Along the way, I lost the true path. So many of these past posts have been about finding my way back to the right road—to my purpose, to writing, and to love. Like the Italian poet, I am perhaps a little attuned to an inspiring force—a Beatrice, if you will—and so as writing has come back into my life, I have found inspiration as well. But the path is writing, and I blundered off.

Dante begins The Inferno:

Midway on our life’s journey, I found myself

In dark woods, the right road lost. To tell

About those woods is hard–so tangled and rough

And savage that thinking of it now, I feel

The old fear stirring: death is hardly more bitter.

And yet, to treat the good I found there as well

I’ll tell what I saw, though how I came to enter

I cannot well say, being so full of sleep

Whatever moment it was I began to blunder

Off the true path.

Of course we ask, “Why? How?” For each of us who blundered off, the cause of our blundering was specific. Perhaps there are similarities. Here are mine.

Some of my challenge is surely due to some odd predisposition against the kind of selfish drive that must accompany the purposeful and durable impulse to write—or do anything. I recall when I was twelve or thirteen and we were electing pack leaders in my Boy Scout troop. I was nominated, and I did not vote for myself. I did not do that because I had been taught, always and hard, to think of others first, to not be selfish. I had two younger brothers—and not just younger, smaller—and was expected to make way for them, to not impose myself. Whether the overall message came from my parents, from teachers, or from some other source, I cannot say. When the time came for me to vote for a pack leader, part of being a leader, so I thought, was making the generous and considerate move. It was an early lesson.

My life in the world has set me against those who are primarily selfish. I see selfishness everywhere—the thousand daily infractions of an overarching ethical code. Be strong. Do more than your share. Tell the truth. Be kind. I do not understand behaviors that subvert those rules, and when I have broken them, or come close to breaking them, I have borne that certain weight. At some point on a dating site, there was a question, “Do you know the worst thing you have ever done?” I know the ten worst things. One was yelling at a boy with a physical disability to not block the stairs going into school. It is far from the worst. I work to balance the ledger.

I have framed the writing life, my writing life, as a calling. While that is a powerful vision of writing, a calling has its drawbacks, even dangers (see “The Dangers of a Calling“). It means that our work is not about or for us, but for something outside us, and this can lead those who live within this frame, to sacrifice, even sacrificing what is at the heart of that calling. Somewhere along the line, we must learn to be ferocious, obsessive even, about our purposes. This, and nothing else. No matter what.

Beyond that, there are many other roads, especially when one is in the dark—whether suffering through a bout of creative disconnection (no stories!), or suffering through the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune (the daily bits of life and love)—and a wrong road can seem very much like a right road. There are so many opportunities for success, and routes that promise fulfillment. The greatest dangers to purpose are not dissolution and waste; they are “almost purposeful” fulfillment. How hard to turn away from success (or the road to success) as a leader, as a teacher, as a father, as a spouse. Who would not want all these successes in his life? I am writing about me, so the male pronoun is appropriate here; I imagine that a “she” or a “they” would have the same kind of struggle.

One of the attractions of success across a broad range of fields is the push to be well-rounded. How many times was passion curtailed because it was deemed too obsessional, too blinding to a balanced life. From early on in my life, I was strongly encouraged to be conversant in several fields of study. To understand science, math, history, and, English. To be a scholar athlete. To be well-informed about the news of the day (not just local, parochial news, but in the world as well, and not just news about proto-historical events, but arts, sports, business, everything). To play a number of sports. Always more. The monomania to do the 10,000 hours of practice was seen as ungentlemanly. Me, the last amateur, breezily succeeding, breezily failing, breezily letting life slide past.

Purpose was nearly antithetical to my life. And I have paid for that. Midway on our life’s journey, I reclaim the right road. I leave these markers for you, and for me. Follow.

Almost thirty years ago, I was eating dinner at a little restaurant on the edges of Johnson City and Binghamton, New York. My mentor and her husband had invited me along. These were heady occasions, full of discussions about writing and literature, and the program in which we all worked. I was a student, but, still, I worked. On this particular occasion, they started talking about writers manqué—although I heard it as writer manqués. It was a new word for me. Manqué: having failed to become what one might have become; unfulfilled. They started listing writers who had been in the program, writers who had published and stopped, and writers who were currently in the program. It was sharp and cruel, and the sobriquet stood out as one to be avoided at all costs. These may not have been eternal footmen, but there was snickering enough to go around.

Almost thirty years ago, I was eating dinner at a little restaurant on the edges of Johnson City and Binghamton, New York. My mentor and her husband had invited me along. These were heady occasions, full of discussions about writing and literature, and the program in which we all worked. I was a student, but, still, I worked. On this particular occasion, they started talking about writers manqué—although I heard it as writer manqués. It was a new word for me. Manqué: having failed to become what one might have become; unfulfilled. They started listing writers who had been in the program, writers who had published and stopped, and writers who were currently in the program. It was sharp and cruel, and the sobriquet stood out as one to be avoided at all costs. These may not have been eternal footmen, but there was snickering enough to go around. Nonetheless, the fear of being unfulfilled lurks. In a

Nonetheless, the fear of being unfulfilled lurks. In a

Sing in me muse, and through me tell the story…

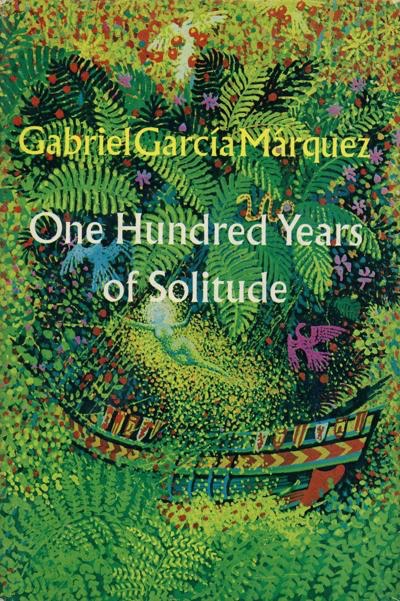

Sing in me muse, and through me tell the story… Even Gabriel Garcia Marquez, perhaps somewhat disingenuously, claimed that all the impossible elements of One Hundred Years of Solitude were true. His memoir, Living to Tell the Tale, reads like a revelation, and it makes all that seemed strange in his novel strangely normal—at least for that time and place. Of course, Marquez famously recounts the genesis of that novel—he was headed away on vacation with his family when he realized that the voice of the book was the voice of his grandmother telling incredible stories in the most matter-of-fact voice. He turned the car around and started the work that would define him as a writer. His grandmother was, in a way, his muse.

Even Gabriel Garcia Marquez, perhaps somewhat disingenuously, claimed that all the impossible elements of One Hundred Years of Solitude were true. His memoir, Living to Tell the Tale, reads like a revelation, and it makes all that seemed strange in his novel strangely normal—at least for that time and place. Of course, Marquez famously recounts the genesis of that novel—he was headed away on vacation with his family when he realized that the voice of the book was the voice of his grandmother telling incredible stories in the most matter-of-fact voice. He turned the car around and started the work that would define him as a writer. His grandmother was, in a way, his muse. While the writer uncovers the words that capture this world, she or he enters the world, and if the writer believes the words—and she must! he must!—then the inner world threatens to obliterate the outer one. After all, there is something about that outer world that the writer seeks to correct. The ghosts visit and Scrooge reforms—is literally made into someone new. This is the world that should be—where a miserly and selfish investor can become “as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world.”

While the writer uncovers the words that capture this world, she or he enters the world, and if the writer believes the words—and she must! he must!—then the inner world threatens to obliterate the outer one. After all, there is something about that outer world that the writer seeks to correct. The ghosts visit and Scrooge reforms—is literally made into someone new. This is the world that should be—where a miserly and selfish investor can become “as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world.” Is it any surprise that repetition plays a significant role in my life? I came of age as an athlete knocking out sets of 30 200 yard freestyle swims. They were yardage eaters—a quick and dirty way to lay in 6000 yards of workout and buy time for rest of the yards that the coach had in mind. We finished them at intervals of 2:30, 2:20, and 2:10, which left 50 minutes for the rest of the practice—an easy pace for the two to four thousand yards to come. Pushing off the wall every two minutes and thirty seconds, there was time for conversation between swims. Leaving at every two minutes and ten seconds put a crimp on anything other than brief exchanges: “This sucks,” “Stop hitting my feet,” “I’m hungry.”

Is it any surprise that repetition plays a significant role in my life? I came of age as an athlete knocking out sets of 30 200 yard freestyle swims. They were yardage eaters—a quick and dirty way to lay in 6000 yards of workout and buy time for rest of the yards that the coach had in mind. We finished them at intervals of 2:30, 2:20, and 2:10, which left 50 minutes for the rest of the practice—an easy pace for the two to four thousand yards to come. Pushing off the wall every two minutes and thirty seconds, there was time for conversation between swims. Leaving at every two minutes and ten seconds put a crimp on anything other than brief exchanges: “This sucks,” “Stop hitting my feet,” “I’m hungry.” This past December, I traveled to a new place, London, to which I had meant to travel almost thirty years ago. I traveled after I did a series of new things, each one satisfying, but each fueling a desire for more. Almost everything that has been part of the solid ritual of my daily routine tastes bland. I don’t hanker for extremes—a solo sailing venture around the world, or an ascent up some foreboding mountain, or a year in a seraglio—I yearn to encounter something as if for the first time. I wish to be a beginner again, with a clean slate ahead of me.

This past December, I traveled to a new place, London, to which I had meant to travel almost thirty years ago. I traveled after I did a series of new things, each one satisfying, but each fueling a desire for more. Almost everything that has been part of the solid ritual of my daily routine tastes bland. I don’t hanker for extremes—a solo sailing venture around the world, or an ascent up some foreboding mountain, or a year in a seraglio—I yearn to encounter something as if for the first time. I wish to be a beginner again, with a clean slate ahead of me. The thing about writing that some people will never understand is that for the writer, it is not cerebral. Writing is physical. I feel exhausted, physically spent, after writing. Not exactly the same as after a work out, or after a night of intimacy, but I will push myself until my body shakes. I stop when I am done, when I have hit a physical limit. I do not believe that people who do not write, seriously write, understand this.

The thing about writing that some people will never understand is that for the writer, it is not cerebral. Writing is physical. I feel exhausted, physically spent, after writing. Not exactly the same as after a work out, or after a night of intimacy, but I will push myself until my body shakes. I stop when I am done, when I have hit a physical limit. I do not believe that people who do not write, seriously write, understand this.