muse keeps the madness at a distance.

I am not suggesting that writers are mad—that trope has little interest or value to me. Writers bear the weight of vision, and seek ways to allay that weight. Some retreat from the world—the noisiness of life interrupts the vision that animates their existence. Some bound into the world—seeking febrile connections to the world, and allowing all those connections to illuminate their visions. Some stop writing, and I believe that even then they suffer. I know so. Vision is persistent and obstinate.

Sing, sing, or tell. We seek a trick, a magic act, inspiration to crack through the hard shell, and once again, create and fly. A muse, or otherwise, a simple spell of words to open the way.

Country Living posted a

Country Living posted a

The charm of London is found in its strange alleyways, endlessly curled streets, and tucked away history. If there is a grid, and in some way, there is, it is bent around the past and the ox bow turns of the Thames, and everything attached to it has been attached in a haphazard fashion. For instance, the coagulation of insurance buildings in central London: the gherkin, the cheese-grater, the scalpel, and the inside-out building; defy any sense of a rational aesthetic plan. Or the juxtaposition of the Tower on one side of the Thames and the glass pineapple of the City Hall just across the river.

The charm of London is found in its strange alleyways, endlessly curled streets, and tucked away history. If there is a grid, and in some way, there is, it is bent around the past and the ox bow turns of the Thames, and everything attached to it has been attached in a haphazard fashion. For instance, the coagulation of insurance buildings in central London: the gherkin, the cheese-grater, the scalpel, and the inside-out building; defy any sense of a rational aesthetic plan. Or the juxtaposition of the Tower on one side of the Thames and the glass pineapple of the City Hall just across the river. And so London’s history is oddly folded into the cityscape as well. A tour through the city—you cannot tour the whole city, or tour it on a bus; you must walk it—folds two thousand years of history, creased around a Roman occupation, a French conquest in 1066, and a fire that destroyed 80% of the city in 1666. And the city is just the square mile that had been walled and gated, but is now open and underlaced with a rail system that carries you quickly to nearly every point beyond the old wall.

And so London’s history is oddly folded into the cityscape as well. A tour through the city—you cannot tour the whole city, or tour it on a bus; you must walk it—folds two thousand years of history, creased around a Roman occupation, a French conquest in 1066, and a fire that destroyed 80% of the city in 1666. And the city is just the square mile that had been walled and gated, but is now open and underlaced with a rail system that carries you quickly to nearly every point beyond the old wall. There is an orderliness to the whole affair. Announcements in the Underground direct people where to walk down hallways and on escalators. Advertisements along the walls of the stations counsel caution with wallets and and advise care with alcohol. “Mind the Gap” is stenciled on the ground where the trains stop, and cheeky announcers corral riders whose fancy Italian made shoes have strayed over the yellow safety line. Cross walks show a green walker when it’s time to cross—around Trafalgar Square the walkers take on a variety of LGBT friendly forms: couples and symbols. Just remember to cross when the green light comes!

There is an orderliness to the whole affair. Announcements in the Underground direct people where to walk down hallways and on escalators. Advertisements along the walls of the stations counsel caution with wallets and and advise care with alcohol. “Mind the Gap” is stenciled on the ground where the trains stop, and cheeky announcers corral riders whose fancy Italian made shoes have strayed over the yellow safety line. Cross walks show a green walker when it’s time to cross—around Trafalgar Square the walkers take on a variety of LGBT friendly forms: couples and symbols. Just remember to cross when the green light comes! History is a story of discontinuous events—events that collide like weather systems or galaxies, having barely understood origins, and even less decipherable records. All the witnesses were destroyed in the collision. What they saw, what they thought, and what they felt—even if they recorded their observations on stone, paper, steel, or silicone, have been destroyed along with them. We are living in the age of delusion, in which we believe in the sanctity of our recorded history—either self-scribbled or captured by another.

History is a story of discontinuous events—events that collide like weather systems or galaxies, having barely understood origins, and even less decipherable records. All the witnesses were destroyed in the collision. What they saw, what they thought, and what they felt—even if they recorded their observations on stone, paper, steel, or silicone, have been destroyed along with them. We are living in the age of delusion, in which we believe in the sanctity of our recorded history—either self-scribbled or captured by another. Second, in the musical Hamilton (which was also part of this trip to London), the character of George Washington warns Hamilton that we do not control who writes our stories. He’s telling this to a man who believes in his power to literally write his own story—and to use his words to cement his reality. He can’t—and doesn’t. His wife, Eliza, sends his legacy forward—and Lin Manuel Miranda brings us her legacy. But, as Miranda admits in interviews, even this moment for Hamilton—and therefore, for him as well—is provisional and subject to changing tastes and critical opinion.

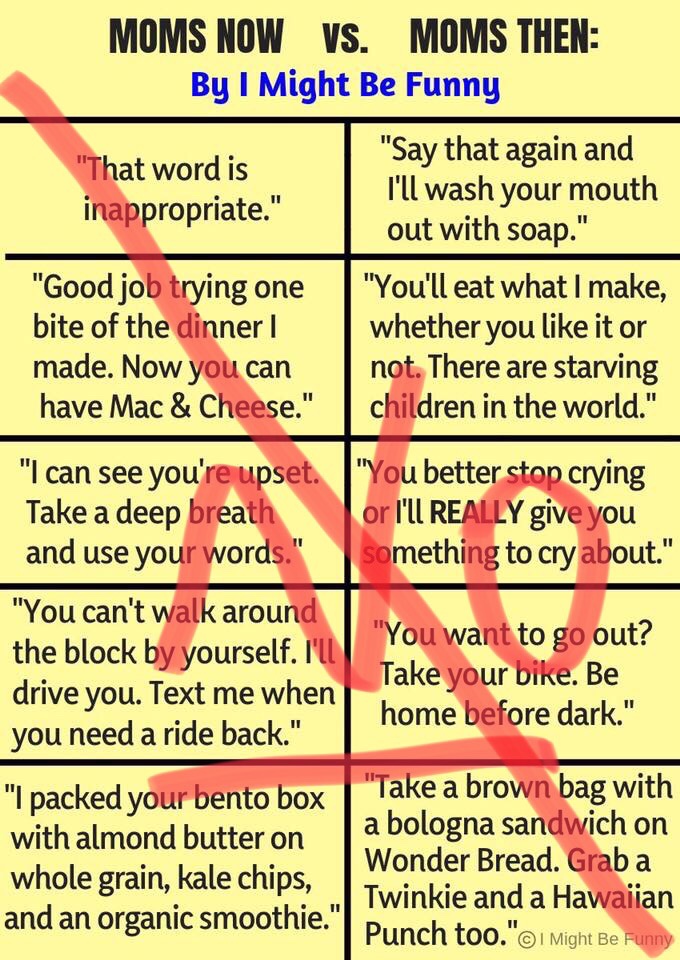

Second, in the musical Hamilton (which was also part of this trip to London), the character of George Washington warns Hamilton that we do not control who writes our stories. He’s telling this to a man who believes in his power to literally write his own story—and to use his words to cement his reality. He can’t—and doesn’t. His wife, Eliza, sends his legacy forward—and Lin Manuel Miranda brings us her legacy. But, as Miranda admits in interviews, even this moment for Hamilton—and therefore, for him as well—is provisional and subject to changing tastes and critical opinion. A current meme on Facebook compares what Moms used to say to their kids with what they say now. It is held up as a clarion call to the virtues of yesteryear, when Moms—and their kids—knew what was what. Over and over again, stuff (stuff) like this careens around the internet, in casual banter on news shows, in conversations in my workplaces. Those of us who grew up in the mythical “then” look back with nostalgia, and look at this moment with a jocular disdain. I would like to call “bullshit” on the whole enterprise.

A current meme on Facebook compares what Moms used to say to their kids with what they say now. It is held up as a clarion call to the virtues of yesteryear, when Moms—and their kids—knew what was what. Over and over again, stuff (stuff) like this careens around the internet, in casual banter on news shows, in conversations in my workplaces. Those of us who grew up in the mythical “then” look back with nostalgia, and look at this moment with a jocular disdain. I would like to call “bullshit” on the whole enterprise. My mother did what she thought and felt was right. She learned her lessons from her mother and family—and what lessons they were. Some things, she changed. She never leashed us to trees in the front yard. Others were more indelible. I am certain that most of us parent in the same way—sifting through the conscious and unconscious lessons that we received from our parents. What we do, we do almost on a kind of autopilot—in the heat of the moment, dumb memory takes over. Change is hard.

My mother did what she thought and felt was right. She learned her lessons from her mother and family—and what lessons they were. Some things, she changed. She never leashed us to trees in the front yard. Others were more indelible. I am certain that most of us parent in the same way—sifting through the conscious and unconscious lessons that we received from our parents. What we do, we do almost on a kind of autopilot—in the heat of the moment, dumb memory takes over. Change is hard. Is there anything worse than being mis-known? Than someone making a claim about how you feel or think that has almost nothing to do with your actual thoughts or feelings? I remember an occasion after one of our Thursday night poker games in Binghamton when some poor soul ventured that no matter what I said, he knew that what I felt in my heart was different. I don’t even remember what we were discussing—maybe Moby Dick. My friend Brian looked at me at that moment, acknowledging the serious breach that had been made.

Is there anything worse than being mis-known? Than someone making a claim about how you feel or think that has almost nothing to do with your actual thoughts or feelings? I remember an occasion after one of our Thursday night poker games in Binghamton when some poor soul ventured that no matter what I said, he knew that what I felt in my heart was different. I don’t even remember what we were discussing—maybe Moby Dick. My friend Brian looked at me at that moment, acknowledging the serious breach that had been made.