I begin easily enough. Before I know it, a length has passed in the pool—most of it underwater as I dolphin kick on my back until the flags at the far end of the pool pass over my head. Or a new job begins, with all the attendant paperwork and the meetings with people who think they know my job better than I do. They know something better, and I try to learn, as quickly as possible. Or a new romance, which is like falling, and is as easy as falling, the way falling is entirely effortless. What comes next?

The grind of workout #89, when the music on the waterproof MP3 player fails to inspire a quickened pace, and the bottom of the pool is endless. Or the month after the initial set of grades are due, and the fourth set of essays come across my desk. Not again. Not the same mess of misspellings and three page paragraphs. Or when the obligations of work and family eat into the blissful times, and bliss becomes quotidian. Imagine that, quotidian bliss.

In every aspect of my life, the transition from beginning to middle happens almost by accident. Like tripping over a carpet. I get used to the puckered places on the floor—or tug the whole thing up, and set it back down again, flat, until the gremlins shift it around again. And then I tug it up again. And again. One time will not do. One run of the vacuum. One load of laundry. Another set of tests to grade. Another and another and another.

But some things bear repetition, even improve. Like love. While it is hard to make the transition from falling to landing, it is better still to learn to fly, to find the joy. The old joke about, I just flew in from Los Angeles, and boy, are my arms tired. I would live for my arms to be so tired with the effort of flight. And it would be worth the effort, each fluctuation of my unseen wings, soaring in unison with my love.

It is the same with writing. I have used this blog as practice off and on for the past few years. It has been a way to scribble and not to worry about the duration of longer effort. Longer effort—let me call it what it is, a novel—can be daunting. What if, like falling and flying, one mistimes the creative leap and ends up hobbled or broken, with months of work sent to sea like Icarus? I only I can think about something longer as, well, 1000 word spans. 1000 words is nothing. 60 days at that pace, and… But let’s not get ahead.

It is the same with writing. I have used this blog as practice off and on for the past few years. It has been a way to scribble and not to worry about the duration of longer effort. Longer effort—let me call it what it is, a novel—can be daunting. What if, like falling and flying, one mistimes the creative leap and ends up hobbled or broken, with months of work sent to sea like Icarus? I only I can think about something longer as, well, 1000 word spans. 1000 words is nothing. 60 days at that pace, and… But let’s not get ahead.

Is writing something longer romantic? For me, yes. I have fallen out of love with several novels that I have begun. The ideas and characters have soured, or I have not loved them well enough to let them live beyond my narrow conception of them. For me, as much as writing is a commitment of ass to chair (scribble, scribble, Dr. Brennan), it mimics the action of reading—a generous engagement with a book. Seymour Glass’s best piece of writing advice ever— “Imagine the book you most want to read. Now go and write it”—has always resonated with me. And until now, other than some shorter pieces, no longer piece has fully met that criteria. Or, I was not up to the flight.

In the end, really, I don’t write because I have something to say, but still, because I want to discover something. Before I was a writer, I was a reader, and I still love to read. The same way that I love to travel, I love to discover ideas and characters in books. It is flight into unknown places. I love discovering what I do not know. Somewhere along the way the creative process seduces one into intention—I get caught in the web of intention—thinking about what I want to say instead of praising what I see. And letting my words find a way.

I take refuge in Michelangelo’s vision of the sculpture already extant in the stone—we aren’t creators so much as revealers—discoverers if you will. So too, with flight, while there may be a destination, there are also loops and rolls and fields long enough to land, and walk to an untended apple tree, pick a ripe crisp fruit, and eat. Discover this on the journey.

I take refuge in Michelangelo’s vision of the sculpture already extant in the stone—we aren’t creators so much as revealers—discoverers if you will. So too, with flight, while there may be a destination, there are also loops and rolls and fields long enough to land, and walk to an untended apple tree, pick a ripe crisp fruit, and eat. Discover this on the journey.

How many other aspects of my life follow this impulse—reveling in discovery more than intentional design? I think too many. Most people still live their lives primarily by design. There is security and satisfaction in the sense of agency that willfulness bestows. My students clamor to know what they need to do to earn an “A,” or a higher score on an exam. How unsatisfyingly do I answer, “Discover more.” That is no way forward, at least no specific way. It is an attitude and not a route.

And frankly, in romance, I have scuttled relationships because I have fought against others’ plans, not happy to simply follow the natural stages of things, and unhappy when a relationship settled into a routine. Of course, life is routine, a series of repeated rituals, a hundred thousand undulations of wings. But that routine, those rituals, can, should, must help one reveal what is hidden in the marble, or what might be found when gloriously in flight.

Perhaps, what I wanted, without knowing it, was someone who was willing to fly with me. And in my writing, something that had the chance of slipping the bonds of my intentions. A goal I could fly toward, that would transport me the same way that love transports and transforms me.

There is a little secret though. I do have at least one intention, and that is for this longer work to last, for it to remain engaging and vital, even when the effort strains my arms. And so, I take small flights. And share these flights, for now, with one who flies with me. I discover something new, one winged trip at a time.

When I sit down to write, I haven’t thought about an audience. Often I feel more like an amanuensis, copying down whatever the universe commands. The universe commands much, by the way. You might call it inspiration—divine or otherwise. I have not spent much time trying to figure out “my voice,” as much as I have trying to listen keenly to what comes my way.

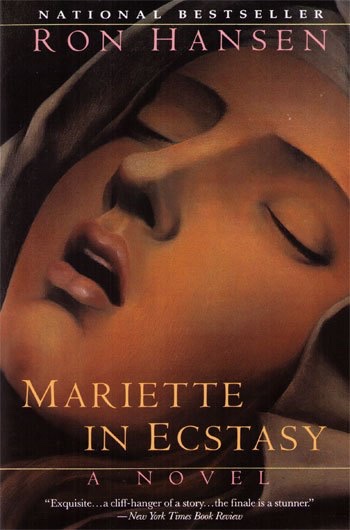

When I sit down to write, I haven’t thought about an audience. Often I feel more like an amanuensis, copying down whatever the universe commands. The universe commands much, by the way. You might call it inspiration—divine or otherwise. I have not spent much time trying to figure out “my voice,” as much as I have trying to listen keenly to what comes my way. One of my first teachers, Ron Hansen, ends his spectacular novel Mariette in Ecstasy with Mariette’s message from her muse (who just happens to be God). The message is, “Surprise me.” I read that years and years ago, and only now has the lesson begun to take hold. How I wish I had stumbled into that realization 20 years ago. But better now, late as it is, than not at all.

One of my first teachers, Ron Hansen, ends his spectacular novel Mariette in Ecstasy with Mariette’s message from her muse (who just happens to be God). The message is, “Surprise me.” I read that years and years ago, and only now has the lesson begun to take hold. How I wish I had stumbled into that realization 20 years ago. But better now, late as it is, than not at all.

In between units of my AP English class, I spent a few days with William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience. Blake doesn’t fit nicely into any tradition of British Literature, but his work touches on some of the realities of life in London that other writers ignore. So before we charge into Jane Eyre, Blake.

In between units of my AP English class, I spent a few days with William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience. Blake doesn’t fit nicely into any tradition of British Literature, but his work touches on some of the realities of life in London that other writers ignore. So before we charge into Jane Eyre, Blake. In many ways, I take solace in being surrounded by memories, and there are some that I purposefully mine. The routine of the same lunch—on most days—reminds me of years of similar lunches from the time I was five—earlier—until just last week—and all the lunches in between. I feel comforted by the way those memories permeate my present so easily.

In many ways, I take solace in being surrounded by memories, and there are some that I purposefully mine. The routine of the same lunch—on most days—reminds me of years of similar lunches from the time I was five—earlier—until just last week—and all the lunches in between. I feel comforted by the way those memories permeate my present so easily. I have written about the powerful memories associated with places—a rolling set of hills on a road headed north, an intersection with two right turn lanes, a road sign, the curve of a shoreline, a buoy. But, it is everything else as well. All the things. My walls at home are lined with books, and the books speak—not just of what is contained in their pages, but of the times I read them, the places I was, the company that surrounded those moments. And there is more, a gesture, my hand on a doorknob, the sudden turn of my head when I look for something, the way my foot falls on a stair. I am out of myself in a flash, or at least out of this time—even though I know that I am inextricably in it—and another older time surges through me. Even when still, this heartbeat explodes into a thousand, a million other heartbeats, and time collapses.

I have written about the powerful memories associated with places—a rolling set of hills on a road headed north, an intersection with two right turn lanes, a road sign, the curve of a shoreline, a buoy. But, it is everything else as well. All the things. My walls at home are lined with books, and the books speak—not just of what is contained in their pages, but of the times I read them, the places I was, the company that surrounded those moments. And there is more, a gesture, my hand on a doorknob, the sudden turn of my head when I look for something, the way my foot falls on a stair. I am out of myself in a flash, or at least out of this time—even though I know that I am inextricably in it—and another older time surges through me. Even when still, this heartbeat explodes into a thousand, a million other heartbeats, and time collapses. And so, beside my own strange face, I also take pleasure in crowds of strange faces, all of whom present unknown avenues, untapped sources of experiences and memories. I know the echoes will come to the strange person I will again be tomorrow.

And so, beside my own strange face, I also take pleasure in crowds of strange faces, all of whom present unknown avenues, untapped sources of experiences and memories. I know the echoes will come to the strange person I will again be tomorrow.

I have a confession. I have a terrible time receiving love. I’m sure that this is true of almost everyone, so, I’m reluctant to make any big claim about it.

I have a confession. I have a terrible time receiving love. I’m sure that this is true of almost everyone, so, I’m reluctant to make any big claim about it.

It is the same with writing. I have used this blog as practice off and on for the past few years. It has been a way to scribble and not to worry about the duration of longer effort. Longer effort—let me call it what it is, a novel—can be daunting. What if, like falling and flying, one mistimes the creative leap and ends up hobbled or broken, with months of work sent to sea like Icarus? I only I can think about something longer as, well, 1000 word spans. 1000 words is nothing. 60 days at that pace, and… But let’s not get ahead.

It is the same with writing. I have used this blog as practice off and on for the past few years. It has been a way to scribble and not to worry about the duration of longer effort. Longer effort—let me call it what it is, a novel—can be daunting. What if, like falling and flying, one mistimes the creative leap and ends up hobbled or broken, with months of work sent to sea like Icarus? I only I can think about something longer as, well, 1000 word spans. 1000 words is nothing. 60 days at that pace, and… But let’s not get ahead. I take refuge in Michelangelo’s vision of the sculpture already extant in the stone—we aren’t creators so much as revealers—discoverers if you will. So too, with flight, while there may be a destination, there are also loops and rolls and fields long enough to land, and walk to an untended apple tree, pick a ripe crisp fruit, and eat. Discover this on the journey.

I take refuge in Michelangelo’s vision of the sculpture already extant in the stone—we aren’t creators so much as revealers—discoverers if you will. So too, with flight, while there may be a destination, there are also loops and rolls and fields long enough to land, and walk to an untended apple tree, pick a ripe crisp fruit, and eat. Discover this on the journey. “What do I have to say?”

“What do I have to say?”

I do not know Bret Kavanaugh, nor do I have any idea what Georgetown Prep, his high school, was like.

I do not know Bret Kavanaugh, nor do I have any idea what Georgetown Prep, his high school, was like.