I have carved a method out over the several months. I am writing smaller chapters, and it seems to suit the task. Someone may correct this later, make a suggestion to combine and reorder, but for now, my brain jumps from scene to scene, from image to image, from scrap of dialogue, well you get the idea. But I have no plan, no worksheets containing outlines hung on the walls. No maps with pins tracking destinations tacked to a slanted ceiling. No scribbled notes in the margins of a dozen or two books. I have done all of those things over the past twenty years. And not written. I am working without a plan.

This method requires trust. First, and foremost, that I will continue every day, no matter what. I have done plenty of things every day over the past twenty years, but never my work, always someone else’s work, and often done with their idea of what I should be doing. How much does “should” become a cage, and I paced like Rilke’s Panther. I had to change my life.

Second, I have to trust the story as I write it. While I know where it will end up (provisionally), the work opens before me. The writing unlocks images and settings. As I wrote before, surprise is the generative heart of this work. But I have learned that the simple act of writing is like scraping away at the rust and dirt that covers something beautiful. All I need to do is scrape. I find this amazing.

Third, and this is related to the previous one, I have to trust my imagination. This is what I am uncovering. This is what had grown rusty. What I have uncovered isn’t exactly waiting for me, already made, it is the thing that does the making.What I am scraping away at is me, my hands, my mind, my heart, my imagination. Mostly my imagination.

And my imagination includes, as the dictum goes, everything. I went horse riding in the fall, and now there are horses, and one fabulous horse, in the book. I saw the Assyrian Lion Hunt reliefs at the British Museum, and the lions are there. A friend went to Kathmandu and heard an American band playing reggae at a bar called “Purple Haze”; that’s in there too. Patagonia? In the book. Another friend pointed out that what one of my characters was doing was a metaphor for how I felt about making up for lost time. Yes, that’s in there too.

The imagination eats all of the world and transforms it into some odd new thing. I trusted my imagination before, making up shorter pieces. But not like this. And so I scrape away, and find it, as vital as it was when I was a child and fell in love with Sinbad and the genie, which I learned was a story from Scheherazade and the Djinn. It all comes back.

Piece by piece, and like Scheherazade, I know I must keep telling this stories, and trust to make it through another day. The alternative is most unfortunate, but even that will be a surprise.

Almost thirty years ago, I was eating dinner at a little restaurant on the edges of Johnson City and Binghamton, New York. My mentor and her husband had invited me along. These were heady occasions, full of discussions about writing and literature, and the program in which we all worked. I was a student, but, still, I worked. On this particular occasion, they started talking about writers manqué—although I heard it as writer manqués. It was a new word for me. Manqué: having failed to become what one might have become; unfulfilled. They started listing writers who had been in the program, writers who had published and stopped, and writers who were currently in the program. It was sharp and cruel, and the sobriquet stood out as one to be avoided at all costs. These may not have been eternal footmen, but there was snickering enough to go around.

Almost thirty years ago, I was eating dinner at a little restaurant on the edges of Johnson City and Binghamton, New York. My mentor and her husband had invited me along. These were heady occasions, full of discussions about writing and literature, and the program in which we all worked. I was a student, but, still, I worked. On this particular occasion, they started talking about writers manqué—although I heard it as writer manqués. It was a new word for me. Manqué: having failed to become what one might have become; unfulfilled. They started listing writers who had been in the program, writers who had published and stopped, and writers who were currently in the program. It was sharp and cruel, and the sobriquet stood out as one to be avoided at all costs. These may not have been eternal footmen, but there was snickering enough to go around. Nonetheless, the fear of being unfulfilled lurks. In a

Nonetheless, the fear of being unfulfilled lurks. In a

Sing in me muse, and through me tell the story…

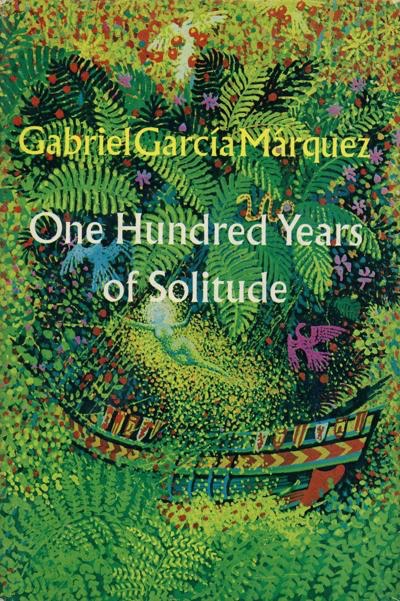

Sing in me muse, and through me tell the story… Even Gabriel Garcia Marquez, perhaps somewhat disingenuously, claimed that all the impossible elements of One Hundred Years of Solitude were true. His memoir, Living to Tell the Tale, reads like a revelation, and it makes all that seemed strange in his novel strangely normal—at least for that time and place. Of course, Marquez famously recounts the genesis of that novel—he was headed away on vacation with his family when he realized that the voice of the book was the voice of his grandmother telling incredible stories in the most matter-of-fact voice. He turned the car around and started the work that would define him as a writer. His grandmother was, in a way, his muse.

Even Gabriel Garcia Marquez, perhaps somewhat disingenuously, claimed that all the impossible elements of One Hundred Years of Solitude were true. His memoir, Living to Tell the Tale, reads like a revelation, and it makes all that seemed strange in his novel strangely normal—at least for that time and place. Of course, Marquez famously recounts the genesis of that novel—he was headed away on vacation with his family when he realized that the voice of the book was the voice of his grandmother telling incredible stories in the most matter-of-fact voice. He turned the car around and started the work that would define him as a writer. His grandmother was, in a way, his muse. While the writer uncovers the words that capture this world, she or he enters the world, and if the writer believes the words—and she must! he must!—then the inner world threatens to obliterate the outer one. After all, there is something about that outer world that the writer seeks to correct. The ghosts visit and Scrooge reforms—is literally made into someone new. This is the world that should be—where a miserly and selfish investor can become “as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world.”

While the writer uncovers the words that capture this world, she or he enters the world, and if the writer believes the words—and she must! he must!—then the inner world threatens to obliterate the outer one. After all, there is something about that outer world that the writer seeks to correct. The ghosts visit and Scrooge reforms—is literally made into someone new. This is the world that should be—where a miserly and selfish investor can become “as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world.” This past December, I traveled to a new place, London, to which I had meant to travel almost thirty years ago. I traveled after I did a series of new things, each one satisfying, but each fueling a desire for more. Almost everything that has been part of the solid ritual of my daily routine tastes bland. I don’t hanker for extremes—a solo sailing venture around the world, or an ascent up some foreboding mountain, or a year in a seraglio—I yearn to encounter something as if for the first time. I wish to be a beginner again, with a clean slate ahead of me.

This past December, I traveled to a new place, London, to which I had meant to travel almost thirty years ago. I traveled after I did a series of new things, each one satisfying, but each fueling a desire for more. Almost everything that has been part of the solid ritual of my daily routine tastes bland. I don’t hanker for extremes—a solo sailing venture around the world, or an ascent up some foreboding mountain, or a year in a seraglio—I yearn to encounter something as if for the first time. I wish to be a beginner again, with a clean slate ahead of me. The thing about writing that some people will never understand is that for the writer, it is not cerebral. Writing is physical. I feel exhausted, physically spent, after writing. Not exactly the same as after a work out, or after a night of intimacy, but I will push myself until my body shakes. I stop when I am done, when I have hit a physical limit. I do not believe that people who do not write, seriously write, understand this.

The thing about writing that some people will never understand is that for the writer, it is not cerebral. Writing is physical. I feel exhausted, physically spent, after writing. Not exactly the same as after a work out, or after a night of intimacy, but I will push myself until my body shakes. I stop when I am done, when I have hit a physical limit. I do not believe that people who do not write, seriously write, understand this.