Quick hot take: meh.

Positives: So much effort was made to get the visuals right, and they are crisp and awe-inspiring. However, I wondered more about the volume of computing power that made such a spectacle possible than I did about the story. Unlike the first film, in which Jake’s amazement stood in for the audience—we watched him watching this world (the scene in which he tapped all the plants—How cool!—until a vicious creature was revealed—Scary, but still cool!). There is no similar character with whom I bonded, no one whose awe provided a point of entry for mine. So yes, the movie was a visual feast, but it remained at a distance.

The addition of children and watching them as they learned how to be an adult, or warrior, or mystic (or human being because even though Cameron populates the story with Na’vi, his project is deeply humanist) provided a welcome entry point for me. It added a coming of age angle that felt more natural than Jake Sully’s man-child evolution in the first film. Perhaps Cameron believes that all men are essentially immature—it’s a common enough trope, so not a surprise, but really? Round characters, please.

Not so positives: Avatar: The Way of Water is not a complete story. It is packed with loose ends of theme and plot that do not resolve at the film’s end. A three hour movie that ends with a battle that clearly is only the opening event in a war, with an father-son conflict stretched across species and moral codes, and with such gross power imbalances between the Na’vi and humans (seriously, you watched the return of the Sky People to Pandora and didn’t think, “Well, that’s horrible, but unbeatable”?) stretches this viewer’s patience. Wrap something up, for goodness’ sake.

Who’s your daddy/mommy? Grace’s avatar was pregnant when Grace died? And so she was an immaculately conceived girl? What? And Quaritch (the bad guy) had a son? And Grace’s daughter and Quaritch’s son are in love? Is this fan fiction? Are we supposed to tune in next week—or sometime in the next three or four years to discover the answer? This is a corollary to the Chekov’s gun axiom: if you put a gun on the mantel in Act One, it better go off by Act Three; big questions asked in Act One better be answered by Act Three. Cameron may expect the audience to wait a decade, but please do something with all those loose threads.

An assortment of complaints: 1) When did Neytiri become shrill? Did motherhood change her from Jake’s patient and wise tutor to a hissing ball of rage? Or is this just a lazy “tiger mom” cliche? Maybe since Kiri seems a more complex female character, the writers did not feel compelled to make Neytiri more than a plot device (she might drown!). 2) Does Kiri have epilepsy, or a profound (and important) connection to Eywa, the pantheistic force that unites all life on Pandora? Will circumstance force her to risk her life for the greater good? Then sharpen that possibility. 3) Did we really need a Quaritch avatar/clone? While the juxtaposition of Sully and Quaritch as fathers has potential, the deus ex machina was a little too handy. I suppose if the Avengers can invent time travel to save Endgame, a memory download is not too far afield. Nonetheless, no thank you.

There’s more, and I have already spent more time on this than I originally thought I would. After over three hours in a movie theater, nearly as long as Lawrence of Arabia, at minimum I expect something more than boggling my mind about how many terabytes of computing power went into the special effects. Three hours requires story, and Avatar: The Way of Water seemed incomplete in too many ways to satisfy. Ooh ah! And not meh. Feh.

Country Living posted a

Country Living posted a  Dr. Strangelove (1964)

Dr. Strangelove (1964) pilot screaming over the countryside to deliver his payload. I had experienced the misbegotten “fairness” doctrine—just as President Muffley tries to be fair with his Russian counterpart over the hotline. I had witnessed the driven madness of conspiracy that illuminates General Ripper, and the dedication to duty that Colonel Guano defends. Dr. Strangelove’s and Major Kong’s maniacal genius and drive was often held out as a, more sanely but only just barely, goal. Only Mandrake’s befuddled competence stands out as a lone vision of something like sanity—and he is a stranger in a strange land.

pilot screaming over the countryside to deliver his payload. I had experienced the misbegotten “fairness” doctrine—just as President Muffley tries to be fair with his Russian counterpart over the hotline. I had witnessed the driven madness of conspiracy that illuminates General Ripper, and the dedication to duty that Colonel Guano defends. Dr. Strangelove’s and Major Kong’s maniacal genius and drive was often held out as a, more sanely but only just barely, goal. Only Mandrake’s befuddled competence stands out as a lone vision of something like sanity—and he is a stranger in a strange land. Thoreau wrote in Walden that “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” In the late sixties and through the seventies, I didn’t know Thoreau at all, but I was naggingly aware of another desperation: one borne of the recent history of perpetual war and nuclear weapons. Those bombs waited like an exclamation point at the end of every thought about war, from World War Two, through Korea, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and then the Vietnam War. I often wondered who the men who bore responsibility for the weapons were, and if they were anything like the all too human men in my life. There came a point—it had passed to my way of thinking—when our weapons outstripped our ability to know how to use them. Desperation—existential anxiety—was a low thrum beneath all the humor, all the politics, and all the intensity of my teen age years.

Thoreau wrote in Walden that “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” In the late sixties and through the seventies, I didn’t know Thoreau at all, but I was naggingly aware of another desperation: one borne of the recent history of perpetual war and nuclear weapons. Those bombs waited like an exclamation point at the end of every thought about war, from World War Two, through Korea, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and then the Vietnam War. I often wondered who the men who bore responsibility for the weapons were, and if they were anything like the all too human men in my life. There came a point—it had passed to my way of thinking—when our weapons outstripped our ability to know how to use them. Desperation—existential anxiety—was a low thrum beneath all the humor, all the politics, and all the intensity of my teen age years.

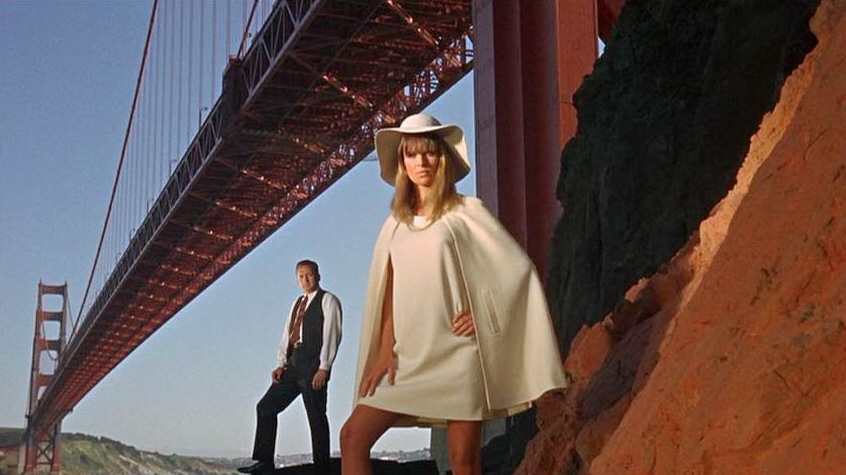

This is at once a fanciful and a grim movie. The pace is jaunty, and the editing jumps the viewer forward, back, and side to side. Janis Joplin and The Grateful Dead perform in the film. Lester creates momentary tableaux that are discordant and arresting. A happy person, well ensconced in a healthy relationship would dismiss it as an over-intellectualized and cynical film. Since, at 17, I was neither particularly happy, and never had a relationship, it struck me as a warning about what waited in adulthood, and what a horrible warning it was.

This is at once a fanciful and a grim movie. The pace is jaunty, and the editing jumps the viewer forward, back, and side to side. Janis Joplin and The Grateful Dead perform in the film. Lester creates momentary tableaux that are discordant and arresting. A happy person, well ensconced in a healthy relationship would dismiss it as an over-intellectualized and cynical film. Since, at 17, I was neither particularly happy, and never had a relationship, it struck me as a warning about what waited in adulthood, and what a horrible warning it was. perpetual theater of feelings and opinions (and by the gruesome broadcasts of news from Vietnam). Lester’s film frames these performances as shallow, even callous. When asking for help speaking with a Spanish speaking man, one cool answers, “I only know Polish.” That’s how it is: the joke’s on you.

perpetual theater of feelings and opinions (and by the gruesome broadcasts of news from Vietnam). Lester’s film frames these performances as shallow, even callous. When asking for help speaking with a Spanish speaking man, one cool answers, “I only know Polish.” That’s how it is: the joke’s on you. Petulia has a secret. She is fighting for her life. She witnessed Archie perform surgery on a small boy she and her husband became tangled up with—fixing the mess she and her husband made. Her husband abuses her. Archie is the solid, generous, and cool alternative to the privileged, abusive, and secretly volatile world she inhabits. She shows up at Archie’s bachelor apartment, bearing a tuba. Romance of a sort follows. And ends. Archie is perplexed, and then angry that Petulia stays with a man who beats her. And then knows there is nothing he can do.

Petulia has a secret. She is fighting for her life. She witnessed Archie perform surgery on a small boy she and her husband became tangled up with—fixing the mess she and her husband made. Her husband abuses her. Archie is the solid, generous, and cool alternative to the privileged, abusive, and secretly volatile world she inhabits. She shows up at Archie’s bachelor apartment, bearing a tuba. Romance of a sort follows. And ends. Archie is perplexed, and then angry that Petulia stays with a man who beats her. And then knows there is nothing he can do. Two for the Road (1967)

Two for the Road (1967) out, an she played a character who ages from about 20 to 30. Finney is meant to be older than her and was 7 years her junior. Besides the simple matter of years, her transformation is the more amazing of the two. She is both more hopeful and more sad over the course of her character’s aging. Finney remains more static, which is one facet of his masculine character.

out, an she played a character who ages from about 20 to 30. Finney is meant to be older than her and was 7 years her junior. Besides the simple matter of years, her transformation is the more amazing of the two. She is both more hopeful and more sad over the course of her character’s aging. Finney remains more static, which is one facet of his masculine character. At the beginning of Two for the Road the Wallaces, now ten years into their marriage, drive past a bride and groom in a car after their wedding ceremony. “They don’t look very happy,” Joanna remarks. “Why should they? They just got married,” Mark answers. The movie dances through their relationship, specifically tracing a series of five car trips through the French countryside as they travel from the north to the south of France. Their banter is breezy, charming, sarcastic, and bitter, building to crescendos of “I love you” before tumbling back into doubt and resentment. Marriage seems like an unresolvable puzzle, especially to Mark, and toward the end of the movie he asks Joanna, “What can’t I accept?” She answers, “That we’re a fixture. That we’re married.”

At the beginning of Two for the Road the Wallaces, now ten years into their marriage, drive past a bride and groom in a car after their wedding ceremony. “They don’t look very happy,” Joanna remarks. “Why should they? They just got married,” Mark answers. The movie dances through their relationship, specifically tracing a series of five car trips through the French countryside as they travel from the north to the south of France. Their banter is breezy, charming, sarcastic, and bitter, building to crescendos of “I love you” before tumbling back into doubt and resentment. Marriage seems like an unresolvable puzzle, especially to Mark, and toward the end of the movie he asks Joanna, “What can’t I accept?” She answers, “That we’re a fixture. That we’re married.” She captures the look at several stages of the development of Joanna’s feelings toward Mark: from naive hopefulness through the first trembling of doubt, to disdainful resignation, and finally to generous acceptance. Did I understand the complexity of her feelings? Not at all, but I recognized the continuity, and as much as the look, how could a man not want to be loved through all his difficulty.

She captures the look at several stages of the development of Joanna’s feelings toward Mark: from naive hopefulness through the first trembling of doubt, to disdainful resignation, and finally to generous acceptance. Did I understand the complexity of her feelings? Not at all, but I recognized the continuity, and as much as the look, how could a man not want to be loved through all his difficulty. At the end of the movie, Joanna tells Mark, “But at least you’re not a bad tempered, disorganized, conceited failure any more. You’re a bad tempered, disorganized, conceited success.” He isn’t angry or upset by her comment. He knows it, and ten years into their relationship, he is happy not to keep his secret from her. She is willing, even happy, to keep it with him.

At the end of the movie, Joanna tells Mark, “But at least you’re not a bad tempered, disorganized, conceited failure any more. You’re a bad tempered, disorganized, conceited success.” He isn’t angry or upset by her comment. He knows it, and ten years into their relationship, he is happy not to keep his secret from her. She is willing, even happy, to keep it with him.

Deneuve’s character, named Catherine Gunther (the boss’s wife), is sad and no longer fits in a society built on attraction and platitude. Brubaker catches her eye because he is unpolished. Even though he can be inept, he is genuine. She is convinced to give him a try when they spend a night in the company of a quirky couple, the Greenlaws, played by Myrna Loy and Charles Boyer, who live in a castle located somewhere in New York City. She tells fortunes. He practices fencing. They inspire Catherine to seek out a more enduring love. She chooses Brubaker.

Deneuve’s character, named Catherine Gunther (the boss’s wife), is sad and no longer fits in a society built on attraction and platitude. Brubaker catches her eye because he is unpolished. Even though he can be inept, he is genuine. She is convinced to give him a try when they spend a night in the company of a quirky couple, the Greenlaws, played by Myrna Loy and Charles Boyer, who live in a castle located somewhere in New York City. She tells fortunes. He practices fencing. They inspire Catherine to seek out a more enduring love. She chooses Brubaker. It should be noted that both Brubaker and Catherine are married. They leave their spouses, and the rest of their world’s behind. Ted Gunther is a smoothie who hits on other women and depends on his wife’s willingness to ignore his behavior. Sally Kellerman (an early heartthrob because of her part in a Star Trek episode) plays Brubaker’s wife Phyllis as distant and focused on her own projects. She talks at, not with, her husband and rushes off the phone to whatever actually holds her interest.

It should be noted that both Brubaker and Catherine are married. They leave their spouses, and the rest of their world’s behind. Ted Gunther is a smoothie who hits on other women and depends on his wife’s willingness to ignore his behavior. Sally Kellerman (an early heartthrob because of her part in a Star Trek episode) plays Brubaker’s wife Phyllis as distant and focused on her own projects. She talks at, not with, her husband and rushes off the phone to whatever actually holds her interest. All except for the magical Loy and Boyer, whose wealth does not stigmatize them so much as separate them from the herd. They spend the days asleep, because of all the bad things that happen in the sun. There is no explanation given for their presence, the same way that fairy godmothers have no explanation in fairy tales. I longed for quirky friends, even as a youth. My classmates talked about Happy Days and the Pittsburgh Pirates. I had other, more shadowy interests, and no one to share them with.

All except for the magical Loy and Boyer, whose wealth does not stigmatize them so much as separate them from the herd. They spend the days asleep, because of all the bad things that happen in the sun. There is no explanation given for their presence, the same way that fairy godmothers have no explanation in fairy tales. I longed for quirky friends, even as a youth. My classmates talked about Happy Days and the Pittsburgh Pirates. I had other, more shadowy interests, and no one to share them with. The April Fools implies that happiness derived from love is so rare that it will require a rule-breaking intercession to achieve it. What a strange foundation on which to build an idea of love, and at 14, that is what I was doing. And to think that a kiss ought to lead to a trip to Paris and a new life. How many kisses would come that did not bear that freight, that betrayed that wish?

The April Fools implies that happiness derived from love is so rare that it will require a rule-breaking intercession to achieve it. What a strange foundation on which to build an idea of love, and at 14, that is what I was doing. And to think that a kiss ought to lead to a trip to Paris and a new life. How many kisses would come that did not bear that freight, that betrayed that wish?

The Red Balloon to The Great Race, from The House of Frankenstein to The Trouble with Angels. I first saw Lawrence of Arabia on a 19-inch screen. I first watched the Wizard of Oz on a black and white television.

The Red Balloon to The Great Race, from The House of Frankenstein to The Trouble with Angels. I first saw Lawrence of Arabia on a 19-inch screen. I first watched the Wizard of Oz on a black and white television. Un Chien Andalou, and Birth of a Nation. Kaori Kitao used a projector to screen the films, and we watched and re-watched scenes for hours on Wednesday afternoons. Our three hour class often ran six hours.

Un Chien Andalou, and Birth of a Nation. Kaori Kitao used a projector to screen the films, and we watched and re-watched scenes for hours on Wednesday afternoons. Our three hour class often ran six hours. Mitchum, Rosalind Russell, Humphrey Bogart, Irene Dunne, Toshiro Mifune, Myrna Loy, Fred Astaire, and Charlie Chaplin.

Mitchum, Rosalind Russell, Humphrey Bogart, Irene Dunne, Toshiro Mifune, Myrna Loy, Fred Astaire, and Charlie Chaplin. My father loved movies. He shared his love of old horror movies with us, and we did watch Frankenstein and Godzilla together. Back then, Frankenstein was not played often on television, and one UHF channel featured a week of Toho giant monster films. These, along with the Wizard of Oz or Lawrence of Arabia, were event movies. I learned from watching movies that my father also had a soft spot, enjoying The Trouble with Angels and Agnes of God, but enjoying them alone and sharing his enjoyment after the fact. If I did not learn to watch movies alone from him, I certainly continued doing so, never feeling the need for company either when watching at home or in the theater.

My father loved movies. He shared his love of old horror movies with us, and we did watch Frankenstein and Godzilla together. Back then, Frankenstein was not played often on television, and one UHF channel featured a week of Toho giant monster films. These, along with the Wizard of Oz or Lawrence of Arabia, were event movies. I learned from watching movies that my father also had a soft spot, enjoying The Trouble with Angels and Agnes of God, but enjoying them alone and sharing his enjoyment after the fact. If I did not learn to watch movies alone from him, I certainly continued doing so, never feeling the need for company either when watching at home or in the theater. Are these the best depictions of love in the movies? Hardly. Nor are they the truest depictions. They simply stood out to me. Beyond that I had only two simple rules for their selection. First, I had to see each one first on television. All but one of these I watched alone the first time I saw it, with the exception being My Fair Lady, an event movie to be sure. Second I had to see each before I was 17, before I became an adult, and before I said the words “I love you” to a woman. Whether I like it or not, every time I have said those words, from the time I was 17 until now, when I am 57, “I love you” is an echo of something I saw in these films. For better and for worse.

Are these the best depictions of love in the movies? Hardly. Nor are they the truest depictions. They simply stood out to me. Beyond that I had only two simple rules for their selection. First, I had to see each one first on television. All but one of these I watched alone the first time I saw it, with the exception being My Fair Lady, an event movie to be sure. Second I had to see each before I was 17, before I became an adult, and before I said the words “I love you” to a woman. Whether I like it or not, every time I have said those words, from the time I was 17 until now, when I am 57, “I love you” is an echo of something I saw in these films. For better and for worse.