Howl, howl, howl, howl! O, you are men of stones:

Had I your tongues and eyes, I’ld use them so

That heaven’s vault should crack.

King Lear V.III

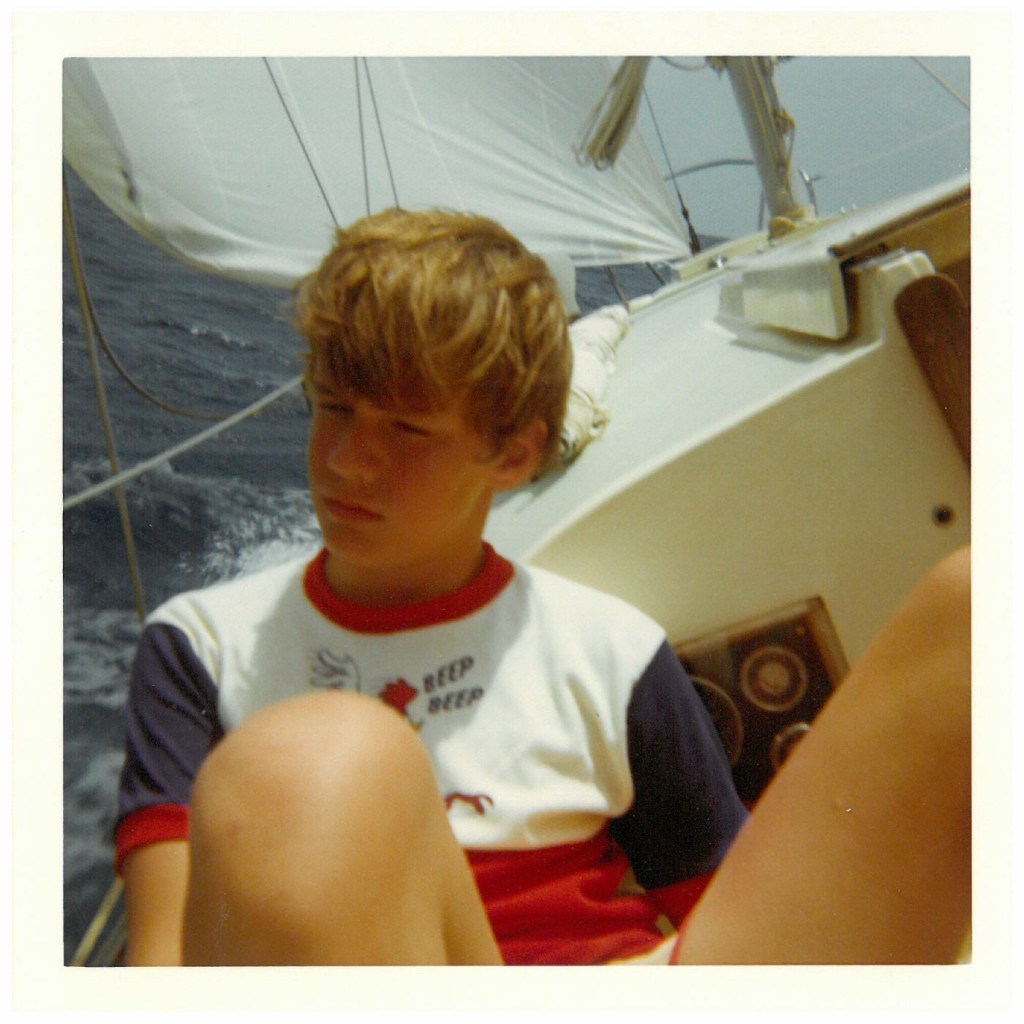

My father and I traded knowing looks when one of our crewmates complained about the weather. Anyone who heads out onto the ocean for anything more than a day sail should understand that the weather will change and, then, change again.

There is nothing a sailor can do to change the weather. You can alter course when conditions make the way forward nonsensically impassable. You should. Otherwise, onward.

That said, there are days on the ocean when all you want is weather of any sort, when the sea is glassy in every direction, and the horizon is a long uninterrupted line in the distance. The only wind blows in your memory, and even there, it is nothing more than a hot, lazy zephyr. If you chose to complain, your voice would rise only up to an endless and cloudless blue sky.

If you sail to find perfect weather, you waste your effort. Each day—whether bound with boredom or rapt with terror—is a test to match intention (your course) to the conditions. If you really are a sailor, the weather is always already perfect—such as it is. The same holds true for your vessel: the quality of your sails, the weight of your keel, the hull speed. Once you take the helm, you—your intentions, your ability, your fitness–are the only genuine, imperfect variable.

Complaint becomes, therefore, a reflection of the one thing that you can change: yourself.

When Lear unleashes his “Howl,” it demonstrates the dissonance between his internal state—his intellect and emotions—and the external state. He seeks to crack the vault of heaven not only to mourn Cordelia but because Cordelia died as a result of his inability to match his intentions to the world around him. He rails against God because he cannot reconcile the failure of his plan.

So too, the sailor who complains, “The rain sucks.” Or, “I hate this rain.” No, it’s not quite a “howl,” but what that sailor really means is that she—or he—does not like rain. The rain, in and of itself, does not suck. The lack of proper heavy weather gear sucks (Be prepared, the old Boy Scout proviso). The desire for sunny weather sucks (the Buddhist approach). The pink beaches at our destination would be better (A quick visit to the deeper tangles of Epicurus). But complaint is not grief.

When I drove home after identifying my father’s body on the dock of the Tolchester Marina, I howled in the car as I drove west over the Chesapeake Bay Bridge. It was a rainy Wednesday night, and a cat had wandered onto the dock while the emergency crew arranged his body between two pylons. They pulled the tarp back, and there he was, sodden and swollen from 36 hours in the water, and torn from where the hook found his body on the silty bottom of the boatyard.

As I drove over the bridge under which I ended my first glorious sail home—making 8 knots on a firm beam reach, nearly a perfect sail in that old Cape Dory—I let loose one long howl, holding it for the length of the span, tears flowing freely. While we, my brothers and mother, all anticipated his death, we still mourned his passing. He was, as we continued to toast him in his absence, “the founder of the feast.”

He was also, over the last decades of his life, a sailor. He had his flaws—there were times when we should not have left port, despite the sacrosanct schedule that he typed up and kept in a folder on the navigator’s desk. But who’s perfect?

We looked at each other and then turned our vision to the horizon, grey and wet in every direction—no matter where we sailed, the rain would find us. We were wet beneath our foul weather gear. What did it matter? We are made of water. We never said as much, but we knew. It was perfect.

I was not always a sailor, even though I learned when I was 11. Sailing on the Bay bored me; even the crystalline beauty of the British Virgin Islands failed to hold my attention until we dropped anchor and snorkeled our way through schools of brilliant fish and then down to fans of coral 30 feet below the surface. I did not find my way until I was in my thirties, and we were on the ocean in heavy weather. Because I am not perfect, I left those lessons on the ocean for too long. Memory is a boon and a bounty—with each remembered hurt, there is a corresponding gift.

There is a time for grief, and for some, a time for complaint. For sailors, once the course has been settled, there is only the sail and a wish for steady wind. And then, an acceptance of whatever comes. There will be howls.

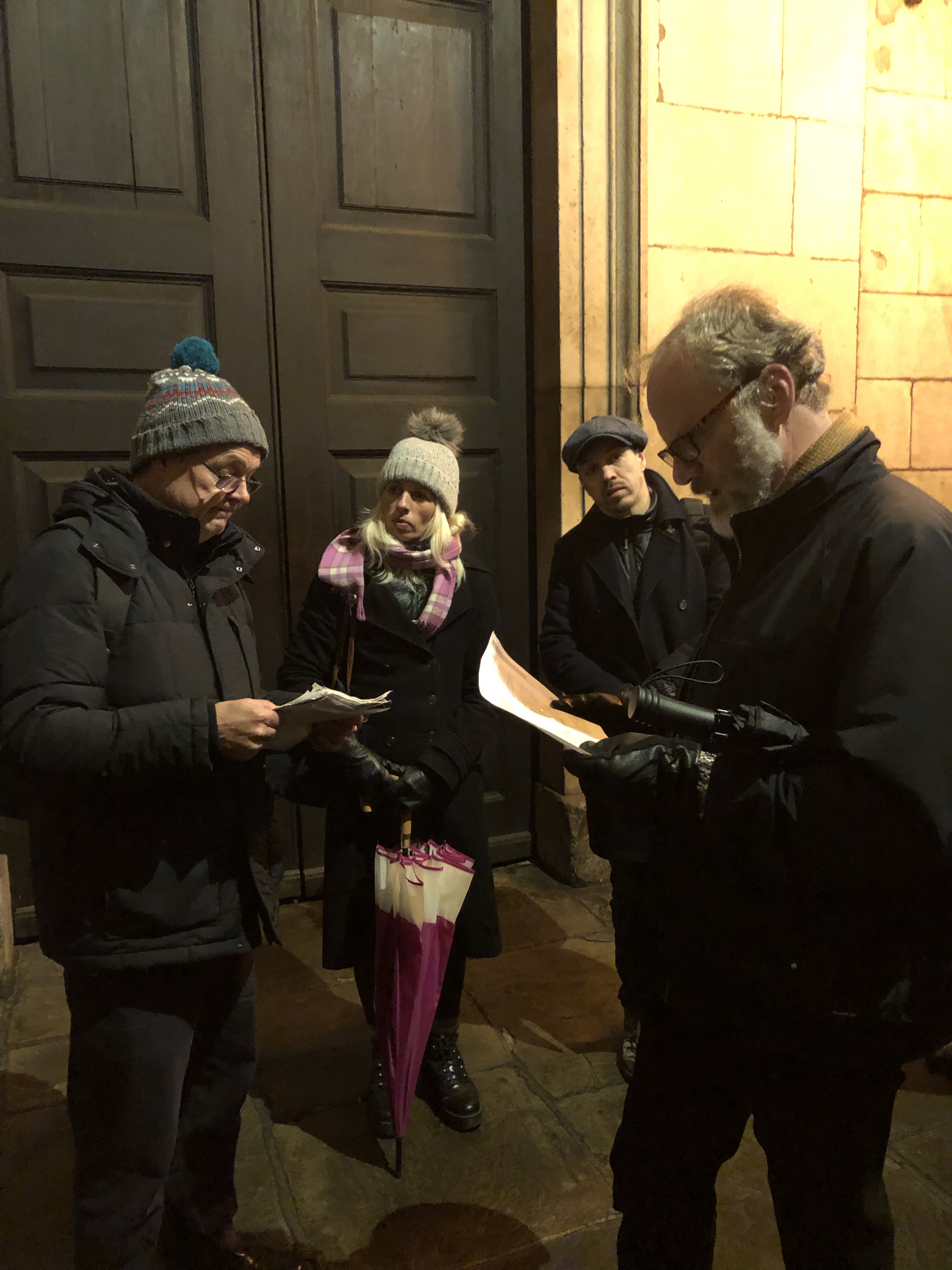

It has been a year and a few months since I was in London. I’m thinking about London while I sit and study Monet’s “Houses of Parliament, Sunset” at the National Gallery of Art. The memory of looking across the Thames at that building, with Big Ben swathed in the latticework of repair, has faded only a little. The memories of walking the streets of the original square mile and beyond remain startlingly vivid. I used them to paint scenes when the characters in my novel walked through London. The memories of the places and the memories of the feelings.

It has been a year and a few months since I was in London. I’m thinking about London while I sit and study Monet’s “Houses of Parliament, Sunset” at the National Gallery of Art. The memory of looking across the Thames at that building, with Big Ben swathed in the latticework of repair, has faded only a little. The memories of walking the streets of the original square mile and beyond remain startlingly vivid. I used them to paint scenes when the characters in my novel walked through London. The memories of the places and the memories of the feelings. When I was last in London, I was taking steps into a world where I knew I could live, where I had longed to live. Just like in the dream, writing—flight—was not foreign to me, but something I had traded in for a more certain, more directed existence. While “You are…You should” can feel like shackles, flying—writing—is formless and uncertain. Anywhere is possible. Everywhere is almost a mandate. Just like in the dream, I had written before—had flown—and had lived closer to the limits of my existence. But I had to leave my self-imposed limits. I had to accept that I might fall—and fail—but just as I accepted that in my dream—soaring up the side of a steel and glass edifice, wondering, “What if I forget? What if I fall?—I thought, even as the thrill of fear invigorated me, “You are flying now. Even if you fall, you will remember as you fall, and fly again. Keep flying.”

When I was last in London, I was taking steps into a world where I knew I could live, where I had longed to live. Just like in the dream, writing—flight—was not foreign to me, but something I had traded in for a more certain, more directed existence. While “You are…You should” can feel like shackles, flying—writing—is formless and uncertain. Anywhere is possible. Everywhere is almost a mandate. Just like in the dream, I had written before—had flown—and had lived closer to the limits of my existence. But I had to leave my self-imposed limits. I had to accept that I might fall—and fail—but just as I accepted that in my dream—soaring up the side of a steel and glass edifice, wondering, “What if I forget? What if I fall?—I thought, even as the thrill of fear invigorated me, “You are flying now. Even if you fall, you will remember as you fall, and fly again. Keep flying.” Two women look at the Monet—taking seat in the National Gallery beside me. They think it is beautiful, but claim, “It doesn’t look like that.” Of course, the Houses of Parliament look like that, as does the river Thames, as does the sunset. “We didn’t see it,” they claim, “We were tourists, doing touristy things, like thinking about where to have dinner.” I did not think about dinner when I was in London. As much as I love dinner, even food became a secondary thought while I was in London. Even the pubs and ales became little more than way-stations along the bigger task—the journey, the seeing, the walking, and the flying. And the writing.

Two women look at the Monet—taking seat in the National Gallery beside me. They think it is beautiful, but claim, “It doesn’t look like that.” Of course, the Houses of Parliament look like that, as does the river Thames, as does the sunset. “We didn’t see it,” they claim, “We were tourists, doing touristy things, like thinking about where to have dinner.” I did not think about dinner when I was in London. As much as I love dinner, even food became a secondary thought while I was in London. Even the pubs and ales became little more than way-stations along the bigger task—the journey, the seeing, the walking, and the flying. And the writing.

In the other corner of the Freer Gallery, an exhibit of Hokusai’s paintings and illustrations includes quotations from the artist about what he intended—not just in the specific works, but as an artist. He wrote about discovering himself as an artist late in life. He was already an artist, but he claims to come into his own in his 50s and thought that he might attain his most complete vision if he lived to 110. He died at 90. His work is sweeping and intimate—monumental nature and quiet personal moments—fantastic and humorous—heroes wrestling demons and uproarious coworkers. Whatever else he meant to last in his work—why that hero wrestled that demon (as if one could easily answer such a question)?—he meant it to last. He aspired to capture a vision that would last long after he died.

In the other corner of the Freer Gallery, an exhibit of Hokusai’s paintings and illustrations includes quotations from the artist about what he intended—not just in the specific works, but as an artist. He wrote about discovering himself as an artist late in life. He was already an artist, but he claims to come into his own in his 50s and thought that he might attain his most complete vision if he lived to 110. He died at 90. His work is sweeping and intimate—monumental nature and quiet personal moments—fantastic and humorous—heroes wrestling demons and uproarious coworkers. Whatever else he meant to last in his work—why that hero wrestled that demon (as if one could easily answer such a question)?—he meant it to last. He aspired to capture a vision that would last long after he died.