I was asked, “Do you feel old?” It was a question and an accusation.

I have reasons to be aware of my age. Over ten years ago, I had knee surgery as a result of years of overuse in swimming. My right shoulder has a tender rotator cuff; like my knees, my shoulder woes began when I was 17 and had a hitch in my freestyle stroke that put stress on the joint. Injuries never exactly go away as I am painfully reminded each time I lift weights with my hands out of a neutral position.

When I trim my beard, the hair falls from the electric razor like snow. The tide of my hairline has ebbed far enough to reveal another furrow on my brow. There are feathery lines that betray my transit. I do not always recognize the face that stares back at me, but I never truly recognized it. I have been surprising myself since before I can remember. Is that me? It is. It still is.

I know more than I did when I was 20, 30, or even 55. The accumulation of knowledge never stops. Each new day brings new articles of knowledge. I learn new ways of seeing the world or thinking about what I do. I gravitate toward books and lessons that show me something I did not know before I began. I am a specialist in my own ignorance. Every few years I feel a desire to overturn my life—uncomfortable in anything that feels like mastery, or rather, what might be mistaken for mastery. Yes, there is a value in going deep into a subject—in tunneling to the heart of a matter. But, to extend the metaphor, does the heart matter if one does not connect it to the bones and nerves and skin? What does the heart matter if it does not move out into the world and connect not just to the other 8 billion human hearts, but to everything living heart, and every other thing that does not have a heart? The more I learn, the more the connections pull at me.

I write—the single consistent strand of the past thirty-five years—because writing is not bound to any single subject. I write about movies, families, love, death, writing, baseball, anatomy, and art. I write about poems I love, and people who anger me to the point of distraction. I write about them to quell the dull ache of calcification and the even duller sense of disappointment with a world that replaces genuine surprise with momentary thrills. I write fiction and poetry to reach into the world and to describe a world that is thrilling—momentarily and for so much longer—but also deeply mysterious.

Writing is a time machine. It returns me to the giddy, carefree, and fearless time of youth. When I was ten, a flood brought the creek water a dozen feet higher than usual. The water rose above the bridge on the road below our house—a house on a hill. I went to the bridge and marveled at the swift brown water that reached the rails that spanned each side of the bridge. I waded into the water and held onto the rails. My feet lifted from the road and trailed behind me as I went hand over hand across the bridge. And once I crossed, I came back the same way.

Later in life, I did similar things, but the feeling then—water rushing past me, my feet straight out behind me, the weight of my body held by my extended arms—only fully returns when I write. And writing lets me shake off the years, not just mine, but all the years. I travel to any time I wish, unstuck from this moment, unlocked from expectation. In The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald writes about romping in the mind of God. Writing is like that. It can be. It must be.

Do I feel old? Positively. I am ancient because my writing carries me to that world—to every world. And I am young, still. Always.

I had always shrugged off the idea of traveling to the Grand Canyon. I was one of those, “what’s the big deal about a big hole in the ground” skeptics. I was wrong. Of course I was wrong. The Grand Canyon is an amazement—and of course, I was properly amazed when I saw it—looking into two billion years of rock will do that, should do that. I realized that what I had held aside was not the geology or the landscape, but the travel. Why had I discounted my ability to be amazed by travel? I had done it all my life. Going, all kinds of going, even if so much of it has been more local—on this continent, in this country—has been part of me all my life.

I had always shrugged off the idea of traveling to the Grand Canyon. I was one of those, “what’s the big deal about a big hole in the ground” skeptics. I was wrong. Of course I was wrong. The Grand Canyon is an amazement—and of course, I was properly amazed when I saw it—looking into two billion years of rock will do that, should do that. I realized that what I had held aside was not the geology or the landscape, but the travel. Why had I discounted my ability to be amazed by travel? I had done it all my life. Going, all kinds of going, even if so much of it has been more local—on this continent, in this country—has been part of me all my life. I loved airplanes and airports. Departures were invitations to new adventures. When I traveled with my family, I usually sat alone—the hazard or benefit of being an odd numbered group. I took my first plane flight alone when I went to Iowa to swim; I was 15. I traveled by train and bus alone all through my early adult life. I usually traveled to visit friends. However, I also went to cities to simply see them, to look at buildings, and camp in museums—visiting and revisiting works of art that held sway over my imagination.

I loved airplanes and airports. Departures were invitations to new adventures. When I traveled with my family, I usually sat alone—the hazard or benefit of being an odd numbered group. I took my first plane flight alone when I went to Iowa to swim; I was 15. I traveled by train and bus alone all through my early adult life. I usually traveled to visit friends. However, I also went to cities to simply see them, to look at buildings, and camp in museums—visiting and revisiting works of art that held sway over my imagination. There were trips under sail with my father and brothers. These were tests as well as trips. The ocean makes us foreign to ourselves, our bodies not made to be perpetually wet, and perpetually in motion—shaken and stirred. I have never been anywhere larger than surrounded by sky and ocean, never felt as alive, nor as alone.

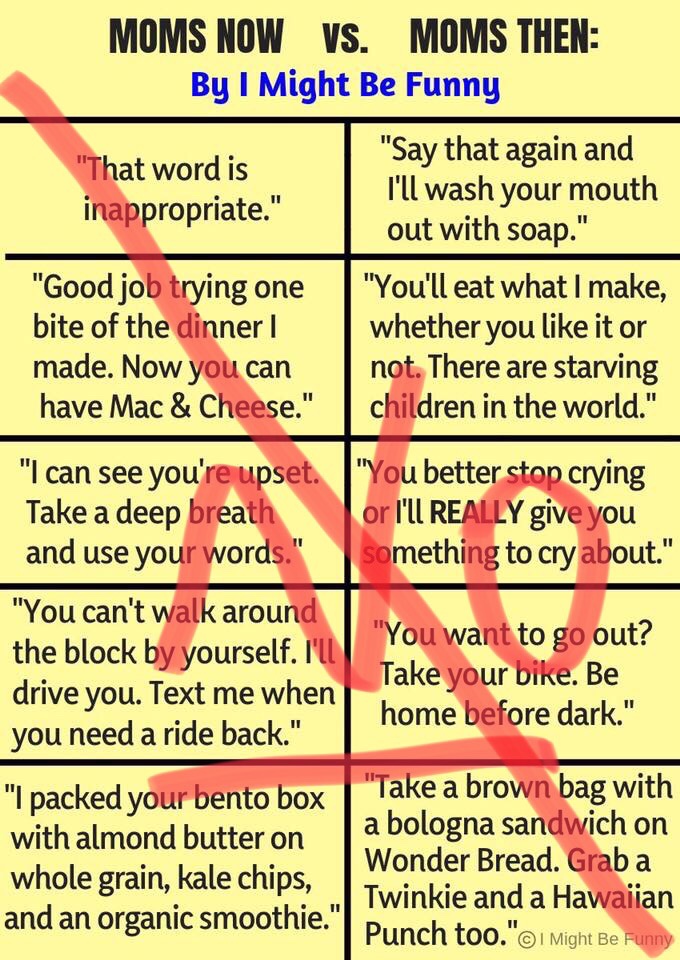

There were trips under sail with my father and brothers. These were tests as well as trips. The ocean makes us foreign to ourselves, our bodies not made to be perpetually wet, and perpetually in motion—shaken and stirred. I have never been anywhere larger than surrounded by sky and ocean, never felt as alive, nor as alone. A current meme on Facebook compares what Moms used to say to their kids with what they say now. It is held up as a clarion call to the virtues of yesteryear, when Moms—and their kids—knew what was what. Over and over again, stuff (stuff) like this careens around the internet, in casual banter on news shows, in conversations in my workplaces. Those of us who grew up in the mythical “then” look back with nostalgia, and look at this moment with a jocular disdain. I would like to call “bullshit” on the whole enterprise.

A current meme on Facebook compares what Moms used to say to their kids with what they say now. It is held up as a clarion call to the virtues of yesteryear, when Moms—and their kids—knew what was what. Over and over again, stuff (stuff) like this careens around the internet, in casual banter on news shows, in conversations in my workplaces. Those of us who grew up in the mythical “then” look back with nostalgia, and look at this moment with a jocular disdain. I would like to call “bullshit” on the whole enterprise. My mother did what she thought and felt was right. She learned her lessons from her mother and family—and what lessons they were. Some things, she changed. She never leashed us to trees in the front yard. Others were more indelible. I am certain that most of us parent in the same way—sifting through the conscious and unconscious lessons that we received from our parents. What we do, we do almost on a kind of autopilot—in the heat of the moment, dumb memory takes over. Change is hard.

My mother did what she thought and felt was right. She learned her lessons from her mother and family—and what lessons they were. Some things, she changed. She never leashed us to trees in the front yard. Others were more indelible. I am certain that most of us parent in the same way—sifting through the conscious and unconscious lessons that we received from our parents. What we do, we do almost on a kind of autopilot—in the heat of the moment, dumb memory takes over. Change is hard.