I finished a first draft of a novel in the fall of 2019–a smidge past 88,000 words, huzzah! huzzah! I almost immediately began working on the next one. While at this new work, I managed a copywriter-style edit over the next year that swelled the thing by another 5,000 words, but other than adding connective tissue, it hadn’t substantially changed. I kept at the next book but felt a nagging unfinished feeling about the previous one that hindered my progress. Other events conspired (as they often do). An annoying fallow period set in when the twinned butterflies of ideas and scenes clashed until book #2 relented and declared, “Finish the other one and get back to me when you’re ready.”

It took about 15 painful minutes to realize I had arrived at the wrong ending. Actually, 15 glorious, freeing, soaring minutes, but then came the less soaring, freeing, and glorious realization that the hard work of revision waited. “Why not just change the ending?” you might ask. Because no matter how messy a novel is, with its few hundred threads strewn across the living room floor—some leading to the kitchen, some to the garage, and some impossibly outside through the dryer vent (can we not talk about those that lead down the WC, please?)—the line from beginning to end is the single thread that holds the vivid, continuous dream together.

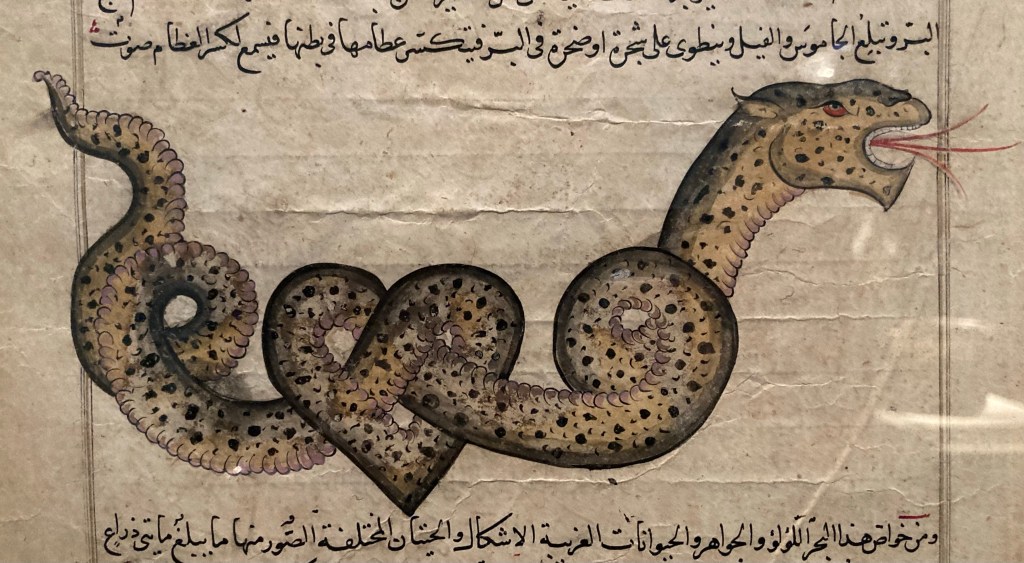

And so, revision. Fortunately, the events will remain (mostly) the same (that much I got right). Still, the permutations of characters and the thickets of motivations they brought with them to, say, a stone wall in Central Asia, changed. And so how characters walked, strode, strolled, marched, limped, ran, trudged, or galloped (one of the characters is a horse) to that wall also changed.

I know exactly why I ended the book as I had—a kind of brutally insistent wish fulfillment. And one of the nice things I realized is that the book had been fighting that resolution at its bones. So now it is throwing flowers at me as I realign characters (Oh, he said that–not her, and she said this instead—head smack—duh!), even though it demands new work and new consideration. I don’t know exactly how it all will come off, but it beckons with a willingness that is at once surprising and exacting. As I fall asleep, the book whispers, “You see this now, yes? So, do it.”

I will share a few of the changes as I proceed. I will try to explain why these changes occurred and what they mean in a general way. If this process only helped me with this one book and not in all the books to follow, what’s the point? We take the lessons as they come; I hope I’m not too obstinate to apply them. Others will surely follow.

There is no guarantee that these changes they will make it through to some “it’s out of my hands now” final draft. But I think much will.