At some point—and it happens fairly quickly—the life of an English teacher becomes more about re-reading than reading. This is a preposterous change from the life of a graduate student, when everything is reading. As a student, there may be a handful of books that one reads a twice, but those are also the books with which one spends an engaged period of time—there is an essay in the offing. If you read them twice, chances are you read them a half dozen or dozen times. By the time you start teaching, the repetition is no longer driven by your desire or directed curiosity, but by a curricular roadmap that more often than not, you have not decided.

At some point—and it happens fairly quickly—the life of an English teacher becomes more about re-reading than reading. This is a preposterous change from the life of a graduate student, when everything is reading. As a student, there may be a handful of books that one reads a twice, but those are also the books with which one spends an engaged period of time—there is an essay in the offing. If you read them twice, chances are you read them a half dozen or dozen times. By the time you start teaching, the repetition is no longer driven by your desire or directed curiosity, but by a curricular roadmap that more often than not, you have not decided.

Because of my background, my friends will often ask what I am reading, and I know that they mean, “What are you reading for the first time?” It’s a “tell me what is good” question. At this moment in my life, most of what I read, I am reading for the 7th or 8th time. Or I am reading student work. I can admit that neither fills my sails the same way that exploratory reading does. Part of the joy of exploring is not reading important books—or rather, it is discovering that the books I read were important (to me, to the world) as I read them.

There is something thrilling—yes, thrilling—in finding myself in an entirely new stream of thought, full of images and ideas that had not occurred in my mind in that specific way. I love the feeling of being in an entirely foreign mind. I brought home new avenues and new approaches to my own work from nearly every book I read as a student. And, yes, I am still a student, and I still find new ways. Early on, the novelty that most easily enchanted me was setting and plot. Novels set in strange places (Vietnam, Middle Earth, Geatland, London) and with characters who did strange things (solve crimes, fly dragons, uncover moles, turn into monsters) drew my attention and appreciation. I still appreciate a mystery, horror, or fantasy novel; Michael Chabon tethers genre to literary merit with alacrity.

But most works of literary merit tend to eschew genre elements. The strangeness is found more in how the characters think and feel, and how those thoughts and feeling serve to reveal the deeper ideas that the novel walks out into the world. The thrill comes from reading along as characters struggle with complex thoughts and feelings, and the novelist struggles to portray a world that is, more often than not, contradictory. Contradiction is the single provenance of literary fiction. Woe to the mind and heart that seeks a generously reductive answer to life’s troubles in literature. Unless one learns to love ambiguity, irony, and contradiction.

I think that the rush of all the new work I read while I was still a full time student, blunted the more mournful aspects of contradiction. As I read through libraries, it seemed as if there were a million ways to get things done. I continue to champion diversity in large part because I found comfort in the breadth of possibility. However, the habits of re-reading drive me to emphasize less possibility. This occurs because if contradiction is the provenance of literature, then what happens in the land of contradiction is too often sad. Characters are too often caught, like Odysseus, between Scylla and Charybdis—the chance of losing everything and the certainty of losing much. Where is the gain—other than hard-earned self-knowledge? Where is the dinner and conversation and new-forged friendship with people who had been, only moments ago, strangers?

I feel the loss keenly. I am dissatisfied with the too morbid outcomes that serious writers propose, and with the deathly insistence on disconnection and disappointment. And I am dissatisfied with trudging over this same ground over and over again. There must be the possibility of joy, and please, for gods’ sakes, there must be discovery. Which means new works. In “Seymour: An Introduction,” Salinger allows Seymour to give his brother, Bruno, the single best piece of writing advice—and by extension, life advice—I have ever read. It is hopeful. “Imagine the book you most want to read… Now write it.”

I feel the loss keenly. I am dissatisfied with the too morbid outcomes that serious writers propose, and with the deathly insistence on disconnection and disappointment. And I am dissatisfied with trudging over this same ground over and over again. There must be the possibility of joy, and please, for gods’ sakes, there must be discovery. Which means new works. In “Seymour: An Introduction,” Salinger allows Seymour to give his brother, Bruno, the single best piece of writing advice—and by extension, life advice—I have ever read. It is hopeful. “Imagine the book you most want to read… Now write it.”

It is time. Finally.

When I sit down to write, I haven’t thought about an audience. Often I feel more like an amanuensis, copying down whatever the universe commands. The universe commands much, by the way. You might call it inspiration—divine or otherwise. I have not spent much time trying to figure out “my voice,” as much as I have trying to listen keenly to what comes my way.

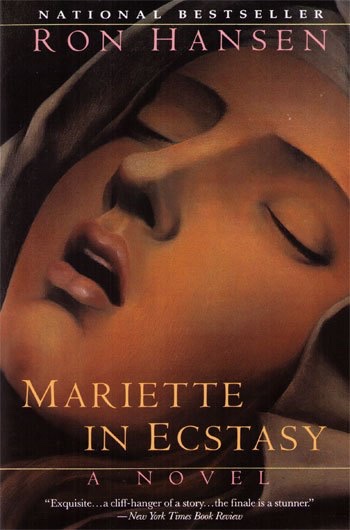

When I sit down to write, I haven’t thought about an audience. Often I feel more like an amanuensis, copying down whatever the universe commands. The universe commands much, by the way. You might call it inspiration—divine or otherwise. I have not spent much time trying to figure out “my voice,” as much as I have trying to listen keenly to what comes my way. One of my first teachers, Ron Hansen, ends his spectacular novel Mariette in Ecstasy with Mariette’s message from her muse (who just happens to be God). The message is, “Surprise me.” I read that years and years ago, and only now has the lesson begun to take hold. How I wish I had stumbled into that realization 20 years ago. But better now, late as it is, than not at all.

One of my first teachers, Ron Hansen, ends his spectacular novel Mariette in Ecstasy with Mariette’s message from her muse (who just happens to be God). The message is, “Surprise me.” I read that years and years ago, and only now has the lesson begun to take hold. How I wish I had stumbled into that realization 20 years ago. But better now, late as it is, than not at all.

In between units of my AP English class, I spent a few days with William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience. Blake doesn’t fit nicely into any tradition of British Literature, but his work touches on some of the realities of life in London that other writers ignore. So before we charge into Jane Eyre, Blake.

In between units of my AP English class, I spent a few days with William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience. Blake doesn’t fit nicely into any tradition of British Literature, but his work touches on some of the realities of life in London that other writers ignore. So before we charge into Jane Eyre, Blake. I have a confession. I have a terrible time receiving love. I’m sure that this is true of almost everyone, so, I’m reluctant to make any big claim about it.

I have a confession. I have a terrible time receiving love. I’m sure that this is true of almost everyone, so, I’m reluctant to make any big claim about it.

It is the same with writing. I have used this blog as practice off and on for the past few years. It has been a way to scribble and not to worry about the duration of longer effort. Longer effort—let me call it what it is, a novel—can be daunting. What if, like falling and flying, one mistimes the creative leap and ends up hobbled or broken, with months of work sent to sea like Icarus? I only I can think about something longer as, well, 1000 word spans. 1000 words is nothing. 60 days at that pace, and… But let’s not get ahead.

It is the same with writing. I have used this blog as practice off and on for the past few years. It has been a way to scribble and not to worry about the duration of longer effort. Longer effort—let me call it what it is, a novel—can be daunting. What if, like falling and flying, one mistimes the creative leap and ends up hobbled or broken, with months of work sent to sea like Icarus? I only I can think about something longer as, well, 1000 word spans. 1000 words is nothing. 60 days at that pace, and… But let’s not get ahead. I take refuge in Michelangelo’s vision of the sculpture already extant in the stone—we aren’t creators so much as revealers—discoverers if you will. So too, with flight, while there may be a destination, there are also loops and rolls and fields long enough to land, and walk to an untended apple tree, pick a ripe crisp fruit, and eat. Discover this on the journey.

I take refuge in Michelangelo’s vision of the sculpture already extant in the stone—we aren’t creators so much as revealers—discoverers if you will. So too, with flight, while there may be a destination, there are also loops and rolls and fields long enough to land, and walk to an untended apple tree, pick a ripe crisp fruit, and eat. Discover this on the journey. “What do I have to say?”

“What do I have to say?”