Along the way, I lost the true path. So many of these past posts have been about finding my way back to the right road—to my purpose, to writing, and to love. Like the Italian poet, I am perhaps a little attuned to an inspiring force—a Beatrice, if you will—and so as writing has come back into my life, I have found inspiration as well. But the path is writing, and I blundered off.

Dante begins The Inferno:

Midway on our life’s journey, I found myself

In dark woods, the right road lost. To tell

About those woods is hard–so tangled and rough

And savage that thinking of it now, I feel

The old fear stirring: death is hardly more bitter.

And yet, to treat the good I found there as well

I’ll tell what I saw, though how I came to enter

I cannot well say, being so full of sleep

Whatever moment it was I began to blunder

Off the true path.

Of course we ask, “Why? How?” For each of us who blundered off, the cause of our blundering was specific. Perhaps there are similarities. Here are mine.

Some of my challenge is surely due to some odd predisposition against the kind of selfish drive that must accompany the purposeful and durable impulse to write—or do anything. I recall when I was twelve or thirteen and we were electing pack leaders in my Boy Scout troop. I was nominated, and I did not vote for myself. I did not do that because I had been taught, always and hard, to think of others first, to not be selfish. I had two younger brothers—and not just younger, smaller—and was expected to make way for them, to not impose myself. Whether the overall message came from my parents, from teachers, or from some other source, I cannot say. When the time came for me to vote for a pack leader, part of being a leader, so I thought, was making the generous and considerate move. It was an early lesson.

My life in the world has set me against those who are primarily selfish. I see selfishness everywhere—the thousand daily infractions of an overarching ethical code. Be strong. Do more than your share. Tell the truth. Be kind. I do not understand behaviors that subvert those rules, and when I have broken them, or come close to breaking them, I have borne that certain weight. At some point on a dating site, there was a question, “Do you know the worst thing you have ever done?” I know the ten worst things. One was yelling at a boy with a physical disability to not block the stairs going into school. It is far from the worst. I work to balance the ledger.

I have framed the writing life, my writing life, as a calling. While that is a powerful vision of writing, a calling has its drawbacks, even dangers (see “The Dangers of a Calling“). It means that our work is not about or for us, but for something outside us, and this can lead those who live within this frame, to sacrifice, even sacrificing what is at the heart of that calling. Somewhere along the line, we must learn to be ferocious, obsessive even, about our purposes. This, and nothing else. No matter what.

Beyond that, there are many other roads, especially when one is in the dark—whether suffering through a bout of creative disconnection (no stories!), or suffering through the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune (the daily bits of life and love)—and a wrong road can seem very much like a right road. There are so many opportunities for success, and routes that promise fulfillment. The greatest dangers to purpose are not dissolution and waste; they are “almost purposeful” fulfillment. How hard to turn away from success (or the road to success) as a leader, as a teacher, as a father, as a spouse. Who would not want all these successes in his life? I am writing about me, so the male pronoun is appropriate here; I imagine that a “she” or a “they” would have the same kind of struggle.

One of the attractions of success across a broad range of fields is the push to be well-rounded. How many times was passion curtailed because it was deemed too obsessional, too blinding to a balanced life. From early on in my life, I was strongly encouraged to be conversant in several fields of study. To understand science, math, history, and, English. To be a scholar athlete. To be well-informed about the news of the day (not just local, parochial news, but in the world as well, and not just news about proto-historical events, but arts, sports, business, everything). To play a number of sports. Always more. The monomania to do the 10,000 hours of practice was seen as ungentlemanly. Me, the last amateur, breezily succeeding, breezily failing, breezily letting life slide past.

Purpose was nearly antithetical to my life. And I have paid for that. Midway on our life’s journey, I reclaim the right road. I leave these markers for you, and for me. Follow.

Almost thirty years ago, I was eating dinner at a little restaurant on the edges of Johnson City and Binghamton, New York. My mentor and her husband had invited me along. These were heady occasions, full of discussions about writing and literature, and the program in which we all worked. I was a student, but, still, I worked. On this particular occasion, they started talking about writers manqué—although I heard it as writer manqués. It was a new word for me. Manqué: having failed to become what one might have become; unfulfilled. They started listing writers who had been in the program, writers who had published and stopped, and writers who were currently in the program. It was sharp and cruel, and the sobriquet stood out as one to be avoided at all costs. These may not have been eternal footmen, but there was snickering enough to go around.

Almost thirty years ago, I was eating dinner at a little restaurant on the edges of Johnson City and Binghamton, New York. My mentor and her husband had invited me along. These were heady occasions, full of discussions about writing and literature, and the program in which we all worked. I was a student, but, still, I worked. On this particular occasion, they started talking about writers manqué—although I heard it as writer manqués. It was a new word for me. Manqué: having failed to become what one might have become; unfulfilled. They started listing writers who had been in the program, writers who had published and stopped, and writers who were currently in the program. It was sharp and cruel, and the sobriquet stood out as one to be avoided at all costs. These may not have been eternal footmen, but there was snickering enough to go around. Nonetheless, the fear of being unfulfilled lurks. In a

Nonetheless, the fear of being unfulfilled lurks. In a  I had always shrugged off the idea of traveling to the Grand Canyon. I was one of those, “what’s the big deal about a big hole in the ground” skeptics. I was wrong. Of course I was wrong. The Grand Canyon is an amazement—and of course, I was properly amazed when I saw it—looking into two billion years of rock will do that, should do that. I realized that what I had held aside was not the geology or the landscape, but the travel. Why had I discounted my ability to be amazed by travel? I had done it all my life. Going, all kinds of going, even if so much of it has been more local—on this continent, in this country—has been part of me all my life.

I had always shrugged off the idea of traveling to the Grand Canyon. I was one of those, “what’s the big deal about a big hole in the ground” skeptics. I was wrong. Of course I was wrong. The Grand Canyon is an amazement—and of course, I was properly amazed when I saw it—looking into two billion years of rock will do that, should do that. I realized that what I had held aside was not the geology or the landscape, but the travel. Why had I discounted my ability to be amazed by travel? I had done it all my life. Going, all kinds of going, even if so much of it has been more local—on this continent, in this country—has been part of me all my life. I loved airplanes and airports. Departures were invitations to new adventures. When I traveled with my family, I usually sat alone—the hazard or benefit of being an odd numbered group. I took my first plane flight alone when I went to Iowa to swim; I was 15. I traveled by train and bus alone all through my early adult life. I usually traveled to visit friends. However, I also went to cities to simply see them, to look at buildings, and camp in museums—visiting and revisiting works of art that held sway over my imagination.

I loved airplanes and airports. Departures were invitations to new adventures. When I traveled with my family, I usually sat alone—the hazard or benefit of being an odd numbered group. I took my first plane flight alone when I went to Iowa to swim; I was 15. I traveled by train and bus alone all through my early adult life. I usually traveled to visit friends. However, I also went to cities to simply see them, to look at buildings, and camp in museums—visiting and revisiting works of art that held sway over my imagination. There were trips under sail with my father and brothers. These were tests as well as trips. The ocean makes us foreign to ourselves, our bodies not made to be perpetually wet, and perpetually in motion—shaken and stirred. I have never been anywhere larger than surrounded by sky and ocean, never felt as alive, nor as alone.

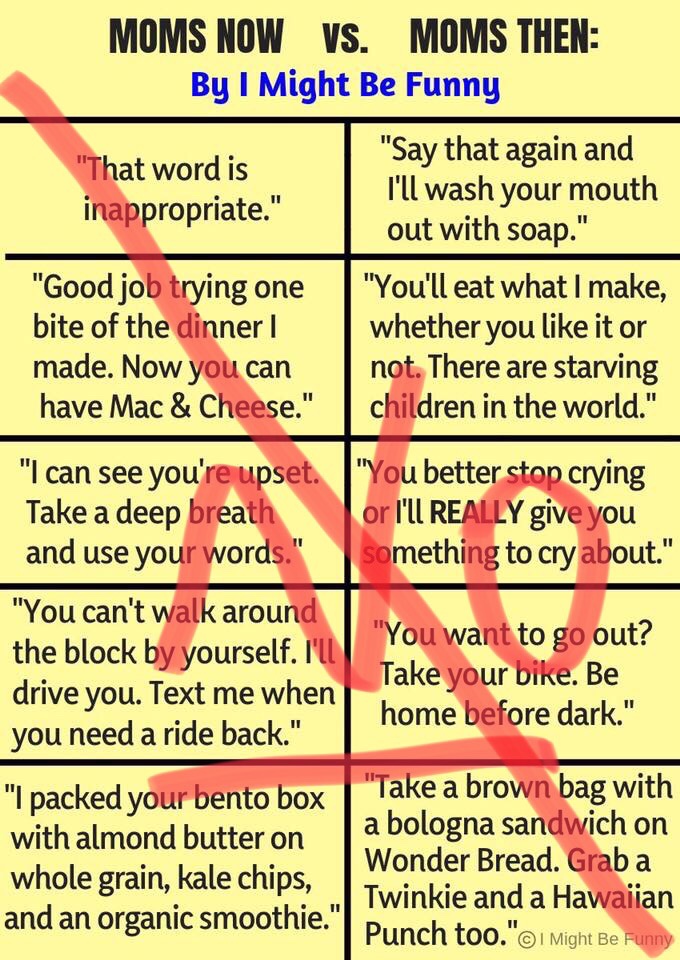

There were trips under sail with my father and brothers. These were tests as well as trips. The ocean makes us foreign to ourselves, our bodies not made to be perpetually wet, and perpetually in motion—shaken and stirred. I have never been anywhere larger than surrounded by sky and ocean, never felt as alive, nor as alone. A current meme on Facebook compares what Moms used to say to their kids with what they say now. It is held up as a clarion call to the virtues of yesteryear, when Moms—and their kids—knew what was what. Over and over again, stuff (stuff) like this careens around the internet, in casual banter on news shows, in conversations in my workplaces. Those of us who grew up in the mythical “then” look back with nostalgia, and look at this moment with a jocular disdain. I would like to call “bullshit” on the whole enterprise.

A current meme on Facebook compares what Moms used to say to their kids with what they say now. It is held up as a clarion call to the virtues of yesteryear, when Moms—and their kids—knew what was what. Over and over again, stuff (stuff) like this careens around the internet, in casual banter on news shows, in conversations in my workplaces. Those of us who grew up in the mythical “then” look back with nostalgia, and look at this moment with a jocular disdain. I would like to call “bullshit” on the whole enterprise. My mother did what she thought and felt was right. She learned her lessons from her mother and family—and what lessons they were. Some things, she changed. She never leashed us to trees in the front yard. Others were more indelible. I am certain that most of us parent in the same way—sifting through the conscious and unconscious lessons that we received from our parents. What we do, we do almost on a kind of autopilot—in the heat of the moment, dumb memory takes over. Change is hard.

My mother did what she thought and felt was right. She learned her lessons from her mother and family—and what lessons they were. Some things, she changed. She never leashed us to trees in the front yard. Others were more indelible. I am certain that most of us parent in the same way—sifting through the conscious and unconscious lessons that we received from our parents. What we do, we do almost on a kind of autopilot—in the heat of the moment, dumb memory takes over. Change is hard. I have a confession. I have a terrible time receiving love. I’m sure that this is true of almost everyone, so, I’m reluctant to make any big claim about it.

I have a confession. I have a terrible time receiving love. I’m sure that this is true of almost everyone, so, I’m reluctant to make any big claim about it. One of the questions—there are thousands of questions—on the OK Cupid dating website is:

One of the questions—there are thousands of questions—on the OK Cupid dating website is: