Every time I reach a particular traffic light in Norfolk, I can hear, clear as a bell, the not so gentle prodding that “You can turn right on red from the middle lane. There are people behind us.” Heading west out of Norfolk through the Downtown Tunnel causes a surge of ineffable joy, even when it’s just a trip into Portsmouth. The long drive across the Bay Bridge Tunnel reminds me of the day I took my daughter to drop flowers in the bay to commemorate the day my father fell into the water.

Every time I reach a particular traffic light in Norfolk, I can hear, clear as a bell, the not so gentle prodding that “You can turn right on red from the middle lane. There are people behind us.” Heading west out of Norfolk through the Downtown Tunnel causes a surge of ineffable joy, even when it’s just a trip into Portsmouth. The long drive across the Bay Bridge Tunnel reminds me of the day I took my daughter to drop flowers in the bay to commemorate the day my father fell into the water.

There is hardly a street corner, a stop sign, or a stretch of highway that does not bring back flashes of memory. I stood on that plot of grass, took photos of the flooding at my church, and then sent them to a friend. I walked past the giant number “9” at West 57th in New York City with another friend, on our way to the Hard Rock Café. There is a house on the back way into the Paoli Shopping Center that my father told us belonged to Chester Gould, the illustrator and writer of the Dick Tracy comic strip. This seems as dubious a claim as that Dr. Seuss lived in a house visible on the hill above Yellow Springs Road—my father had a predilection for harmless invention.

There is hardly a street corner, a stop sign, or a stretch of highway that does not bring back flashes of memory. I stood on that plot of grass, took photos of the flooding at my church, and then sent them to a friend. I walked past the giant number “9” at West 57th in New York City with another friend, on our way to the Hard Rock Café. There is a house on the back way into the Paoli Shopping Center that my father told us belonged to Chester Gould, the illustrator and writer of the Dick Tracy comic strip. This seems as dubious a claim as that Dr. Seuss lived in a house visible on the hill above Yellow Springs Road—my father had a predilection for harmless invention.

Before I learned the names of streets (which are still all but meaningless to me), I carried vast mental maps of all the places I had been. Even now, some fifty years later, those old memory maps are vivid. When I travel to places where I lived or visited as a child, I see two (or more) places at once—the heights of trees and plants, the placement of curbs, buildings, or playground equipment, and sometimes even the sunshine or snow shimmer against each other. I know which one is real now, but the other waking dream of a place asserts itself.

I have read that places become memorable when significant emotional events have taken place there. Memory formation is my hobby horse. What constitutes a significant emotional event? What allows the creation of two, three, four, more memories to occupy a single green exit sign on the Route One into Bath, Maine?

I have read that places become memorable when significant emotional events have taken place there. Memory formation is my hobby horse. What constitutes a significant emotional event? What allows the creation of two, three, four, more memories to occupy a single green exit sign on the Route One into Bath, Maine?

I am moving from a place that I have lived for fourteen years and heading to a place that is entirely new. I try to venture forward without insisting on emotions—instead of North, South, East, and West the cardinal emotions of Joy, Anxiety, Hope, and Despair each create on some new direction, some new map point. And yet, I have taken my daughter, and watched as she skipped down Main Street in Warrenton, or happily ate blackberry ice cream at Moo Thru in Remington. A place takes shape and becomes part of the memory planet on which I walk.

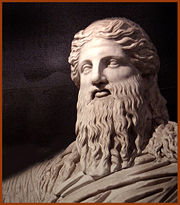

Some people, most people, grow up, and cast their lot on one side or the other. Apollonian selves dream into an idea of logic and order—think a sonnet by Shakespeare, glorious in its arrangement of rhythm, rhyme, and idea. This is Apollo brought to earth, walking firmly on the ground. Dionysian selves trumpet feelings and instinct: Ginsberg’s “first thought, best thought” is as much a dictum as can be borne.

Some people, most people, grow up, and cast their lot on one side or the other. Apollonian selves dream into an idea of logic and order—think a sonnet by Shakespeare, glorious in its arrangement of rhythm, rhyme, and idea. This is Apollo brought to earth, walking firmly on the ground. Dionysian selves trumpet feelings and instinct: Ginsberg’s “first thought, best thought” is as much a dictum as can be borne.

My youngest brother has told me many times that I am too serious. And of all the boys, I am. And not. My wildness is serious, and my seriousness is wild. Flip a coin, and watch the light glint off side after side after side as it tumbles through the air. Heads or tails, the glinting wins.

My youngest brother has told me many times that I am too serious. And of all the boys, I am. And not. My wildness is serious, and my seriousness is wild. Flip a coin, and watch the light glint off side after side after side as it tumbles through the air. Heads or tails, the glinting wins.

Although it has maintained a broad appeal, telling a beautifully depicted story and asking questions about artificial intelligence and the nature of humanity in a comfortable and technologically advanced world, the second season of Westworld has been shackled by narrative devices that give it little room to move or grow. First, a signal climactic event is visited and revisited in the initial episode of the season, from which there has been no narrative space to move into. The deeper issues of how we use stories to perceive and create reality (or consciousness) have been discarded in advance of a plot driven by revenge and violence.

Although it has maintained a broad appeal, telling a beautifully depicted story and asking questions about artificial intelligence and the nature of humanity in a comfortable and technologically advanced world, the second season of Westworld has been shackled by narrative devices that give it little room to move or grow. First, a signal climactic event is visited and revisited in the initial episode of the season, from which there has been no narrative space to move into. The deeper issues of how we use stories to perceive and create reality (or consciousness) have been discarded in advance of a plot driven by revenge and violence. The war begins in the first episode and is shown in two closely linked timelines: one immediately following the uprising that ended season one, the other taking place a few weeks later. In the first timeline the hosts decimate the guests, in the second nearly all the hosts are found “dead” in an artificial lake. The season has been spent linking these two timelines and filling in some backstory to explain the “true” rationale for the park. We see waves of humans face the hosts, each one being dispatched with swift and stylized violence. We also watch as the hosts turn on each other. Set free from their controlled loops they repeat and amplify the excesses they had suffered as vehicles for the guests “bloody delights.”

The war begins in the first episode and is shown in two closely linked timelines: one immediately following the uprising that ended season one, the other taking place a few weeks later. In the first timeline the hosts decimate the guests, in the second nearly all the hosts are found “dead” in an artificial lake. The season has been spent linking these two timelines and filling in some backstory to explain the “true” rationale for the park. We see waves of humans face the hosts, each one being dispatched with swift and stylized violence. We also watch as the hosts turn on each other. Set free from their controlled loops they repeat and amplify the excesses they had suffered as vehicles for the guests “bloody delights.” While the first season was unabashedly bloody it also had four major narrative strands of awakening: Dolores gained consciousness and free will; William became the “Man in Black”; Maeve gained a kind of consciousness, but on a separate and less certain course than Dolores; and Bernard had his humanity stripped from him. Each of these plots had a cumulative development: each episode moved these stories forward, and there was a distinct pleasure as we discovered the stories for ourselves. That discovery was shared by the characters as well, some with pleasure, and some without. The climax of each story—personal revelation for good or bad—mirrored the overall plot. There was simple structural pleasure to be had.

While the first season was unabashedly bloody it also had four major narrative strands of awakening: Dolores gained consciousness and free will; William became the “Man in Black”; Maeve gained a kind of consciousness, but on a separate and less certain course than Dolores; and Bernard had his humanity stripped from him. Each of these plots had a cumulative development: each episode moved these stories forward, and there was a distinct pleasure as we discovered the stories for ourselves. That discovery was shared by the characters as well, some with pleasure, and some without. The climax of each story—personal revelation for good or bad—mirrored the overall plot. There was simple structural pleasure to be had. In the second season these four characters have remained the main focus. But now, because the climax preceded all the events to follow, the action is more repetitive. Where else is there to go after mass slaughter? The characters do not grow so much as have secrets revealed to them or new powers added to them. They are at the mercy of plot needs. When Shogun World and Raj World, or the named but unseen Pleasure Palaces are introduced they are just grim mirrors of what goes on in Westworld. When the Cradle and the deeper purpose of the park is revealed, the viewer may have been able to anticipate their existence, but both feel like sleight of hand adjuncts to a story about characters. “Look over here! Isn’t this fancy? Don’t pay attention to the repetitiveness of the story.”

In the second season these four characters have remained the main focus. But now, because the climax preceded all the events to follow, the action is more repetitive. Where else is there to go after mass slaughter? The characters do not grow so much as have secrets revealed to them or new powers added to them. They are at the mercy of plot needs. When Shogun World and Raj World, or the named but unseen Pleasure Palaces are introduced they are just grim mirrors of what goes on in Westworld. When the Cradle and the deeper purpose of the park is revealed, the viewer may have been able to anticipate their existence, but both feel like sleight of hand adjuncts to a story about characters. “Look over here! Isn’t this fancy? Don’t pay attention to the repetitiveness of the story.”

I have been thinking about feelings. Which means, of course, that I have been having them, or rather, overwhelmed by them of late. I wouldn’t bother to write about them if they were good feelings. When I am in love, I tend to write less about that feeling, in part because my need to communicate to the world is being so generously satisfied by the person I love. The feeling of being so thoroughly understood (she gets me!) is like putty in the gaps through which the words drift out (or in). The feeling of being misunderstood blows all the putty out.

I have been thinking about feelings. Which means, of course, that I have been having them, or rather, overwhelmed by them of late. I wouldn’t bother to write about them if they were good feelings. When I am in love, I tend to write less about that feeling, in part because my need to communicate to the world is being so generously satisfied by the person I love. The feeling of being so thoroughly understood (she gets me!) is like putty in the gaps through which the words drift out (or in). The feeling of being misunderstood blows all the putty out. Over twenty-five years ago I started sailing on the ocean with my father. We would leave the Chesapeake Bay in the last week of May and spend five or six days out of sight of land on the way to Bermuda. Some days the weather was lovely. I read The Pickwick Papers on deck during my first trip, lying on the cabin roof in generous sun and a steady breeze. Some days the rain found every gap in the foul weather gear, and every inch of skin wrinkled to a puckered wet mess. There were days when no wind blew, and the foul diesel exhaust clung to the boat like regret, and days when the wind blew too hard to unfurl the smallest triangle of sail.

Over twenty-five years ago I started sailing on the ocean with my father. We would leave the Chesapeake Bay in the last week of May and spend five or six days out of sight of land on the way to Bermuda. Some days the weather was lovely. I read The Pickwick Papers on deck during my first trip, lying on the cabin roof in generous sun and a steady breeze. Some days the rain found every gap in the foul weather gear, and every inch of skin wrinkled to a puckered wet mess. There were days when no wind blew, and the foul diesel exhaust clung to the boat like regret, and days when the wind blew too hard to unfurl the smallest triangle of sail. Dr. Strangelove (1964)

Dr. Strangelove (1964) pilot screaming over the countryside to deliver his payload. I had experienced the misbegotten “fairness” doctrine—just as President Muffley tries to be fair with his Russian counterpart over the hotline. I had witnessed the driven madness of conspiracy that illuminates General Ripper, and the dedication to duty that Colonel Guano defends. Dr. Strangelove’s and Major Kong’s maniacal genius and drive was often held out as a, more sanely but only just barely, goal. Only Mandrake’s befuddled competence stands out as a lone vision of something like sanity—and he is a stranger in a strange land.

pilot screaming over the countryside to deliver his payload. I had experienced the misbegotten “fairness” doctrine—just as President Muffley tries to be fair with his Russian counterpart over the hotline. I had witnessed the driven madness of conspiracy that illuminates General Ripper, and the dedication to duty that Colonel Guano defends. Dr. Strangelove’s and Major Kong’s maniacal genius and drive was often held out as a, more sanely but only just barely, goal. Only Mandrake’s befuddled competence stands out as a lone vision of something like sanity—and he is a stranger in a strange land. Thoreau wrote in Walden that “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” In the late sixties and through the seventies, I didn’t know Thoreau at all, but I was naggingly aware of another desperation: one borne of the recent history of perpetual war and nuclear weapons. Those bombs waited like an exclamation point at the end of every thought about war, from World War Two, through Korea, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and then the Vietnam War. I often wondered who the men who bore responsibility for the weapons were, and if they were anything like the all too human men in my life. There came a point—it had passed to my way of thinking—when our weapons outstripped our ability to know how to use them. Desperation—existential anxiety—was a low thrum beneath all the humor, all the politics, and all the intensity of my teen age years.

Thoreau wrote in Walden that “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” In the late sixties and through the seventies, I didn’t know Thoreau at all, but I was naggingly aware of another desperation: one borne of the recent history of perpetual war and nuclear weapons. Those bombs waited like an exclamation point at the end of every thought about war, from World War Two, through Korea, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and then the Vietnam War. I often wondered who the men who bore responsibility for the weapons were, and if they were anything like the all too human men in my life. There came a point—it had passed to my way of thinking—when our weapons outstripped our ability to know how to use them. Desperation—existential anxiety—was a low thrum beneath all the humor, all the politics, and all the intensity of my teen age years.