What Transformation Means

My Fair Lady (1964)

Directed by George Cukor

Starring

Audrey Hepburn as Eliza Doolittle

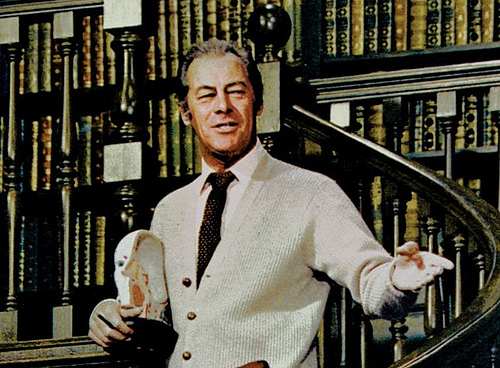

Rex Harrison as Henry Higgins

I first saw this with my family in the den of the house on Tinkerhill Road in Phoenixville. It was a Sunday Night event movie, probably on ABC. This was also how I first saw Lawrence of Arabia and The Great Race and Ben Hur and The Ten Commandments. I later saw My Fair Lady in a theater, first at Swarthmore College on a Friday or Saturday night movie night, and later when the print had been restored, most likely at the TLA in Philadelphia. I have seen it on television several times.

I first saw this with my family in the den of the house on Tinkerhill Road in Phoenixville. It was a Sunday Night event movie, probably on ABC. This was also how I first saw Lawrence of Arabia and The Great Race and Ben Hur and The Ten Commandments. I later saw My Fair Lady in a theater, first at Swarthmore College on a Friday or Saturday night movie night, and later when the print had been restored, most likely at the TLA in Philadelphia. I have seen it on television several times.

I remember looking for Pygmalion, George Bernard Shaw’s play on which the musical is based, in my school library (it wasn’t there). I looked it up over and over, as if this time it would have been added. A note that has nothing to do with anything else: I am an inveterate checker and re-checker of things. I used to call my answering machine several times; if there was a message it would pick up after two rings. I reload baseball scores and stock market indices on my cell phone with the manic fury of a dervish. I can play solitaire until the sun rises. It’s like mental chewing gum; it allows the homunculus who says “No,” to stay busy while the other dwarf imagines possibilities. Which does have something to do with My Fair Lady, after all.

Higgins is a brilliant driven man, and he is also, what? “a bad tempered… conceited success.” He declares himself “an ordinary man,” a “very gentle man,” and a “quiet living man,” when all evidence points to the contrary. He is an idealist and a snob. He rails against “verbal class distinctions,” while living in the lap of all the benefits of his class. I was fortunate that when I first saw this, I was able to instantly recognize that Higgins was a fool, if a fool surrounded by a stultifying upper class, and a set of gender norms (I did not call them that then) that constricted his heart and mind. When he sings, “I’m an Ordinary Man” and “A Hymn to Him,” I knew he was delusional.

Higgins is a brilliant driven man, and he is also, what? “a bad tempered… conceited success.” He declares himself “an ordinary man,” a “very gentle man,” and a “quiet living man,” when all evidence points to the contrary. He is an idealist and a snob. He rails against “verbal class distinctions,” while living in the lap of all the benefits of his class. I was fortunate that when I first saw this, I was able to instantly recognize that Higgins was a fool, if a fool surrounded by a stultifying upper class, and a set of gender norms (I did not call them that then) that constricted his heart and mind. When he sings, “I’m an Ordinary Man” and “A Hymn to Him,” I knew he was delusional.

By comparison, Eliza’s songs are full of hope for connection. “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly,”  and “I Could Have Danced All Night,” are genuine, human wish songs. Eliza’s vision is never in doubt in this movie. She is a “good girl,” but early on, while watching a group of older women string beans before the market opens, she realizes that they are her future, and if she wants something else, she is going to have to change. Higgins words, “I could even get her a job as a lady’s maid or a shop assistant, which requires better English,” haunt her. She goes to Higgins and undertakes the work of transformation.

and “I Could Have Danced All Night,” are genuine, human wish songs. Eliza’s vision is never in doubt in this movie. She is a “good girl,” but early on, while watching a group of older women string beans before the market opens, she realizes that they are her future, and if she wants something else, she is going to have to change. Higgins words, “I could even get her a job as a lady’s maid or a shop assistant, which requires better English,” haunt her. She goes to Higgins and undertakes the work of transformation.

Eliza and Higgins (and Colonel Pickering, charmingly played by Wilfrid Hyde-White) get the project underway. There are predictable challenges (“Just You Wait”), bumps (Ascot), and the eventual success (“You Did It!”), but the story is not about Eliza’s transformation. Of course, the story is about Eliza’s transformation, but it’s not about her learning to speak English well enough to masquerade as royalty at the Embassy Ball, or even speak well enough to work as a shop assistant. Eliza learns her value, and she learns that value is not determined by the upper, middle, or lower-class morality, but by something more transcendent—something more ideal, platonic, “friendly-like.”

Did I know that part when I was 14 or 15? No, I might have sensed it, but most likely it swam away from me. What I did know was that Higgins had to change. He could not remain aloof and professionally disdainful of the world–an intellectual bully–but had to accept that deep personal connection was not only possible, but necessary. Eliza cracks his shell. She sees him bereft of her presence, and he knows that she has seen him in this vulnerable state. He may not change his affect, but they will always know it is a front.

Whether or not they form a romantic attachment, they have become true partners, because he has shown her his vulnerability. She will become his secret keeper (He is human and flawed), and she will also become his protégé and heir, and better than he was because her experiences have been more galvanizing. I knew that was what partnership was meant to be, and recognized that change only came when a personal cord was struck.

And now to come back to those two little men living in my brain: Higgins is not aware that he has to change (or he will lose Eliza), nor is he aware that in his vulnerability he will gain strength (Eliza’s company). How often have I had to distract my thoughtful, intellectual self to gain access to the more vulnerable feeling self? Higgins, for whatever reason, has girded himself with thought and professional aloofness. The endlessly repeated exercises with Eliza—the servants only hear “Ay not Aye”— distract Higgins, and allow something new, something finer, to flower within him. Yes of course, it’s just Eliza’s newly potent personality that finally wins him over, but the seeds took root during those exercises.

And now to come back to those two little men living in my brain: Higgins is not aware that he has to change (or he will lose Eliza), nor is he aware that in his vulnerability he will gain strength (Eliza’s company). How often have I had to distract my thoughtful, intellectual self to gain access to the more vulnerable feeling self? Higgins, for whatever reason, has girded himself with thought and professional aloofness. The endlessly repeated exercises with Eliza—the servants only hear “Ay not Aye”— distract Higgins, and allow something new, something finer, to flower within him. Yes of course, it’s just Eliza’s newly potent personality that finally wins him over, but the seeds took root during those exercises.

Did I play solitaire until the sun rose because I knew it would distract my thinking brain, and help me “feel”? No. It’s just what happened—over years, not the six months that Higgins had with Eliza. Maybe what I needed was an “Eliza.” Or a household of servants. 40 more years certainly did not hurt.

What’s Up, Doc? (1972)

What’s Up, Doc? (1972) I’m going to cheat here a moment and compare O’Neal to the other leading men in these movies: Lemmon, Harrison, Sellers, Taylor, Finney, Scott. He is easily the most handsome, and also the least striking, which makes him nearly disappear. There’s just no way to get a grip on him—its like grabbing melted butter. Later, watching Cary Grant in the movie this was built on, Grant’s David Huxley sputters and mugs with alacrity. Bannister is simply overwhelmed—he can’t even untie his bow tie.

I’m going to cheat here a moment and compare O’Neal to the other leading men in these movies: Lemmon, Harrison, Sellers, Taylor, Finney, Scott. He is easily the most handsome, and also the least striking, which makes him nearly disappear. There’s just no way to get a grip on him—its like grabbing melted butter. Later, watching Cary Grant in the movie this was built on, Grant’s David Huxley sputters and mugs with alacrity. Bannister is simply overwhelmed—he can’t even untie his bow tie. But there’s a magic in Bannister, and that is we can easily paste our psyches’ over his, and why wouldn’t we? Because, for reasons that are passing understanding, he draws the attention and affection of Judy Maxwell. There is no moment of kindness, no flare of brilliance, nothing. She swoops down and carries him off the way the roc would snatch an elephant from a caravan. What man doesn’t want to feel the full force of hurricane Barbara? Submit.

But there’s a magic in Bannister, and that is we can easily paste our psyches’ over his, and why wouldn’t we? Because, for reasons that are passing understanding, he draws the attention and affection of Judy Maxwell. There is no moment of kindness, no flare of brilliance, nothing. She swoops down and carries him off the way the roc would snatch an elephant from a caravan. What man doesn’t want to feel the full force of hurricane Barbara? Submit. played a prostitute in Klute. Natalie Wood played a reporter in The Great Race.

played a prostitute in Klute. Natalie Wood played a reporter in The Great Race. Surely there were couples who argued (Mark and Joanna, Higgins and Eliza), but disagreements usually foreshadowed an ending–or a horrible continuing present, which anyone who sees Whose Afraid of Virginia Woolf? can tell you is worse than any ending. I never had the benefit of watching my parents fight and make up. Most of what I saw were beginnings and endings. The vast middle ground of actual life does not lend itself to popular cinema.

Surely there were couples who argued (Mark and Joanna, Higgins and Eliza), but disagreements usually foreshadowed an ending–or a horrible continuing present, which anyone who sees Whose Afraid of Virginia Woolf? can tell you is worse than any ending. I never had the benefit of watching my parents fight and make up. Most of what I saw were beginnings and endings. The vast middle ground of actual life does not lend itself to popular cinema. Have I learned? Sure. But the heart’s first lessons are intractable. The new lessons are built on strange foundations. I have become aware of them, but only in reflection. Self knowledge is like a shoe that flies in through an open window. If it fits—that is if one is sensible enough to put the left shoe on the left foot—we spend the rest of our lives looking for the other half of the pair.

Have I learned? Sure. But the heart’s first lessons are intractable. The new lessons are built on strange foundations. I have become aware of them, but only in reflection. Self knowledge is like a shoe that flies in through an open window. If it fits—that is if one is sensible enough to put the left shoe on the left foot—we spend the rest of our lives looking for the other half of the pair.

This is at once a fanciful and a grim movie. The pace is jaunty, and the editing jumps the viewer forward, back, and side to side. Janis Joplin and The Grateful Dead perform in the film. Lester creates momentary tableaux that are discordant and arresting. A happy person, well ensconced in a healthy relationship would dismiss it as an over-intellectualized and cynical film. Since, at 17, I was neither particularly happy, and never had a relationship, it struck me as a warning about what waited in adulthood, and what a horrible warning it was.

This is at once a fanciful and a grim movie. The pace is jaunty, and the editing jumps the viewer forward, back, and side to side. Janis Joplin and The Grateful Dead perform in the film. Lester creates momentary tableaux that are discordant and arresting. A happy person, well ensconced in a healthy relationship would dismiss it as an over-intellectualized and cynical film. Since, at 17, I was neither particularly happy, and never had a relationship, it struck me as a warning about what waited in adulthood, and what a horrible warning it was. perpetual theater of feelings and opinions (and by the gruesome broadcasts of news from Vietnam). Lester’s film frames these performances as shallow, even callous. When asking for help speaking with a Spanish speaking man, one cool answers, “I only know Polish.” That’s how it is: the joke’s on you.

perpetual theater of feelings and opinions (and by the gruesome broadcasts of news from Vietnam). Lester’s film frames these performances as shallow, even callous. When asking for help speaking with a Spanish speaking man, one cool answers, “I only know Polish.” That’s how it is: the joke’s on you. Petulia has a secret. She is fighting for her life. She witnessed Archie perform surgery on a small boy she and her husband became tangled up with—fixing the mess she and her husband made. Her husband abuses her. Archie is the solid, generous, and cool alternative to the privileged, abusive, and secretly volatile world she inhabits. She shows up at Archie’s bachelor apartment, bearing a tuba. Romance of a sort follows. And ends. Archie is perplexed, and then angry that Petulia stays with a man who beats her. And then knows there is nothing he can do.

Petulia has a secret. She is fighting for her life. She witnessed Archie perform surgery on a small boy she and her husband became tangled up with—fixing the mess she and her husband made. Her husband abuses her. Archie is the solid, generous, and cool alternative to the privileged, abusive, and secretly volatile world she inhabits. She shows up at Archie’s bachelor apartment, bearing a tuba. Romance of a sort follows. And ends. Archie is perplexed, and then angry that Petulia stays with a man who beats her. And then knows there is nothing he can do. Hotel (1967)

Hotel (1967) The workaday leading man, Rod Taylor, stars as Peter McDermott, the manager of the St. Gregory Hotel. He greets people, directs personnel, plans hotel events, organizes negotiations, intercedes in disputes, and counsels the hotel’s owner. He never stops working. He knows the high society guests, the bellmen bringing room service, and the singer in the lounge. Did I briefly fantasize about working in the hotel industry? You bet.

The workaday leading man, Rod Taylor, stars as Peter McDermott, the manager of the St. Gregory Hotel. He greets people, directs personnel, plans hotel events, organizes negotiations, intercedes in disputes, and counsels the hotel’s owner. He never stops working. He knows the high society guests, the bellmen bringing room service, and the singer in the lounge. Did I briefly fantasize about working in the hotel industry? You bet. But this is about love, and Pete, so he is called by all who work with him, finds love when he woos away the French escort of the tycoon who comes to purchase the hotel. Catherine Spaak plays Jeanne, and is named in the opening titles as “The Girl From Paris” (It should be noted that Taylor is billed as “The Hotel Manager”). The tycoon introduces her as “Madame Rochefort,” but she is little more than his consort. She waits in her room of their suite while he plots the purchase and is awake for him when he finishes his business.

But this is about love, and Pete, so he is called by all who work with him, finds love when he woos away the French escort of the tycoon who comes to purchase the hotel. Catherine Spaak plays Jeanne, and is named in the opening titles as “The Girl From Paris” (It should be noted that Taylor is billed as “The Hotel Manager”). The tycoon introduces her as “Madame Rochefort,” but she is little more than his consort. She waits in her room of their suite while he plots the purchase and is awake for him when he finishes his business. I had that dream again.

I had that dream again. Two for the Road (1967)

Two for the Road (1967) out, an she played a character who ages from about 20 to 30. Finney is meant to be older than her and was 7 years her junior. Besides the simple matter of years, her transformation is the more amazing of the two. She is both more hopeful and more sad over the course of her character’s aging. Finney remains more static, which is one facet of his masculine character.

out, an she played a character who ages from about 20 to 30. Finney is meant to be older than her and was 7 years her junior. Besides the simple matter of years, her transformation is the more amazing of the two. She is both more hopeful and more sad over the course of her character’s aging. Finney remains more static, which is one facet of his masculine character. At the beginning of Two for the Road the Wallaces, now ten years into their marriage, drive past a bride and groom in a car after their wedding ceremony. “They don’t look very happy,” Joanna remarks. “Why should they? They just got married,” Mark answers. The movie dances through their relationship, specifically tracing a series of five car trips through the French countryside as they travel from the north to the south of France. Their banter is breezy, charming, sarcastic, and bitter, building to crescendos of “I love you” before tumbling back into doubt and resentment. Marriage seems like an unresolvable puzzle, especially to Mark, and toward the end of the movie he asks Joanna, “What can’t I accept?” She answers, “That we’re a fixture. That we’re married.”

At the beginning of Two for the Road the Wallaces, now ten years into their marriage, drive past a bride and groom in a car after their wedding ceremony. “They don’t look very happy,” Joanna remarks. “Why should they? They just got married,” Mark answers. The movie dances through their relationship, specifically tracing a series of five car trips through the French countryside as they travel from the north to the south of France. Their banter is breezy, charming, sarcastic, and bitter, building to crescendos of “I love you” before tumbling back into doubt and resentment. Marriage seems like an unresolvable puzzle, especially to Mark, and toward the end of the movie he asks Joanna, “What can’t I accept?” She answers, “That we’re a fixture. That we’re married.” She captures the look at several stages of the development of Joanna’s feelings toward Mark: from naive hopefulness through the first trembling of doubt, to disdainful resignation, and finally to generous acceptance. Did I understand the complexity of her feelings? Not at all, but I recognized the continuity, and as much as the look, how could a man not want to be loved through all his difficulty.

She captures the look at several stages of the development of Joanna’s feelings toward Mark: from naive hopefulness through the first trembling of doubt, to disdainful resignation, and finally to generous acceptance. Did I understand the complexity of her feelings? Not at all, but I recognized the continuity, and as much as the look, how could a man not want to be loved through all his difficulty. At the end of the movie, Joanna tells Mark, “But at least you’re not a bad tempered, disorganized, conceited failure any more. You’re a bad tempered, disorganized, conceited success.” He isn’t angry or upset by her comment. He knows it, and ten years into their relationship, he is happy not to keep his secret from her. She is willing, even happy, to keep it with him.

At the end of the movie, Joanna tells Mark, “But at least you’re not a bad tempered, disorganized, conceited failure any more. You’re a bad tempered, disorganized, conceited success.” He isn’t angry or upset by her comment. He knows it, and ten years into their relationship, he is happy not to keep his secret from her. She is willing, even happy, to keep it with him.

Deneuve’s character, named Catherine Gunther (the boss’s wife), is sad and no longer fits in a society built on attraction and platitude. Brubaker catches her eye because he is unpolished. Even though he can be inept, he is genuine. She is convinced to give him a try when they spend a night in the company of a quirky couple, the Greenlaws, played by Myrna Loy and Charles Boyer, who live in a castle located somewhere in New York City. She tells fortunes. He practices fencing. They inspire Catherine to seek out a more enduring love. She chooses Brubaker.

Deneuve’s character, named Catherine Gunther (the boss’s wife), is sad and no longer fits in a society built on attraction and platitude. Brubaker catches her eye because he is unpolished. Even though he can be inept, he is genuine. She is convinced to give him a try when they spend a night in the company of a quirky couple, the Greenlaws, played by Myrna Loy and Charles Boyer, who live in a castle located somewhere in New York City. She tells fortunes. He practices fencing. They inspire Catherine to seek out a more enduring love. She chooses Brubaker. It should be noted that both Brubaker and Catherine are married. They leave their spouses, and the rest of their world’s behind. Ted Gunther is a smoothie who hits on other women and depends on his wife’s willingness to ignore his behavior. Sally Kellerman (an early heartthrob because of her part in a Star Trek episode) plays Brubaker’s wife Phyllis as distant and focused on her own projects. She talks at, not with, her husband and rushes off the phone to whatever actually holds her interest.

It should be noted that both Brubaker and Catherine are married. They leave their spouses, and the rest of their world’s behind. Ted Gunther is a smoothie who hits on other women and depends on his wife’s willingness to ignore his behavior. Sally Kellerman (an early heartthrob because of her part in a Star Trek episode) plays Brubaker’s wife Phyllis as distant and focused on her own projects. She talks at, not with, her husband and rushes off the phone to whatever actually holds her interest. All except for the magical Loy and Boyer, whose wealth does not stigmatize them so much as separate them from the herd. They spend the days asleep, because of all the bad things that happen in the sun. There is no explanation given for their presence, the same way that fairy godmothers have no explanation in fairy tales. I longed for quirky friends, even as a youth. My classmates talked about Happy Days and the Pittsburgh Pirates. I had other, more shadowy interests, and no one to share them with.

All except for the magical Loy and Boyer, whose wealth does not stigmatize them so much as separate them from the herd. They spend the days asleep, because of all the bad things that happen in the sun. There is no explanation given for their presence, the same way that fairy godmothers have no explanation in fairy tales. I longed for quirky friends, even as a youth. My classmates talked about Happy Days and the Pittsburgh Pirates. I had other, more shadowy interests, and no one to share them with. The April Fools implies that happiness derived from love is so rare that it will require a rule-breaking intercession to achieve it. What a strange foundation on which to build an idea of love, and at 14, that is what I was doing. And to think that a kiss ought to lead to a trip to Paris and a new life. How many kisses would come that did not bear that freight, that betrayed that wish?

The April Fools implies that happiness derived from love is so rare that it will require a rule-breaking intercession to achieve it. What a strange foundation on which to build an idea of love, and at 14, that is what I was doing. And to think that a kiss ought to lead to a trip to Paris and a new life. How many kisses would come that did not bear that freight, that betrayed that wish?

The Red Balloon to The Great Race, from The House of Frankenstein to The Trouble with Angels. I first saw Lawrence of Arabia on a 19-inch screen. I first watched the Wizard of Oz on a black and white television.

The Red Balloon to The Great Race, from The House of Frankenstein to The Trouble with Angels. I first saw Lawrence of Arabia on a 19-inch screen. I first watched the Wizard of Oz on a black and white television. Un Chien Andalou, and Birth of a Nation. Kaori Kitao used a projector to screen the films, and we watched and re-watched scenes for hours on Wednesday afternoons. Our three hour class often ran six hours.

Un Chien Andalou, and Birth of a Nation. Kaori Kitao used a projector to screen the films, and we watched and re-watched scenes for hours on Wednesday afternoons. Our three hour class often ran six hours. Mitchum, Rosalind Russell, Humphrey Bogart, Irene Dunne, Toshiro Mifune, Myrna Loy, Fred Astaire, and Charlie Chaplin.

Mitchum, Rosalind Russell, Humphrey Bogart, Irene Dunne, Toshiro Mifune, Myrna Loy, Fred Astaire, and Charlie Chaplin. My father loved movies. He shared his love of old horror movies with us, and we did watch Frankenstein and Godzilla together. Back then, Frankenstein was not played often on television, and one UHF channel featured a week of Toho giant monster films. These, along with the Wizard of Oz or Lawrence of Arabia, were event movies. I learned from watching movies that my father also had a soft spot, enjoying The Trouble with Angels and Agnes of God, but enjoying them alone and sharing his enjoyment after the fact. If I did not learn to watch movies alone from him, I certainly continued doing so, never feeling the need for company either when watching at home or in the theater.

My father loved movies. He shared his love of old horror movies with us, and we did watch Frankenstein and Godzilla together. Back then, Frankenstein was not played often on television, and one UHF channel featured a week of Toho giant monster films. These, along with the Wizard of Oz or Lawrence of Arabia, were event movies. I learned from watching movies that my father also had a soft spot, enjoying The Trouble with Angels and Agnes of God, but enjoying them alone and sharing his enjoyment after the fact. If I did not learn to watch movies alone from him, I certainly continued doing so, never feeling the need for company either when watching at home or in the theater. Are these the best depictions of love in the movies? Hardly. Nor are they the truest depictions. They simply stood out to me. Beyond that I had only two simple rules for their selection. First, I had to see each one first on television. All but one of these I watched alone the first time I saw it, with the exception being My Fair Lady, an event movie to be sure. Second I had to see each before I was 17, before I became an adult, and before I said the words “I love you” to a woman. Whether I like it or not, every time I have said those words, from the time I was 17 until now, when I am 57, “I love you” is an echo of something I saw in these films. For better and for worse.

Are these the best depictions of love in the movies? Hardly. Nor are they the truest depictions. They simply stood out to me. Beyond that I had only two simple rules for their selection. First, I had to see each one first on television. All but one of these I watched alone the first time I saw it, with the exception being My Fair Lady, an event movie to be sure. Second I had to see each before I was 17, before I became an adult, and before I said the words “I love you” to a woman. Whether I like it or not, every time I have said those words, from the time I was 17 until now, when I am 57, “I love you” is an echo of something I saw in these films. For better and for worse.