Although it has maintained a broad appeal, telling a beautifully depicted story and asking questions about artificial intelligence and the nature of humanity in a comfortable and technologically advanced world, the second season of Westworld has been shackled by narrative devices that give it little room to move or grow. First, a signal climactic event is visited and revisited in the initial episode of the season, from which there has been no narrative space to move into. The deeper issues of how we use stories to perceive and create reality (or consciousness) have been discarded in advance of a plot driven by revenge and violence.

Although it has maintained a broad appeal, telling a beautifully depicted story and asking questions about artificial intelligence and the nature of humanity in a comfortable and technologically advanced world, the second season of Westworld has been shackled by narrative devices that give it little room to move or grow. First, a signal climactic event is visited and revisited in the initial episode of the season, from which there has been no narrative space to move into. The deeper issues of how we use stories to perceive and create reality (or consciousness) have been discarded in advance of a plot driven by revenge and violence.

The first season of Westworld displayed ample amounts of violence and sex, but seemed to be making comments on the baser human instincts that the park revealed. The characters with whom we sided—the robot hosts—were fighting to escape their loops: the repetitive cycles of abuse perpetrated on them to delight the human guests. When the first season culminated in a host revolution, the viewer could cheer, because the robots were breaking free of their loops. As the second season began, the hosts descend to violence against the humans and each other that rivals anything that occurred in the first season.

The war begins in the first episode and is shown in two closely linked timelines: one immediately following the uprising that ended season one, the other taking place a few weeks later. In the first timeline the hosts decimate the guests, in the second nearly all the hosts are found “dead” in an artificial lake. The season has been spent linking these two timelines and filling in some backstory to explain the “true” rationale for the park. We see waves of humans face the hosts, each one being dispatched with swift and stylized violence. We also watch as the hosts turn on each other. Set free from their controlled loops they repeat and amplify the excesses they had suffered as vehicles for the guests “bloody delights.”

The war begins in the first episode and is shown in two closely linked timelines: one immediately following the uprising that ended season one, the other taking place a few weeks later. In the first timeline the hosts decimate the guests, in the second nearly all the hosts are found “dead” in an artificial lake. The season has been spent linking these two timelines and filling in some backstory to explain the “true” rationale for the park. We see waves of humans face the hosts, each one being dispatched with swift and stylized violence. We also watch as the hosts turn on each other. Set free from their controlled loops they repeat and amplify the excesses they had suffered as vehicles for the guests “bloody delights.”

While the first season was unabashedly bloody it also had four major narrative strands of awakening: Dolores gained consciousness and free will; William became the “Man in Black”; Maeve gained a kind of consciousness, but on a separate and less certain course than Dolores; and Bernard had his humanity stripped from him. Each of these plots had a cumulative development: each episode moved these stories forward, and there was a distinct pleasure as we discovered the stories for ourselves. That discovery was shared by the characters as well, some with pleasure, and some without. The climax of each story—personal revelation for good or bad—mirrored the overall plot. There was simple structural pleasure to be had.

While the first season was unabashedly bloody it also had four major narrative strands of awakening: Dolores gained consciousness and free will; William became the “Man in Black”; Maeve gained a kind of consciousness, but on a separate and less certain course than Dolores; and Bernard had his humanity stripped from him. Each of these plots had a cumulative development: each episode moved these stories forward, and there was a distinct pleasure as we discovered the stories for ourselves. That discovery was shared by the characters as well, some with pleasure, and some without. The climax of each story—personal revelation for good or bad—mirrored the overall plot. There was simple structural pleasure to be had.

In the second season these four characters have remained the main focus. But now, because the climax preceded all the events to follow, the action is more repetitive. Where else is there to go after mass slaughter? The characters do not grow so much as have secrets revealed to them or new powers added to them. They are at the mercy of plot needs. When Shogun World and Raj World, or the named but unseen Pleasure Palaces are introduced they are just grim mirrors of what goes on in Westworld. When the Cradle and the deeper purpose of the park is revealed, the viewer may have been able to anticipate their existence, but both feel like sleight of hand adjuncts to a story about characters. “Look over here! Isn’t this fancy? Don’t pay attention to the repetitiveness of the story.”

In the second season these four characters have remained the main focus. But now, because the climax preceded all the events to follow, the action is more repetitive. Where else is there to go after mass slaughter? The characters do not grow so much as have secrets revealed to them or new powers added to them. They are at the mercy of plot needs. When Shogun World and Raj World, or the named but unseen Pleasure Palaces are introduced they are just grim mirrors of what goes on in Westworld. When the Cradle and the deeper purpose of the park is revealed, the viewer may have been able to anticipate their existence, but both feel like sleight of hand adjuncts to a story about characters. “Look over here! Isn’t this fancy? Don’t pay attention to the repetitiveness of the story.”

Maybe Westworld will pull out of this narrative funk—there are three episodes left in the season. How cool would it be to discover that after revenge is piled on top of revenge that some kind of peace breaks out. Imagine that: peace as a climax. Maybe it will build on the theme of the power of story that underpinned the first season, and subvert narrative expectations by inverting rising action, and we can be as surprised as William was at the end of the first season. Or maybe the next slaughter will just be bigger, more choreographed, more beautiful, and meaningless. Here’s hoping for a quick turn.

I have been thinking about feelings. Which means, of course, that I have been having them, or rather, overwhelmed by them of late. I wouldn’t bother to write about them if they were good feelings. When I am in love, I tend to write less about that feeling, in part because my need to communicate to the world is being so generously satisfied by the person I love. The feeling of being so thoroughly understood (she gets me!) is like putty in the gaps through which the words drift out (or in). The feeling of being misunderstood blows all the putty out.

I have been thinking about feelings. Which means, of course, that I have been having them, or rather, overwhelmed by them of late. I wouldn’t bother to write about them if they were good feelings. When I am in love, I tend to write less about that feeling, in part because my need to communicate to the world is being so generously satisfied by the person I love. The feeling of being so thoroughly understood (she gets me!) is like putty in the gaps through which the words drift out (or in). The feeling of being misunderstood blows all the putty out. Over twenty-five years ago I started sailing on the ocean with my father. We would leave the Chesapeake Bay in the last week of May and spend five or six days out of sight of land on the way to Bermuda. Some days the weather was lovely. I read The Pickwick Papers on deck during my first trip, lying on the cabin roof in generous sun and a steady breeze. Some days the rain found every gap in the foul weather gear, and every inch of skin wrinkled to a puckered wet mess. There were days when no wind blew, and the foul diesel exhaust clung to the boat like regret, and days when the wind blew too hard to unfurl the smallest triangle of sail.

Over twenty-five years ago I started sailing on the ocean with my father. We would leave the Chesapeake Bay in the last week of May and spend five or six days out of sight of land on the way to Bermuda. Some days the weather was lovely. I read The Pickwick Papers on deck during my first trip, lying on the cabin roof in generous sun and a steady breeze. Some days the rain found every gap in the foul weather gear, and every inch of skin wrinkled to a puckered wet mess. There were days when no wind blew, and the foul diesel exhaust clung to the boat like regret, and days when the wind blew too hard to unfurl the smallest triangle of sail. Dr. Strangelove (1964)

Dr. Strangelove (1964) pilot screaming over the countryside to deliver his payload. I had experienced the misbegotten “fairness” doctrine—just as President Muffley tries to be fair with his Russian counterpart over the hotline. I had witnessed the driven madness of conspiracy that illuminates General Ripper, and the dedication to duty that Colonel Guano defends. Dr. Strangelove’s and Major Kong’s maniacal genius and drive was often held out as a, more sanely but only just barely, goal. Only Mandrake’s befuddled competence stands out as a lone vision of something like sanity—and he is a stranger in a strange land.

pilot screaming over the countryside to deliver his payload. I had experienced the misbegotten “fairness” doctrine—just as President Muffley tries to be fair with his Russian counterpart over the hotline. I had witnessed the driven madness of conspiracy that illuminates General Ripper, and the dedication to duty that Colonel Guano defends. Dr. Strangelove’s and Major Kong’s maniacal genius and drive was often held out as a, more sanely but only just barely, goal. Only Mandrake’s befuddled competence stands out as a lone vision of something like sanity—and he is a stranger in a strange land. Thoreau wrote in Walden that “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” In the late sixties and through the seventies, I didn’t know Thoreau at all, but I was naggingly aware of another desperation: one borne of the recent history of perpetual war and nuclear weapons. Those bombs waited like an exclamation point at the end of every thought about war, from World War Two, through Korea, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and then the Vietnam War. I often wondered who the men who bore responsibility for the weapons were, and if they were anything like the all too human men in my life. There came a point—it had passed to my way of thinking—when our weapons outstripped our ability to know how to use them. Desperation—existential anxiety—was a low thrum beneath all the humor, all the politics, and all the intensity of my teen age years.

Thoreau wrote in Walden that “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” In the late sixties and through the seventies, I didn’t know Thoreau at all, but I was naggingly aware of another desperation: one borne of the recent history of perpetual war and nuclear weapons. Those bombs waited like an exclamation point at the end of every thought about war, from World War Two, through Korea, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and then the Vietnam War. I often wondered who the men who bore responsibility for the weapons were, and if they were anything like the all too human men in my life. There came a point—it had passed to my way of thinking—when our weapons outstripped our ability to know how to use them. Desperation—existential anxiety—was a low thrum beneath all the humor, all the politics, and all the intensity of my teen age years. I first saw this with my family in the den of the house on Tinkerhill Road in Phoenixville. It was a Sunday Night event movie, probably on ABC. This was also how I first saw Lawrence of Arabia and The Great Race and Ben Hur and The Ten Commandments. I later saw My Fair Lady in a theater, first at Swarthmore College on a Friday or Saturday night movie night, and later when the print had been restored, most likely at the TLA in Philadelphia. I have seen it on television several times.

I first saw this with my family in the den of the house on Tinkerhill Road in Phoenixville. It was a Sunday Night event movie, probably on ABC. This was also how I first saw Lawrence of Arabia and The Great Race and Ben Hur and The Ten Commandments. I later saw My Fair Lady in a theater, first at Swarthmore College on a Friday or Saturday night movie night, and later when the print had been restored, most likely at the TLA in Philadelphia. I have seen it on television several times. Higgins is a brilliant driven man, and he is also, what? “a bad tempered… conceited success.” He declares himself “an ordinary man,” a “very gentle man,” and a “quiet living man,” when all evidence points to the contrary. He is an idealist and a snob. He rails against “verbal class distinctions,” while living in the lap of all the benefits of his class. I was fortunate that when I first saw this, I was able to instantly recognize that Higgins was a fool, if a fool surrounded by a stultifying upper class, and a set of gender norms (I did not call them that then) that constricted his heart and mind. When he sings, “I’m an Ordinary Man” and “A Hymn to Him,” I knew he was delusional.

Higgins is a brilliant driven man, and he is also, what? “a bad tempered… conceited success.” He declares himself “an ordinary man,” a “very gentle man,” and a “quiet living man,” when all evidence points to the contrary. He is an idealist and a snob. He rails against “verbal class distinctions,” while living in the lap of all the benefits of his class. I was fortunate that when I first saw this, I was able to instantly recognize that Higgins was a fool, if a fool surrounded by a stultifying upper class, and a set of gender norms (I did not call them that then) that constricted his heart and mind. When he sings, “I’m an Ordinary Man” and “A Hymn to Him,” I knew he was delusional. and “I Could Have Danced All Night,” are genuine, human wish songs. Eliza’s vision is never in doubt in this movie. She is a “good girl,” but early on, while watching a group of older women string beans before the market opens, she realizes that they are her future, and if she wants something else, she is going to have to change. Higgins words, “I could even get her a job as a lady’s maid or a shop assistant, which requires better English,” haunt her. She goes to Higgins and undertakes the work of transformation.

and “I Could Have Danced All Night,” are genuine, human wish songs. Eliza’s vision is never in doubt in this movie. She is a “good girl,” but early on, while watching a group of older women string beans before the market opens, she realizes that they are her future, and if she wants something else, she is going to have to change. Higgins words, “I could even get her a job as a lady’s maid or a shop assistant, which requires better English,” haunt her. She goes to Higgins and undertakes the work of transformation. And now to come back to those two little men living in my brain: Higgins is not aware that he has to change (or he will lose Eliza), nor is he aware that in his vulnerability he will gain strength (Eliza’s company). How often have I had to distract my thoughtful, intellectual self to gain access to the more vulnerable feeling self? Higgins, for whatever reason, has girded himself with thought and professional aloofness. The endlessly repeated exercises with Eliza—the servants only hear “Ay not Aye”— distract Higgins, and allow something new, something finer, to flower within him. Yes of course, it’s just Eliza’s newly potent personality that finally wins him over, but the seeds took root during those exercises.

And now to come back to those two little men living in my brain: Higgins is not aware that he has to change (or he will lose Eliza), nor is he aware that in his vulnerability he will gain strength (Eliza’s company). How often have I had to distract my thoughtful, intellectual self to gain access to the more vulnerable feeling self? Higgins, for whatever reason, has girded himself with thought and professional aloofness. The endlessly repeated exercises with Eliza—the servants only hear “Ay not Aye”— distract Higgins, and allow something new, something finer, to flower within him. Yes of course, it’s just Eliza’s newly potent personality that finally wins him over, but the seeds took root during those exercises. What’s Up, Doc? (1972)

What’s Up, Doc? (1972) I’m going to cheat here a moment and compare O’Neal to the other leading men in these movies: Lemmon, Harrison, Sellers, Taylor, Finney, Scott. He is easily the most handsome, and also the least striking, which makes him nearly disappear. There’s just no way to get a grip on him—its like grabbing melted butter. Later, watching Cary Grant in the movie this was built on, Grant’s David Huxley sputters and mugs with alacrity. Bannister is simply overwhelmed—he can’t even untie his bow tie.

I’m going to cheat here a moment and compare O’Neal to the other leading men in these movies: Lemmon, Harrison, Sellers, Taylor, Finney, Scott. He is easily the most handsome, and also the least striking, which makes him nearly disappear. There’s just no way to get a grip on him—its like grabbing melted butter. Later, watching Cary Grant in the movie this was built on, Grant’s David Huxley sputters and mugs with alacrity. Bannister is simply overwhelmed—he can’t even untie his bow tie. But there’s a magic in Bannister, and that is we can easily paste our psyches’ over his, and why wouldn’t we? Because, for reasons that are passing understanding, he draws the attention and affection of Judy Maxwell. There is no moment of kindness, no flare of brilliance, nothing. She swoops down and carries him off the way the roc would snatch an elephant from a caravan. What man doesn’t want to feel the full force of hurricane Barbara? Submit.

But there’s a magic in Bannister, and that is we can easily paste our psyches’ over his, and why wouldn’t we? Because, for reasons that are passing understanding, he draws the attention and affection of Judy Maxwell. There is no moment of kindness, no flare of brilliance, nothing. She swoops down and carries him off the way the roc would snatch an elephant from a caravan. What man doesn’t want to feel the full force of hurricane Barbara? Submit. played a prostitute in Klute. Natalie Wood played a reporter in The Great Race.

played a prostitute in Klute. Natalie Wood played a reporter in The Great Race. Surely there were couples who argued (Mark and Joanna, Higgins and Eliza), but disagreements usually foreshadowed an ending–or a horrible continuing present, which anyone who sees Whose Afraid of Virginia Woolf? can tell you is worse than any ending. I never had the benefit of watching my parents fight and make up. Most of what I saw were beginnings and endings. The vast middle ground of actual life does not lend itself to popular cinema.

Surely there were couples who argued (Mark and Joanna, Higgins and Eliza), but disagreements usually foreshadowed an ending–or a horrible continuing present, which anyone who sees Whose Afraid of Virginia Woolf? can tell you is worse than any ending. I never had the benefit of watching my parents fight and make up. Most of what I saw were beginnings and endings. The vast middle ground of actual life does not lend itself to popular cinema. Have I learned? Sure. But the heart’s first lessons are intractable. The new lessons are built on strange foundations. I have become aware of them, but only in reflection. Self knowledge is like a shoe that flies in through an open window. If it fits—that is if one is sensible enough to put the left shoe on the left foot—we spend the rest of our lives looking for the other half of the pair.

Have I learned? Sure. But the heart’s first lessons are intractable. The new lessons are built on strange foundations. I have become aware of them, but only in reflection. Self knowledge is like a shoe that flies in through an open window. If it fits—that is if one is sensible enough to put the left shoe on the left foot—we spend the rest of our lives looking for the other half of the pair.

This is at once a fanciful and a grim movie. The pace is jaunty, and the editing jumps the viewer forward, back, and side to side. Janis Joplin and The Grateful Dead perform in the film. Lester creates momentary tableaux that are discordant and arresting. A happy person, well ensconced in a healthy relationship would dismiss it as an over-intellectualized and cynical film. Since, at 17, I was neither particularly happy, and never had a relationship, it struck me as a warning about what waited in adulthood, and what a horrible warning it was.

This is at once a fanciful and a grim movie. The pace is jaunty, and the editing jumps the viewer forward, back, and side to side. Janis Joplin and The Grateful Dead perform in the film. Lester creates momentary tableaux that are discordant and arresting. A happy person, well ensconced in a healthy relationship would dismiss it as an over-intellectualized and cynical film. Since, at 17, I was neither particularly happy, and never had a relationship, it struck me as a warning about what waited in adulthood, and what a horrible warning it was. perpetual theater of feelings and opinions (and by the gruesome broadcasts of news from Vietnam). Lester’s film frames these performances as shallow, even callous. When asking for help speaking with a Spanish speaking man, one cool answers, “I only know Polish.” That’s how it is: the joke’s on you.

perpetual theater of feelings and opinions (and by the gruesome broadcasts of news from Vietnam). Lester’s film frames these performances as shallow, even callous. When asking for help speaking with a Spanish speaking man, one cool answers, “I only know Polish.” That’s how it is: the joke’s on you. Petulia has a secret. She is fighting for her life. She witnessed Archie perform surgery on a small boy she and her husband became tangled up with—fixing the mess she and her husband made. Her husband abuses her. Archie is the solid, generous, and cool alternative to the privileged, abusive, and secretly volatile world she inhabits. She shows up at Archie’s bachelor apartment, bearing a tuba. Romance of a sort follows. And ends. Archie is perplexed, and then angry that Petulia stays with a man who beats her. And then knows there is nothing he can do.

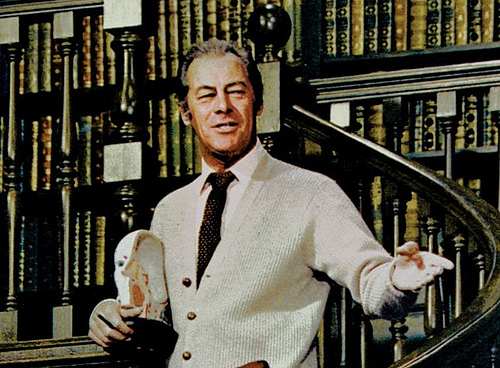

Petulia has a secret. She is fighting for her life. She witnessed Archie perform surgery on a small boy she and her husband became tangled up with—fixing the mess she and her husband made. Her husband abuses her. Archie is the solid, generous, and cool alternative to the privileged, abusive, and secretly volatile world she inhabits. She shows up at Archie’s bachelor apartment, bearing a tuba. Romance of a sort follows. And ends. Archie is perplexed, and then angry that Petulia stays with a man who beats her. And then knows there is nothing he can do. Hotel (1967)

Hotel (1967) The workaday leading man, Rod Taylor, stars as Peter McDermott, the manager of the St. Gregory Hotel. He greets people, directs personnel, plans hotel events, organizes negotiations, intercedes in disputes, and counsels the hotel’s owner. He never stops working. He knows the high society guests, the bellmen bringing room service, and the singer in the lounge. Did I briefly fantasize about working in the hotel industry? You bet.

The workaday leading man, Rod Taylor, stars as Peter McDermott, the manager of the St. Gregory Hotel. He greets people, directs personnel, plans hotel events, organizes negotiations, intercedes in disputes, and counsels the hotel’s owner. He never stops working. He knows the high society guests, the bellmen bringing room service, and the singer in the lounge. Did I briefly fantasize about working in the hotel industry? You bet. But this is about love, and Pete, so he is called by all who work with him, finds love when he woos away the French escort of the tycoon who comes to purchase the hotel. Catherine Spaak plays Jeanne, and is named in the opening titles as “The Girl From Paris” (It should be noted that Taylor is billed as “The Hotel Manager”). The tycoon introduces her as “Madame Rochefort,” but she is little more than his consort. She waits in her room of their suite while he plots the purchase and is awake for him when he finishes his business.

But this is about love, and Pete, so he is called by all who work with him, finds love when he woos away the French escort of the tycoon who comes to purchase the hotel. Catherine Spaak plays Jeanne, and is named in the opening titles as “The Girl From Paris” (It should be noted that Taylor is billed as “The Hotel Manager”). The tycoon introduces her as “Madame Rochefort,” but she is little more than his consort. She waits in her room of their suite while he plots the purchase and is awake for him when he finishes his business.