Dr. Strangelove (1964)

Dr. Strangelove (1964)

Directed by Stanley Kubrick

Starring

Peter Sellers as President Merkin Muffley, Group Captain Lionel Mandrake, and Dr. Strangelove

George C. Scott as General “Buck” Turgidson

Slim Pickens as Major “King” Kong

Sterling Hayden as General Jack D. Ripper

I did not see this as a Sunday night ABC Movie of the Week. This had to be a Friday night movie, starting at 11:30 or 12:00. I watched it by myself. It is a black and white movie, but I was well used to that. Almost all the horror movies of my youth were the black and white movies of Universal, or American… Besides, the first television I remember was a black and white set, which made the Wizard of Oz only a little less magical.

Why does this movie make it onto a list of movies about love? There is only one woman in the cast, Tracy Reed as General Turgidon’s “secretary,” and her part reveals more about the men than it does her. And at the end of the film, Vera Lynn sings “We’ll Meet Again” over a montage of hydrogen bomb explosions. What I didn’t know when I first saw this movie was that “We’ll Meet Again” was a soldier’s anthem in World War II; it marked the hope for those (don’t know where, don’t know when) sunny days. To me it was just dark irony.

I grew up in the company of boys. I had two younger brothers. I was in the Cub Scouts and Boy Scouts. Almost all my playmates were boys. We played “tank” on the school playground, draping our arms over each other’s shoulders and marching pointedly across the field. I went to an all boys private boarding school from 9th-12th grade. Boys playing at being men was what I knew.

Already, by my teenage years, I could see the pitfalls. I was aware of the passionate intensity that could overwhelm sensibility—just as Buck Turgidson demonstrates the the guile of a B-52 pilot screaming over the countryside to deliver his payload. I had experienced the misbegotten “fairness” doctrine—just as President Muffley tries to be fair with his Russian counterpart over the hotline. I had witnessed the driven madness of conspiracy that illuminates General Ripper, and the dedication to duty that Colonel Guano defends. Dr. Strangelove’s and Major Kong’s maniacal genius and drive was often held out as a, more sanely but only just barely, goal. Only Mandrake’s befuddled competence stands out as a lone vision of something like sanity—and he is a stranger in a strange land.

pilot screaming over the countryside to deliver his payload. I had experienced the misbegotten “fairness” doctrine—just as President Muffley tries to be fair with his Russian counterpart over the hotline. I had witnessed the driven madness of conspiracy that illuminates General Ripper, and the dedication to duty that Colonel Guano defends. Dr. Strangelove’s and Major Kong’s maniacal genius and drive was often held out as a, more sanely but only just barely, goal. Only Mandrake’s befuddled competence stands out as a lone vision of something like sanity—and he is a stranger in a strange land.

Where is the place for love—strange or otherwise—in a world that totters toward Armageddon? Romantic love is the counterpoint to the well-meaning incompetence, or belligerent dedication of the world of men. Without it: self-destruction.

Thoreau wrote in Walden that “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” In the late sixties and through the seventies, I didn’t know Thoreau at all, but I was naggingly aware of another desperation: one borne of the recent history of perpetual war and nuclear weapons. Those bombs waited like an exclamation point at the end of every thought about war, from World War Two, through Korea, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and then the Vietnam War. I often wondered who the men who bore responsibility for the weapons were, and if they were anything like the all too human men in my life. There came a point—it had passed to my way of thinking—when our weapons outstripped our ability to know how to use them. Desperation—existential anxiety—was a low thrum beneath all the humor, all the politics, and all the intensity of my teen age years.

Thoreau wrote in Walden that “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” In the late sixties and through the seventies, I didn’t know Thoreau at all, but I was naggingly aware of another desperation: one borne of the recent history of perpetual war and nuclear weapons. Those bombs waited like an exclamation point at the end of every thought about war, from World War Two, through Korea, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and then the Vietnam War. I often wondered who the men who bore responsibility for the weapons were, and if they were anything like the all too human men in my life. There came a point—it had passed to my way of thinking—when our weapons outstripped our ability to know how to use them. Desperation—existential anxiety—was a low thrum beneath all the humor, all the politics, and all the intensity of my teen age years.

And love? Could love stand against destruction? Imagine that. Only some equally powerful, equally misbegotten, equally passionate, dedicated, driven, and genius form of love, which is to say a love that was truly strange. How long would I try to fly that banner? Years.

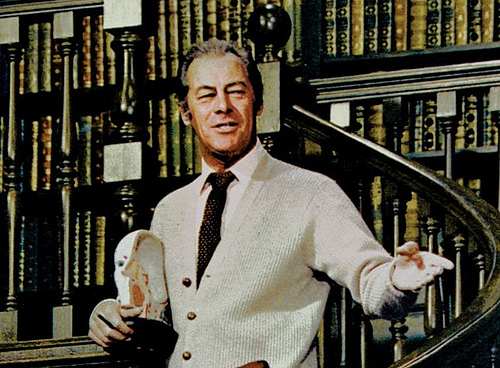

I first saw this with my family in the den of the house on Tinkerhill Road in Phoenixville. It was a Sunday Night event movie, probably on ABC. This was also how I first saw Lawrence of Arabia and The Great Race and Ben Hur and The Ten Commandments. I later saw My Fair Lady in a theater, first at Swarthmore College on a Friday or Saturday night movie night, and later when the print had been restored, most likely at the TLA in Philadelphia. I have seen it on television several times.

I first saw this with my family in the den of the house on Tinkerhill Road in Phoenixville. It was a Sunday Night event movie, probably on ABC. This was also how I first saw Lawrence of Arabia and The Great Race and Ben Hur and The Ten Commandments. I later saw My Fair Lady in a theater, first at Swarthmore College on a Friday or Saturday night movie night, and later when the print had been restored, most likely at the TLA in Philadelphia. I have seen it on television several times. Higgins is a brilliant driven man, and he is also, what? “a bad tempered… conceited success.” He declares himself “an ordinary man,” a “very gentle man,” and a “quiet living man,” when all evidence points to the contrary. He is an idealist and a snob. He rails against “verbal class distinctions,” while living in the lap of all the benefits of his class. I was fortunate that when I first saw this, I was able to instantly recognize that Higgins was a fool, if a fool surrounded by a stultifying upper class, and a set of gender norms (I did not call them that then) that constricted his heart and mind. When he sings, “I’m an Ordinary Man” and “A Hymn to Him,” I knew he was delusional.

Higgins is a brilliant driven man, and he is also, what? “a bad tempered… conceited success.” He declares himself “an ordinary man,” a “very gentle man,” and a “quiet living man,” when all evidence points to the contrary. He is an idealist and a snob. He rails against “verbal class distinctions,” while living in the lap of all the benefits of his class. I was fortunate that when I first saw this, I was able to instantly recognize that Higgins was a fool, if a fool surrounded by a stultifying upper class, and a set of gender norms (I did not call them that then) that constricted his heart and mind. When he sings, “I’m an Ordinary Man” and “A Hymn to Him,” I knew he was delusional. and “I Could Have Danced All Night,” are genuine, human wish songs. Eliza’s vision is never in doubt in this movie. She is a “good girl,” but early on, while watching a group of older women string beans before the market opens, she realizes that they are her future, and if she wants something else, she is going to have to change. Higgins words, “I could even get her a job as a lady’s maid or a shop assistant, which requires better English,” haunt her. She goes to Higgins and undertakes the work of transformation.

and “I Could Have Danced All Night,” are genuine, human wish songs. Eliza’s vision is never in doubt in this movie. She is a “good girl,” but early on, while watching a group of older women string beans before the market opens, she realizes that they are her future, and if she wants something else, she is going to have to change. Higgins words, “I could even get her a job as a lady’s maid or a shop assistant, which requires better English,” haunt her. She goes to Higgins and undertakes the work of transformation. And now to come back to those two little men living in my brain: Higgins is not aware that he has to change (or he will lose Eliza), nor is he aware that in his vulnerability he will gain strength (Eliza’s company). How often have I had to distract my thoughtful, intellectual self to gain access to the more vulnerable feeling self? Higgins, for whatever reason, has girded himself with thought and professional aloofness. The endlessly repeated exercises with Eliza—the servants only hear “Ay not Aye”— distract Higgins, and allow something new, something finer, to flower within him. Yes of course, it’s just Eliza’s newly potent personality that finally wins him over, but the seeds took root during those exercises.

And now to come back to those two little men living in my brain: Higgins is not aware that he has to change (or he will lose Eliza), nor is he aware that in his vulnerability he will gain strength (Eliza’s company). How often have I had to distract my thoughtful, intellectual self to gain access to the more vulnerable feeling self? Higgins, for whatever reason, has girded himself with thought and professional aloofness. The endlessly repeated exercises with Eliza—the servants only hear “Ay not Aye”— distract Higgins, and allow something new, something finer, to flower within him. Yes of course, it’s just Eliza’s newly potent personality that finally wins him over, but the seeds took root during those exercises. What’s Up, Doc? (1972)

What’s Up, Doc? (1972) I’m going to cheat here a moment and compare O’Neal to the other leading men in these movies: Lemmon, Harrison, Sellers, Taylor, Finney, Scott. He is easily the most handsome, and also the least striking, which makes him nearly disappear. There’s just no way to get a grip on him—its like grabbing melted butter. Later, watching Cary Grant in the movie this was built on, Grant’s David Huxley sputters and mugs with alacrity. Bannister is simply overwhelmed—he can’t even untie his bow tie.

I’m going to cheat here a moment and compare O’Neal to the other leading men in these movies: Lemmon, Harrison, Sellers, Taylor, Finney, Scott. He is easily the most handsome, and also the least striking, which makes him nearly disappear. There’s just no way to get a grip on him—its like grabbing melted butter. Later, watching Cary Grant in the movie this was built on, Grant’s David Huxley sputters and mugs with alacrity. Bannister is simply overwhelmed—he can’t even untie his bow tie. But there’s a magic in Bannister, and that is we can easily paste our psyches’ over his, and why wouldn’t we? Because, for reasons that are passing understanding, he draws the attention and affection of Judy Maxwell. There is no moment of kindness, no flare of brilliance, nothing. She swoops down and carries him off the way the roc would snatch an elephant from a caravan. What man doesn’t want to feel the full force of hurricane Barbara? Submit.

But there’s a magic in Bannister, and that is we can easily paste our psyches’ over his, and why wouldn’t we? Because, for reasons that are passing understanding, he draws the attention and affection of Judy Maxwell. There is no moment of kindness, no flare of brilliance, nothing. She swoops down and carries him off the way the roc would snatch an elephant from a caravan. What man doesn’t want to feel the full force of hurricane Barbara? Submit. played a prostitute in Klute. Natalie Wood played a reporter in The Great Race.

played a prostitute in Klute. Natalie Wood played a reporter in The Great Race. Surely there were couples who argued (Mark and Joanna, Higgins and Eliza), but disagreements usually foreshadowed an ending–or a horrible continuing present, which anyone who sees Whose Afraid of Virginia Woolf? can tell you is worse than any ending. I never had the benefit of watching my parents fight and make up. Most of what I saw were beginnings and endings. The vast middle ground of actual life does not lend itself to popular cinema.

Surely there were couples who argued (Mark and Joanna, Higgins and Eliza), but disagreements usually foreshadowed an ending–or a horrible continuing present, which anyone who sees Whose Afraid of Virginia Woolf? can tell you is worse than any ending. I never had the benefit of watching my parents fight and make up. Most of what I saw were beginnings and endings. The vast middle ground of actual life does not lend itself to popular cinema. Have I learned? Sure. But the heart’s first lessons are intractable. The new lessons are built on strange foundations. I have become aware of them, but only in reflection. Self knowledge is like a shoe that flies in through an open window. If it fits—that is if one is sensible enough to put the left shoe on the left foot—we spend the rest of our lives looking for the other half of the pair.

Have I learned? Sure. But the heart’s first lessons are intractable. The new lessons are built on strange foundations. I have become aware of them, but only in reflection. Self knowledge is like a shoe that flies in through an open window. If it fits—that is if one is sensible enough to put the left shoe on the left foot—we spend the rest of our lives looking for the other half of the pair.