Play it loud.

Play it loud.

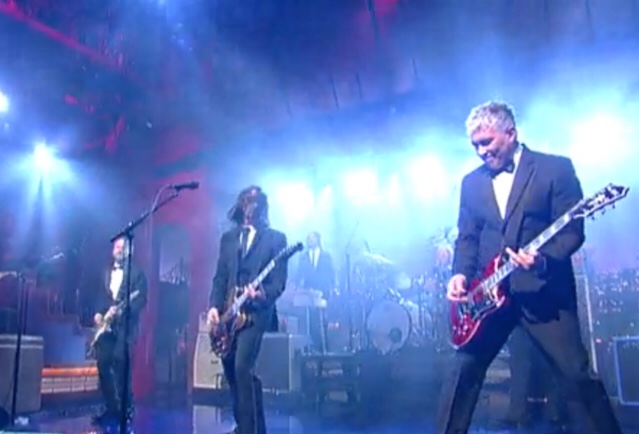

On May 20, 2015, Letterman’s last show ended with the Foo Fighters ripping into an extended version of “Everlong” while a montage of Letterman’s thirty-three years on television played.

And I wonder

When I sing along with you

If everything could ever be this real forever

If anything could ever be this good again

The guitars churn through the song, tearing as deeply into sadness and desire as can be imagined. It struck every chord with me then. Something was gone, but something was good. And loud—and it built, simple layer on simple layer.

Later that summer, I listened to the song in my car before work, before everyone arrived, and the minister for that Sunday (we had a different minister nearly every Sunday in the year of the aftermath of Jenifer Slade’s suicide) pulled into the space next to mine. When I explained the context of the song—briefly—her response was, “My son used to listen to them. I don’t like the Foo Fighters.” Several years afterwards, her name was floated as a possible minister for our church—I cringed.

I like to play music loud—scratch that, I love it loud. My rear view mirror vibrates along to the beat. I love to sing along until my voice is raspy (vocal fry be damned). Springsteen, Foo Fighters, The Pixies, Liz Phair, Aimee Mann (who doesn’t rip it up, but…), U2, Arcade Fire, David Bowie, PJ Harvey. There are others. My Bloody Valentine rang in my ears while seas chased my boat on the ocean.

This has been true for ages. When my coworkers drank their way out of a dinner shift, I got in my car and drove. Turning up the sound until my little Volkswagen caught the turns of country roads to swelling arpeggios. No DUI, just driving while loud. When I swim, I play music loud enough and vicious enough to make the pain in my arms and legs seem like an afterthought. It’s fuel, pure and simple. Fuel with a taskmaster’s beat.

Less never really captivates me. I can appreciate quiet and simplicity, but if I’m going to be transported—physically, spiritually, even mentally—I must crank it up. These days I don’t crack the sound barrier, and the music does not make me forget the limits—not the sensible ones. Still, it opens a gap, a crack in the hard stupid shell of “I don’t like…”

I was at a show for the band The Snails a couple of years ago—proto-punk silliness (they came out with trash bags full of balloons on their backs—like snails!). Everyone kept the beat, even this old man, especially this old man.

The only thing I’ll ever ask of you

Got to promise not to stop when I say “When”

Play it loud.

I started watching comedians late at night with my father, who was a Carson devotee. My dad would take a nap after dinner—short, maybe 20 minutes in his chair in the den—before watching television or reading until the news and then the Tonight Show. He would stay up until Carson finished at 1 am (later only until 12:30 am). My mother absented the scene well before 11.

I started watching comedians late at night with my father, who was a Carson devotee. My dad would take a nap after dinner—short, maybe 20 minutes in his chair in the den—before watching television or reading until the news and then the Tonight Show. He would stay up until Carson finished at 1 am (later only until 12:30 am). My mother absented the scene well before 11. In 1982, the year I graduated from college, Letterman took over what had been a fairly straight talk show slot. Tom Snyder’s Tomorrow had ended NBC’s programming. Snyder was as hip as could be imagined at the time, smoking a cigarette and asking pointedly bemused questions. Letterman rolled in on a wave of calculated whimsy and sarcasm. He was a genial wiseass—smart enough to host Fran Leibovitz, foolish enough to wear a suit of Alka-seltzer tablets into a dunk tank. While Carson chuckled at the world, Letterman was in perpetual eye roll. “These people are idiots,” he seemed to say, “And if we aren’t careful, we are too.”

In 1982, the year I graduated from college, Letterman took over what had been a fairly straight talk show slot. Tom Snyder’s Tomorrow had ended NBC’s programming. Snyder was as hip as could be imagined at the time, smoking a cigarette and asking pointedly bemused questions. Letterman rolled in on a wave of calculated whimsy and sarcasm. He was a genial wiseass—smart enough to host Fran Leibovitz, foolish enough to wear a suit of Alka-seltzer tablets into a dunk tank. While Carson chuckled at the world, Letterman was in perpetual eye roll. “These people are idiots,” he seemed to say, “And if we aren’t careful, we are too.” When he left in 2015, it marked the end of my Second, and maybe Third Act. From graduation from Swarthmore to graduate school at Binghamton, from adjunct teaching to secondary ed teaching, from occasional church goer to religious professional, from single, to committed cohabitation, to marriage, and finally to separation and divorce. I still watch late night comedians, but now they function almost only as an antidote to the news. Please, someone make light of the daily made-up facts. Maybe that will end when the current administration leaves, and maybe a sequel to Ionesco’s Rhinoceros will have everyone gleefully turning back into humans.

When he left in 2015, it marked the end of my Second, and maybe Third Act. From graduation from Swarthmore to graduate school at Binghamton, from adjunct teaching to secondary ed teaching, from occasional church goer to religious professional, from single, to committed cohabitation, to marriage, and finally to separation and divorce. I still watch late night comedians, but now they function almost only as an antidote to the news. Please, someone make light of the daily made-up facts. Maybe that will end when the current administration leaves, and maybe a sequel to Ionesco’s Rhinoceros will have everyone gleefully turning back into humans. When I was 11, I started sailing with my father. We took lessons together and practiced on a lake. He kept a boat on the Chesapeake Bay, which was rarely choppy. In my thirties, I joined him on the ocean—home again.

When I was 11, I started sailing with my father. We took lessons together and practiced on a lake. He kept a boat on the Chesapeake Bay, which was rarely choppy. In my thirties, I joined him on the ocean—home again. Deep time? Not thousands of years—a blink. Millions begin to register. Billions of years. I once had my students hold one hundred feet of rope, and marked the history of the planet on it. Those who held on to human historical events: Lucy, the Pyramids, the Great Wall of China, the Renaissance, man walking on the moon—could barely wrap a finger around the rope they were crowded so close. Our Western Mountains—the Rockies—and Eastern Mountains—were flung apart, but well after our continent had formed.

Deep time? Not thousands of years—a blink. Millions begin to register. Billions of years. I once had my students hold one hundred feet of rope, and marked the history of the planet on it. Those who held on to human historical events: Lucy, the Pyramids, the Great Wall of China, the Renaissance, man walking on the moon—could barely wrap a finger around the rope they were crowded so close. Our Western Mountains—the Rockies—and Eastern Mountains—were flung apart, but well after our continent had formed. Where does sadness, the inexorable seriousness in my writing originate? My friends would tell you that I am puckish in real life—if anything, a bit too unrestrained. Why doesn’t that same sense of things stripe my writing? Why do I seem stuck hitting the same damn dour note?

Where does sadness, the inexorable seriousness in my writing originate? My friends would tell you that I am puckish in real life—if anything, a bit too unrestrained. Why doesn’t that same sense of things stripe my writing? Why do I seem stuck hitting the same damn dour note? I packed my suitcase and drove out of Philadelphia. Whether that was yesterday or twenty-five years ago, I am not sure. There is so much to do, so many cities to visit, all those people waiting. I lose track of time. Before I have barely begun, I am completely exhausted. I have to stop. I ask the manager at the motor hotel for a quiet room, and flop into bed. I set the alarm clock for morning.

I packed my suitcase and drove out of Philadelphia. Whether that was yesterday or twenty-five years ago, I am not sure. There is so much to do, so many cities to visit, all those people waiting. I lose track of time. Before I have barely begun, I am completely exhausted. I have to stop. I ask the manager at the motor hotel for a quiet room, and flop into bed. I set the alarm clock for morning. And yet we build, and not every tool—Kubrick’s 2001 aside—is a refinement of a club. Certainly Kubrick’s 2001 won’t help one win a war, or woo, unless, of course, the object of desire is imbued with an essential and unmitigated nerdiness. Nonetheless, even without some mysterious aid, we grow. Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but soon enough, and we find our way to each other.

And yet we build, and not every tool—Kubrick’s 2001 aside—is a refinement of a club. Certainly Kubrick’s 2001 won’t help one win a war, or woo, unless, of course, the object of desire is imbued with an essential and unmitigated nerdiness. Nonetheless, even without some mysterious aid, we grow. Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but soon enough, and we find our way to each other. I recently swapped the nicknames that we give our kids with a friend. We had both, surprisingly and strangely, settled on “Bug.” I’m not sure that our daughters will appreciate that longer into their lives, but for now, it will do.

I recently swapped the nicknames that we give our kids with a friend. We had both, surprisingly and strangely, settled on “Bug.” I’m not sure that our daughters will appreciate that longer into their lives, but for now, it will do. And I do know the other side. I know how easy it is to let upset slide into hate. And I know that once uttered—by an adult, not by a child, because children must experiment with all words and all emotions—it breaks the bonds in a nearly irrevocable way. I have said it, out loud—either in the perpetual external conversation I have with the world or directly the object of scorn—and the immediate thrill is followed by a deep remorse as the tendrils that connected me to another person wither immediately into dried spiked vines, like the hedges of multiflora rosa that grew brown and foreboding in winter. All that was planted must be uprooted. Maybe something can be saved, some sprig, somewhere.

And I do know the other side. I know how easy it is to let upset slide into hate. And I know that once uttered—by an adult, not by a child, because children must experiment with all words and all emotions—it breaks the bonds in a nearly irrevocable way. I have said it, out loud—either in the perpetual external conversation I have with the world or directly the object of scorn—and the immediate thrill is followed by a deep remorse as the tendrils that connected me to another person wither immediately into dried spiked vines, like the hedges of multiflora rosa that grew brown and foreboding in winter. All that was planted must be uprooted. Maybe something can be saved, some sprig, somewhere. I wrote this years and years ago. Later, I sat down on a stone wall in a tony neighborhood in Baltimore to wait for a bus, thinking about nothing other than the weather—it was a late spring, the sky was all but cloudless—when I realized that the stones were swarming with ants. I quickly stood up, and brushed many, too many, off my pants. I knew what I had done. I laughed, and started walking.

I wrote this years and years ago. Later, I sat down on a stone wall in a tony neighborhood in Baltimore to wait for a bus, thinking about nothing other than the weather—it was a late spring, the sky was all but cloudless—when I realized that the stones were swarming with ants. I quickly stood up, and brushed many, too many, off my pants. I knew what I had done. I laughed, and started walking. I am unpacking and repacking old boxes. I have no fantasy that I will throw away old essays or my notes from Joyce and Woolf classes. But there are things I threw into boxes as deadlines approached, and now, when I look at them, nothing. I have whole boxes of emotional and intellectual cul de sacs.

I am unpacking and repacking old boxes. I have no fantasy that I will throw away old essays or my notes from Joyce and Woolf classes. But there are things I threw into boxes as deadlines approached, and now, when I look at them, nothing. I have whole boxes of emotional and intellectual cul de sacs.